Responding to Hurricane Harvey last year, I shared three very good videos explaining why laws against “price gouging” are misguided.

Simply stated, politicians can’t wave a legislative wand and change underlying conditions of supply and demand.

Laws that artificially dictate the price of something almost surely will have adverse consequences (just as artificially setting the price of labor causes some joblessness and artificially controlling price of health insurance can cause a death spiral).

Needless to say, this is not a welcome observation in some quarters.

John Stossel addresses price gouging in a new Townhall column. He starts by describing the political response.

Officials in states hit by Hurricane Florence are on the lookout for “price gouging.” People who engage in

“excessive pricing” face up to 30 days jail time, said North Carolina’s attorney general. South Carolina passed a “Price Gouging During Emergency” law that imposes a $1,000 fine per violation. …These are “bad people,” said Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi angrily during a previous storm.

He then explains some basic economics.

Pursuing profit is simply the best mechanism for bringing people supplies we need. Without rising prices indicating which materials are most sought-after, suppliers don’t know whether to rush in food, or bandages, or chainsaws. …Who will bring supplies to a disaster area if it’s illegal to make extra profit? It’s risky to invest in 19 generators, leave home, rent a U-Haul and drive 600 miles. …If prices don’t shoot up during disasters, consumers hoard. We rush to gas stations to top off our tanks. Stores run out of batteries because early customers stock up. Late arrivals may get nothing. … America should have learned that when Richard Nixon imposed price controls on gasoline. That gave us gasoline shortages and long gas lines. …allowing prices to rise, even sharply, is the best way to help desperate people get supplies they need. As supplies rush in, prices quickly return to normal. We shouldn’t call it gouging. It’s just supply and demand.

He concludes with some advice that politicians almost certainly will ignore.

The best thing “price police” can do in a disaster is stay out of the way.

Price police? I wonder if they get the same training as the milk police and bagpipe police?

But I’m digressing.

I’m going to augment Stossel’s analysis with some simple supply-and-demand curves. We’ll start with a look at a normal, competitive market. The supply curve shows producers are willing to provide ever-larger amounts of a product at higher and higher prices.

Conversely, the demand curve shows that consumers are willing to buy a lot of a product when prices are low, but the quantity they want declines as prices increase.

The “equilibrium price” is where the two curves intersect.

Now imagine you live in North Carolina and the hurricane is wreaking havoc. Two things are likely to happen. First, some sellers will be knocked out of the market. Maybe they lost power, got flooded, or went someplace safe for the duration of the storm.

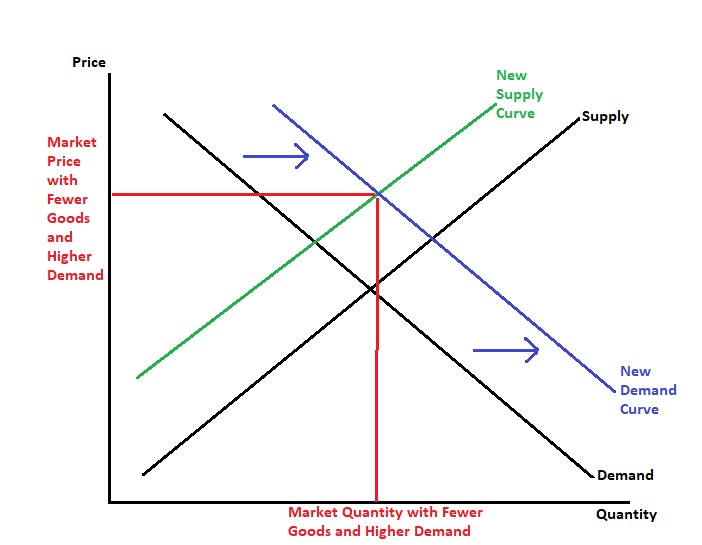

The real-world impact is shown by this next graph. The supply curve has shifted to the left, meaning that there is less product available at any given prices. The net result is that the market price will go up.

The second effect is that there presumably will be more demand. Consumers will suddenly decide that certain goods (milk, bread, candles, batteries, generators, plywood, etc) are more valuable than they were last month.

This chart shows the effect of increased demand.

By the way, the way I randomly created the charts shows the quantity staying roughly the same, but that all depends on market conditions. Prices can rise a lot or a little, and quantity demanded can fall a lot or rise a lot.

Here’s all you really need to understand. If the government has anti-gouging laws that prevent prices from adjusting to market conditions, the result will be a shortage.

Which is what’s depicted in this chart. Consumers will want a lot of the product, but they won’t be able to find enough willing sellers.

That might seem like a good outcome if you were one of the lucky people who was willing to wait in line or otherwise got lucky (the “seen”). But it means a lot of consumers get left out (as Bastiat points out, those are the “unseen”).

For instance, look at what happened after Hurricane Sandy, for instance.

Perhaps most important, it means that there’s very little incentive for entrepreneurs to incur a lot of expense and effort to get much-needed supplies to a disaster area.

So people would be left waiting for the government, which means a sluggish reaction and often the wrong kind of help.

None of this suggests that “price gougers” are heroes. Yes, some of them take a risk with time and money (and maybe even personal safety) by rushing to a disaster zone. But others simply want to take advantage of an opportunity to jack up prices and get a windfall.

My point is simply that laws against gouging are bad since many consumers will be denied the opportunity to get desperately needed goods and services.

P.S. If you want more evidence of the folly of price controls, see how they backfired in Puerto Rico and Venezuela.

P.P.S. The post-war German economic miracle was triggered by the removal of price controls.