I’m speaking today in Uruguay and, since this is my first visit, I want to take this opportunity to analyze that country’s economic policy.

The good news is that the current president, Luis Lacalle Pou, has been more fiscally responsible than his predecessors.

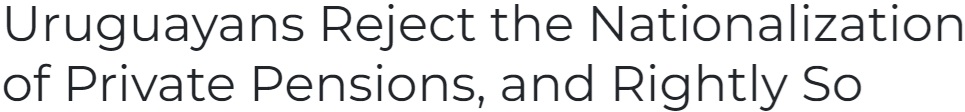

Here’s a chart looking at average annual changes in the burden of government spending, based on the IMF’ database. As you can see, the current president is hardly a Milei-style budget cutter, but at least he’s not as profligate as politicians from the Broad Front.

The president’s most important reform almost certainly has been to the government-run portion of Uruguay’s pension system.

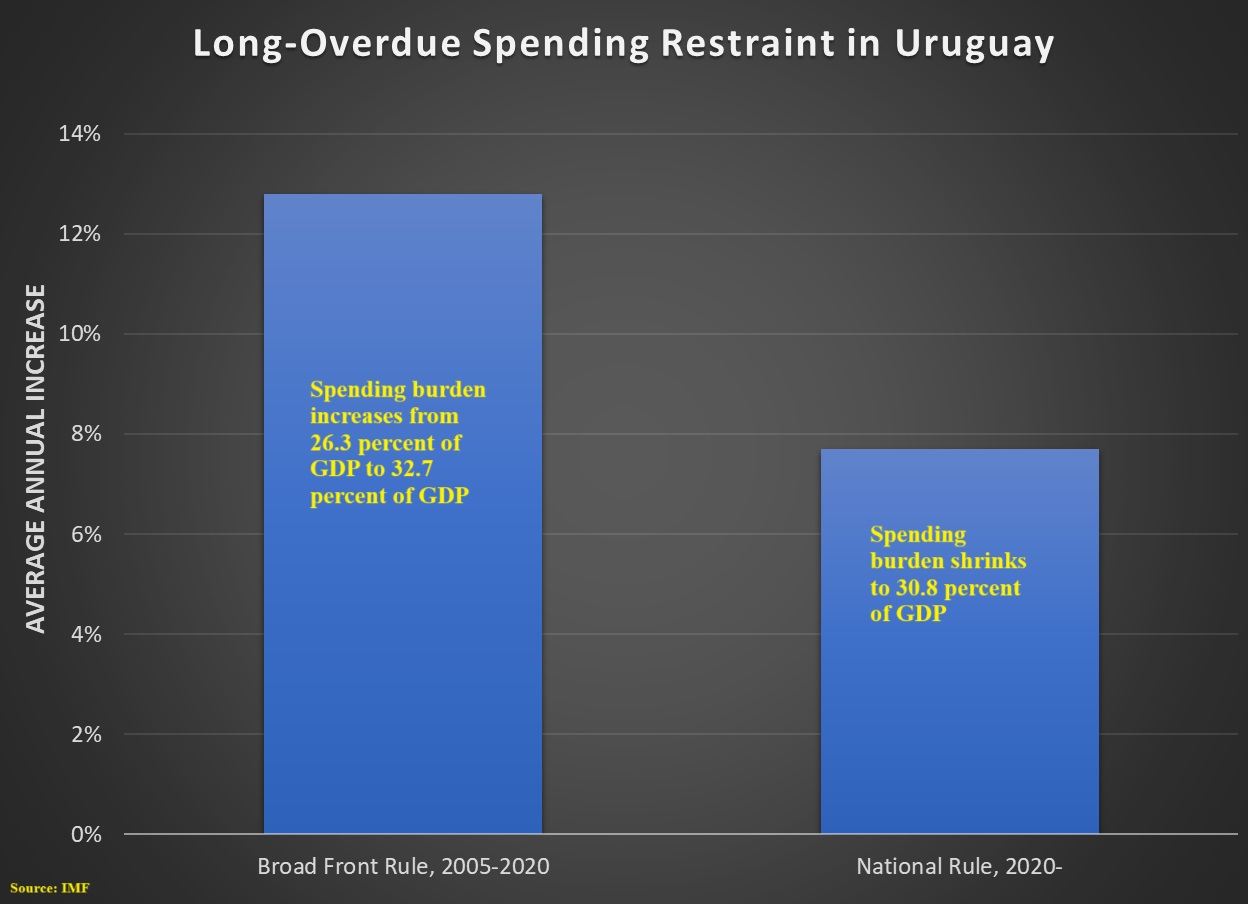

The retirement age has been increased. Combined with other changes, this will yield significant savings for taxpayers.

Here’s an estimate of long-run savings according to a recent analysis.

This is very impressive, especially considering that the United States just had an election with two politicians who ducked the issue.

Interestingly, Uruguay voters seem to have sensible views on pensions. The left put a referendum on the ballot that would have lowered the retirement age back to 60 and also nationalized the nation’s private retirement accounts.

As explained by Marcos Falcone in a column for the Foundation for Economic Education, voters overwhelming rejected this statist initiative.

A few weeks ago, …Uruguayans…went to the polls to decide on a proposition that raised some eyebrows both at home and abroad: the nationalization of private social security, along with the lowering of the retirement age from 65 to 60 and the establishment of a minimum pension equivalent to the national minimum salary. …39 percent of Uruguayans…voted in its favor… After all, the nationalization of social security implied the end of private pension schemes, with the effective confiscation of hundreds of thousands of private savings accounts to follow, capital flight, and significantly lower levels of investment. Up to USD 1.5 billion in additional spending was also estimated, in a country of just over 3 million. …Fortunately, Uruguayans ultimately understood the dangers of ending private pension schemes in favor of a state-run social security monopoly, and perhaps also the deep injustice that lies behind such a measure.

Now that I’ve shared some good news about Uruguay, let’s shift to bad news.

First and foremost, Uruguay is not a rich country.

