If we want to avoid the kind of Greek-style fiscal collapse implied by this BIS and OECD data, we need some external force to limit the tendency of politicians to over-tax and over-spend.

That’s why I’m a big advocate of tax competition, fiscal sovereignty, and financial privacy (read Pierre Bessard and Allister Heath to understand why these issues are critical).

Simply stated, I want people to have the freedom to benefit from better tax policy in other jurisdictions, especially since that penalizes governments that get too greedy.

I’m currently surrounded by hundreds of people who share my views since I’m in Prague at a meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society. And I’m particularly happy since Professor Lars Feld of the University of Freiburg presented a paper yesterday on “Redistribution through public budgets: Who pays, who receives, and what effects do political institutions have?”.

His research produced all sorts of interesting results, but I was drawn to his estimates on how tax competition and fiscal decentralization are an effective means of restraining bad fiscal policy.

Here are some findings from the study, which was co-authored with Jan Schnellenbach of the University of Heidelberg.

In line with the previous subsections, we find that countries with a higher GDP per employee, i.e. a higher overall labor productivity, have a more unequal primary income distribution. …fiscal competition within a country or trade openness as an indicator of globalization do not exacerbate, but reduce the gap between income classes. …expenditure and revenue decentralization restrict the government’s ability to redistribute income when fiscal decentralization also involves fiscal competition. …fiscal decentralization, when accompanied by high fiscal autonomy, involves significantly less fiscal redistribution. Please also note that fiscal competition induces a more equal distribution of primary income and, even though the distribution of disposable income is more unequal, it is open how the effect of fiscal competition on income distribution should be evaluated. Because measures of income redistribution usu-ally have adverse incentive effects which consequently affect economic growth negatively, fiscal competition might be favorable for countries which have strong egalitarian preferences. A rising tide lifts all boats and might in the long-run outperform countries with more moderate income redistribution even in distributional terms.

The paper includes a bunch of empirical results that are too arcane to reproduce here, but they basically show that the welfare state is difficult to maintain if taxpayers have the ability to vote with their feet.

Or perhaps the better way to interpret the data is that fiscal competition makes it difficult for governments to expand the welfare state to dangerous levels. In other words, it is a way of protecting governments from the worst impulses of their politicians.

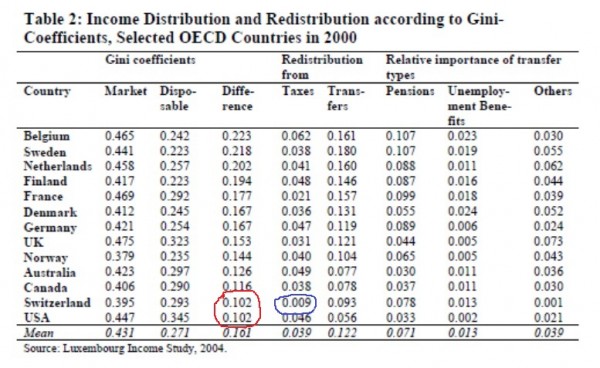

I can’t resist sharing one additional bit of information from the Feld-Schnellenbach paper. They compare redistribution in several nations. As you can see in the table reproduced below, the United States and Switzerland benefit from having the lowest levels of overall redistribution (circled in red).

It’s no coincidence that the U.S. and Switzerland are also the two nations with the most decentralization (some argue that Canada may be more decentralized that the U.S., but Canada also scores very well in this measure, so the point is strong regardless).

Interestingly, Switzerland definitely has significantly more genuine federalism than any other nation, so you won’t be surprised to see that Switzerland is far and away the nation with the lowest level of tax redistribution (circled in blue).

One clear example of Switzerland’s sensible approach is that voters overwhelmingly rejected a 2010 referendum that would have imposed a minimum federal tax rate of 22 percent on incomes above 250,000 Swiss Francs (about $262,000 U.S. dollars). And the Swiss also have a spending cap that has reduced the burden of government spending while most other nations have moved in the wrong direction.

One clear example of Switzerland’s sensible approach is that voters overwhelmingly rejected a 2010 referendum that would have imposed a minimum federal tax rate of 22 percent on incomes above 250,000 Swiss Francs (about $262,000 U.S. dollars). And the Swiss also have a spending cap that has reduced the burden of government spending while most other nations have moved in the wrong direction.

While there are some things about Switzerland I don’t like, its political institutions are a good role model. And since good institutions promote good policy (one of the hypotheses in the Feld-Schnellenbach paper) and good policy leads to more prosperity, you won’t be surprised to learn that Swiss living standards now exceed those in the United States. And they’re the highest-ranked nation in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report.