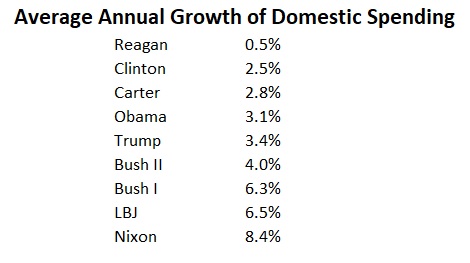

In 2020, I crunched numbers from OMB’s Historical Tables to rank the fiscal performance of nine recent presidents, going all the way back to LBJ.

I was especially interested to see which presidents did best and worst when looking on overall domestic spending (entitlements plus discretionary).

The numbers showed that Ronald Reagan easily was the most fiscally prudent while Richard Nixon was the worst of the worst (though there’s an argument that LBJ was even worse when looking at the long-run impact of his policies).

So it’s no surprise that I consider myself a Reaganite.

That being said, that chart actually understates Reagan’s success. As I wrote last year, it “doesn’t even fully capture what he achieved since he was able to rescind some of the spending in Jimmy Carter’s last fiscal year.”

Time to rectify that oversight and we’ll base today’s analysis on a report from the Government Accountability Office. According to GAO, Reagan proposed to rescind more than $15 billion of spending in 1981 and Congress agreed to rescind nearly $10.9 billion.

So what happens if we update the budget rankings to capture this additional fiscal restraint? As you can see, Reagan’s remarkable record gets even better compared to the numbers I prepared in 2020 and Jimmy Carter’s so-so performance deteriorates.

To put Reagan’s rescission in context, a $10.9 billion cut was equal to more than 7 percent of total domestic discretionary spending in Jimmy Carter’s last fiscal year.

Doing the same thing today would require a rescission of more than $70 billion.

I also calculated back in 2011 that Reagan reduced domestic spending by 2.5 percentage points of GDP. If we include the impact of his rescission, he deserves credit for shrinking the welfare state by more than 2.8 percentage points of economic output.

Now it’s time for two caveats.

- Reagan and Congress rescinded budget authority, which is not the same as budget outlays (in simple terms, budget authority puts money in an agency’s checkbook and budget outlays is when the money gets spent). It’s possible, of course, that the authority and outlay effects of the rescissions were not identical.

- I also assumed that all of the rescissions reduced domestic discretionary spending, which seems reasonable given that Reagan promised to boost military spending and shrink the welfare state. But the GAO study (as well as this report from the Congressional Institute) don’t provide that level of detail.

The bottom line is that I am completely confident in the numbers I calculated in 2020 but only reasonably confident in the rescission-adjusted numbers in today’s column.

That being said, these new numbers are closer to the truth and they further demonstrate that Reagan did a remarkable job of restraining the size and growth of the federal government. Another win for Reaganomics.

P.S. Several readers have asked me why I haven’t updated the presidential spending numbers to include the last two years of Trump’s first term and the four years of Biden’s presidency. The answer is that I’m not sure how to measure the impact of the supposed emergency spending during the COVID pandemic. As a general principle, I don’t think presidents should be blamed (or credited) for unexpected one-time events, which is why my 2020 calculations exclude the impact of TARP (along with the Savings & Loan bailout more than 30 years ago). Yet it’s also true that politicians used the pandemic as an excuse to shovel money to various special interests, so I don’t want to give Trump or Biden a free pass for the 2020-2021 spending orgy. Given these difficulties, I don’t think there’s a fair way of handling the issue. But I have no hesitation in stating that both of them were fiscally irresponsible.

P.P.S. I also have never bothered to rank Gerald Ford because of his short time in the White House.

P.P.P.S. You have to go back to Harding and Coolidge to find presidents who were analogous to Reagan.

P.P.P.P.S. For those interested in international comparisons, there are examples of governments that have done a reasonably good job of spending restraint, at least for certain periods of time. Sweden and Taiwan also are good case studies. But nothing compares to Javier Milei’s first year in office.