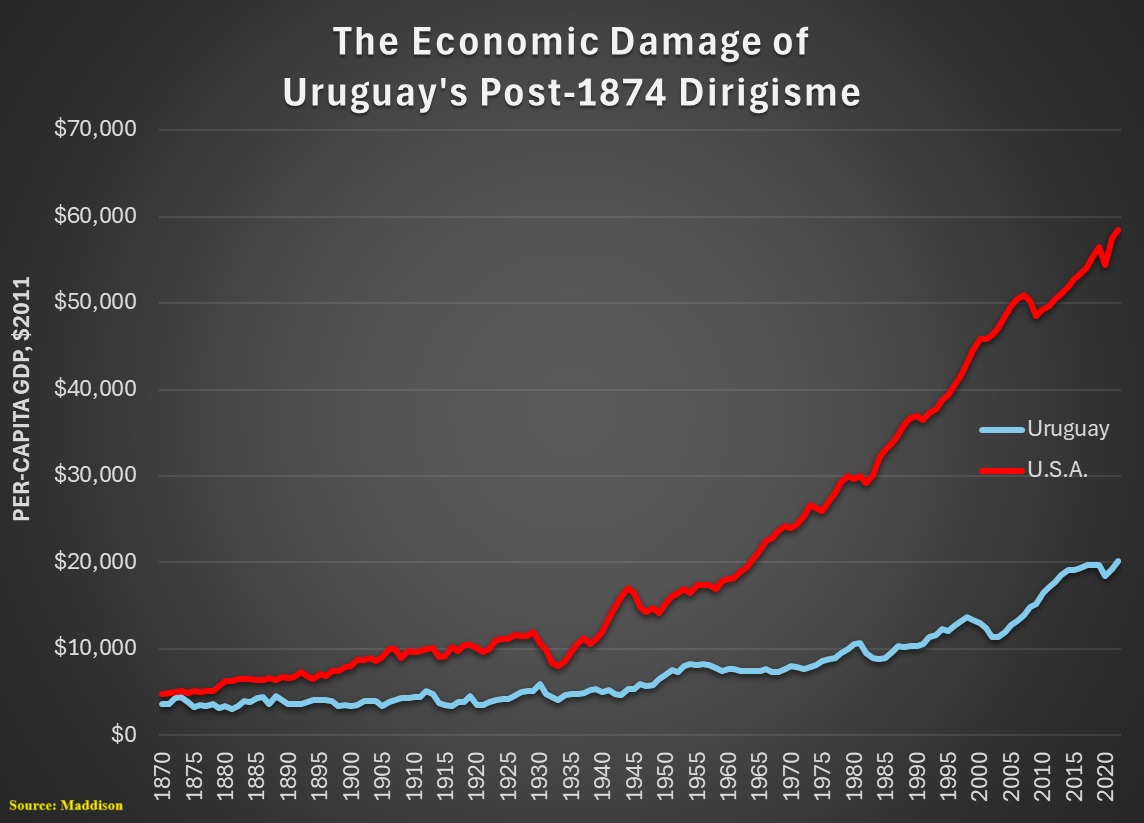

But if you go back about 150 years, it was almost equal to the United States. Unfortunately, this was when Uruguay began to shift away from markets.

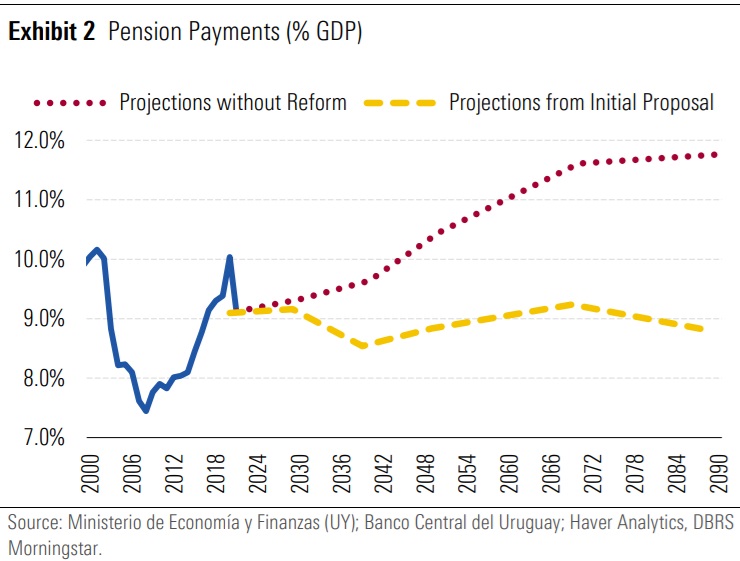

At the conference where I’m speaking, one of the Uruguayans shared a slide showing the economic history of his country divided into three periods. The country had classical liberalism for its first several decades, followed by about 100 years of bad policy, and then some modest improvements over the past 50 years.

As you might expect, the 100 years of bad policy had a negative effect.

The Maddison data shows that Uruguay was almost as rich as the United States back in the early 1870s.

But it then began to fall far behind America during its “dirigista” period (indeed, it could be a member of the anti-convergence club).

For all intents and purposes Uruguay made the same mistake as Argentina, but it went in the wrong direction starting in the 1870s instead of waiting until after World War II (which is when Argentina began to rapidly degenerate).

But I’ll now shift back to some good news. Economic policy moved in the wrong direction in Uruguay, but not nearly as far or as fast as it did in Argentina. So while any nation would benefit from a Milei-style libertarian leader, Uruguay can get away with a more modest pace of reform.

But I have no idea whether that will happen.

P.S. For readers who care about non-economic issues, Uruguay ranks high for personal freedom and has a reasonably laissez-faire attitude about issues such as guns and marijuana.

———

Image credit: Elias Rovielo | CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.