The newest edition of Economic Freedom of the World has been released by the Fraser Institute and I will continue my tradition (2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, etc) of sharing the big-picture highlights.

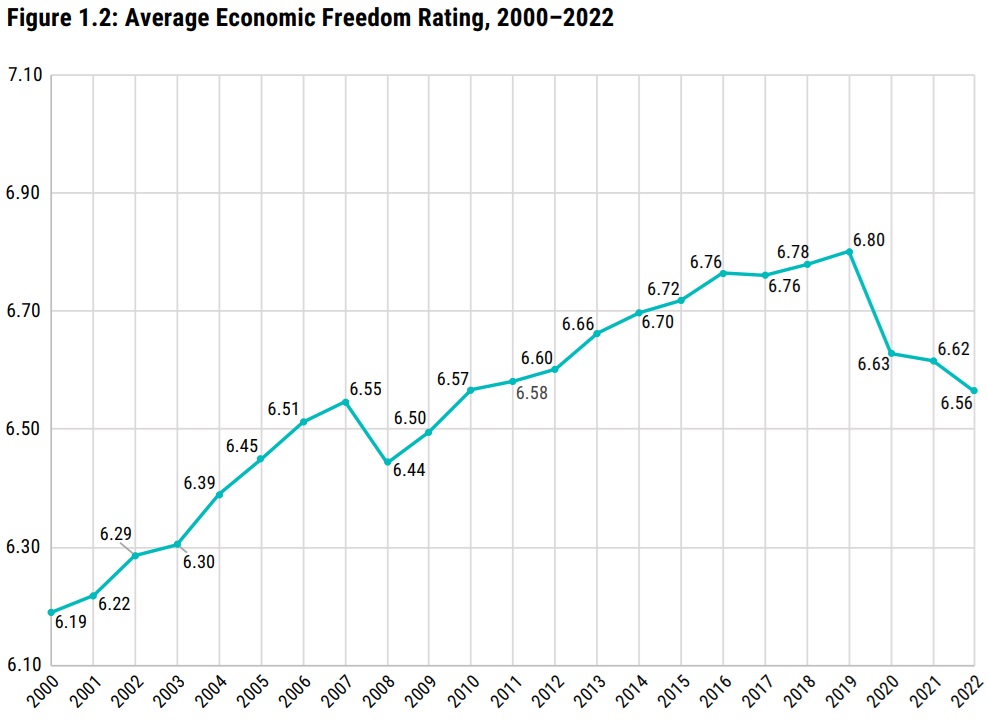

I normally start by applauding the jurisdictions with the highest scores, but today’s column will start with some bad news for the global economy. As shown by Figure 1.2, there’s been a significant drop in average economic liberty over the past three years.

This is a depressing reversal of what had been a very positive trend this century.

What’s particularly disappointing is that rise in the global average had been driven by pro-growth reforms in the developing world (scores have dropped this century for the United States and European Union). Now it seems policy is getting worse in all regions.

Now that we’ve shared that bad news, let’s look at the (relative) good news.

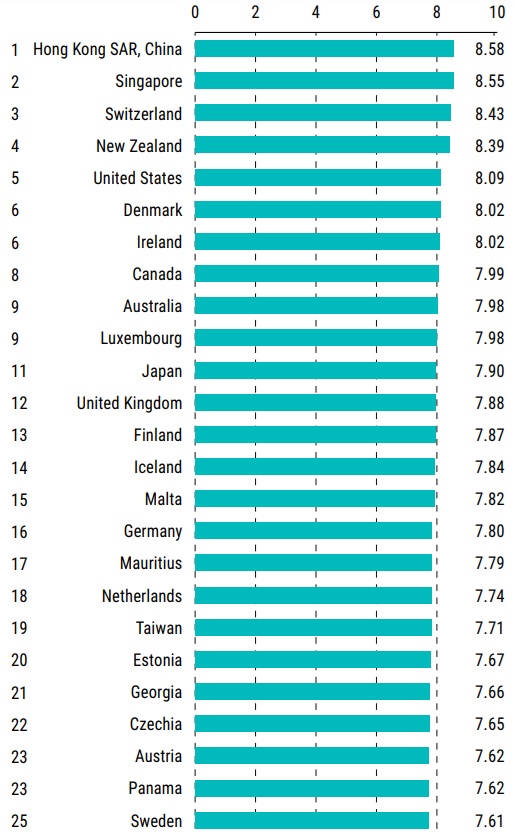

Here are the world’s 25-freest jurisdictions. Interestingly, Hong Kong is still at the top even though the report warns that “Hong Kong’s rating continues to fall precipitously from 9.05 in 2018 to 8.58 in 2022.”

Kudos to Singapore, Switzerland, New Zealand, and the United States for being in the top 5 (though the U.S. score has fallen significantly since 2000 – from 8.83 to 8.09).

Before sharing other visuals, here are a few excerpts that explain the methodology in the report.

The EFW index is designed to measure the degree to which the institutions and policies of countries permit people to make their own economic choices. To achieve a high EFW rating, a country’s government must do some things, but refrain from others. Governments protect economic freedom when their laws safeguard voluntary exchange and defend individuals and their property from aggressors who might use fraud or force. To this end, the legal system is a particularly important guarantor of economic freedom. In more economically free places, legal institutions protect the person and property of all individuals from the aggressive acts of others and enforce contracts in an even-handed manner. These governments also permit people to access sound money and do not expropriate property through unexpected inflation or deflation. In economically free places, governments refrain from actions like high taxation, barriers to trade, and excessive regulations that restrict personal choice, interfere with voluntary exchange, and limit entry into markets. The EFW index might be thought of as an effort to identify how closely the institutions and policies of a country correspond with the classical liberal ideal of a limited government, where the government protects people and property rights from aggressors but otherwise allows them to make their own economic choices.

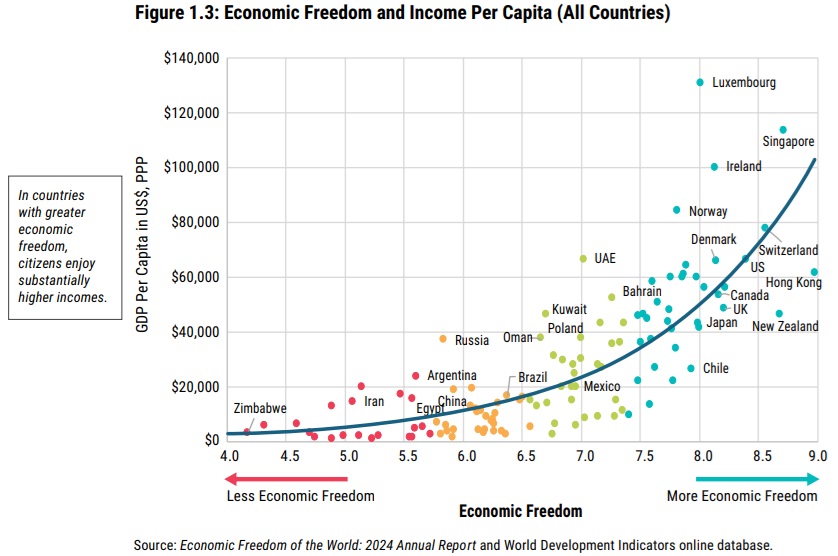

And good things happen when people “make their own economic choices.”

Here’s a chart showing the very clear relationship between economic freedom and national prosperity.

Gee, it’s almost as if there’s a recipe that nations can follow if the goal is more prosperity.

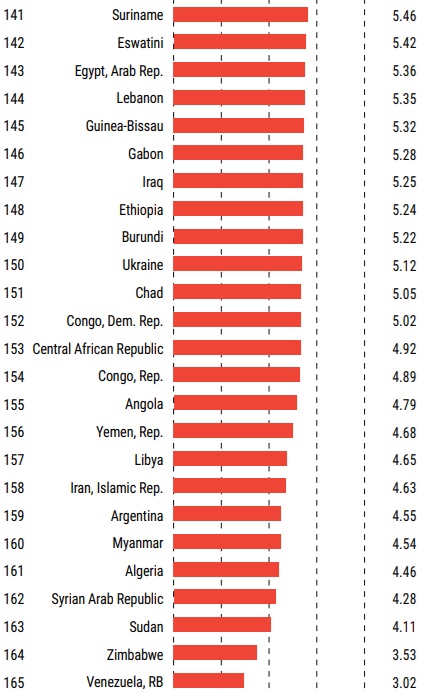

Let’s now close with bad news. Unsurprisingly, the world’s lowest-ranked nation is Venezuela (though Cuba and North Korea would probably be even lower if there was enough reliable data to include them in the report).

P.S. Argentina is still one of the world’s worst nations for economic policy because EFW measures policy as of the end of 2022. Yes, that nation now arguably has the world’s best leader, but he didn’t take office until the end of 2023 and his positive reforms (see here, here, and here) have been implemented this year. So we’ll have to wait two years to see (what I predict will be) a big improvement.