My opinion on taxing corporate income varies with my mood.

When I’m in a fiery-libertarian phase, I want to abolish taxes on corporate income for the simple reason that all income taxes should be eliminated. Heck, I would also eliminate October 3 from the calendar because that’s the awful day in 1913 that the income tax was signed into low.

But when I’m going through a pragmatic-libertarian phase, I grudgingly accept that my fantasies won’t be realized and focus on incremental reform. And that means I want a simple and fair system like the flat tax, which is based on the principle that all income should be taxed, but only one time and at one low rate.

But when I’m going through a pragmatic-libertarian phase, I grudgingly accept that my fantasies won’t be realized and focus on incremental reform. And that means I want a simple and fair system like the flat tax, which is based on the principle that all income should be taxed, but only one time and at one low rate.

And that means corporate income should be taxed.

That being said, while it may be appropriate to tax corporate income, that does not mean the U.S. corporate income tax is ideal.

- The rate is too high, making America less competitive.

- Because of the corporate income tax and the personal tax on dividends,corporate income is double taxed.

- Rules on “depreciation” force companies to overstate their income.

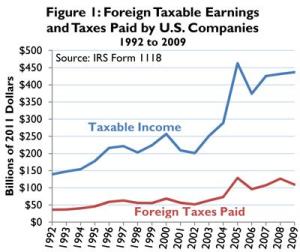

- The system of “worldwide taxation” requires American-domiciled firms to pay tax on income that was earned – and already subject to tax – in other jurisdictions.

- There are unjustified and distortionary loopholes that result in zero tax on some types of income/activities.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that all of these problems can be solved with a flat tax, which would rip of the current corporate income tax and replace it with a very simple, low-rate system that properly measures income (i.e., expensing and territorial taxation) and taxes it only one time (i.e., no double taxation).

By the way, corporate income can be taxed without a corporate income tax. Simply tax the income when it is distributed to shareholders (the people who own the company) instead of taxing it at the business level. The goal, of course, is to make sure it no longer gets taxed twice.

By the way, corporate income can be taxed without a corporate income tax. Simply tax the income when it is distributed to shareholders (the people who own the company) instead of taxing it at the business level. The goal, of course, is to make sure it no longer gets taxed twice.

A good business tax system isn’t a fantasy. Jurisdictions such asEstonia and Hong Kong have business tax systems that are very close to the aforementioned ideal. And it goes without saying that jurisdictions such asBermuda, Monaco, and the Cayman Islands. are even better since they fulfill my dream of no income tax whatsoever.

With this background on good business tax policy, let’s now look at some contentious issues and see how they should be addressed.

We’ll start with the kerfuffle over companies that don’t pay tax, a controversy that was triggered by a somewhat disingenuous report from the Government Accountability Office.

One of the takeaway headlines from the GAO report is the supposedly startling revelation that 70 percent of corporations paid no tax.

But Aparna Mathur of the American Enterprise Institute explained the real story, which is that they didn’t pay tax because they didn’t have profits.

In 2012, out of 1.6 million corporate tax returns, only 51% were returns that had positive “net incomes,” and only 32% were returns that had positive “incomes subject to tax.” …“income subject to tax” allows companies with positive “net incomes” to claim an additional deduction as a result of prior-year operating losses. These losses can be carried forward to offset taxable incomes in years when firms are making a profit or have positive net incomes; this is known as a net operating loss deduction (NOLD). For 2012, the data show that approximately 20% of companies with positive “net incomes” (or profits) claimed a net operating loss deduction resulting in a zero tax liability.

There’s a bit of jargon in that passage, but the main thing to understand is that companies get to use losses from one year to offset profits from another year, which means – for all intents and purposes – that the government’s definition of taxable income does a better job of measuring profits over a longer period of time.

Here are some more details.

…the data shows two things: first, the GAO claim that 70% of companies paid no income tax is largely because more than 50% of these companies had zero profits or net incomes, and therefore they had zero tax liability. Secondly, some of these currently “profitable” (positive net income) companies have experienced large losses in prior years. For these companies, the NOL deduction allowed them to reduce their tax liability to zero. …The intent of this provision is, for example, to avoid a company with 5 years of consecutive operating losses of $20 million each having to pay income tax in year 6 simply because it realizes income of $20 million in that year. The principle underlying NOLD is intended to allow companies to get out of the hole of accumulated losses before the government can start claiming…the company’s income.

Her conclusion is completely sensible and appropriate.

…the GAO clearly acknowledges that the reason 70% of companies are paying no taxes is because they are either not currently profitable or they are able to offset taxes because of prior-year losses.

The Tax Foundation also has weighed in on this issue.

…the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report on corporate income taxes, which found that 19.5 percent of “profitable large corporations” paid zero corporate income taxes in 2012. …Should you be…outraged…about the number of U.S. corporations that pay no corporate income tax? In fact, there is good reason to think that many of the corporations that the GAO identifies as “profitable” did not actually earn a profit. In such cases, it would have been a mistake to collect corporate income taxes from these companies.

Echoing the explanation from Ms. Mathur, the Tax Foundations makes the same point about current year profits being offset by prior years’ losses, but also add a few additional reasons why “profitable” companies aren’t paying tax.

…some of the corporations that were categorized as “profitable” by the GAO in 2012 did not actually earn positive profits in the United States. …To the extent that some of the “profitable” corporations in the GAO report earned only foreign profits, rather than domestic profits, it is entirely reasonable that these corporations should not be subject to any U.S. corporate tax burden.

Particularly since they already are paying lots of tax on their foreign-source income to foreign governments.

There’s also the issue of depreciation, which journalists always have a hard time understanding.

…when calculating a corporation’s economic profit, it is appropriate to treat the entire cost of an investment as a current year expense. …imagine a corporation with $1 million in operating profits and $2 million in investment costs. Depending on how much of the investment the corporation treats as a current-year expense, the corporation could be making a large profit, no profit, or negative profit.

The bottom line is that you have look closely at how government defines “profit” to correctly ascertain whether companies are somehow avoiding taxation.

And in most cases, you’ll discover that the firms that don’t pay tax are the ones that don’t actually have income, properly defined.

…some U.S. corporations with positive book income might have negative taxable income: not because of any tricks or loopholes, but simply because the tax code operates under different accounting rules. …there are real, legitimate reasons why a “profitable” corporation would not and should not be required to pay corporate income taxes in a given year.

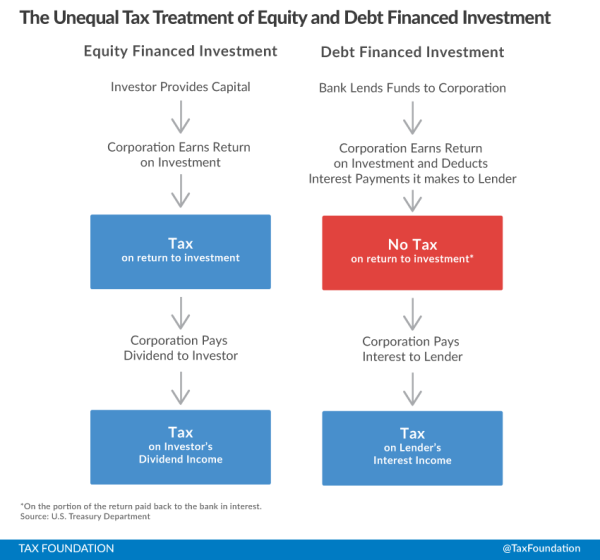

Now let’s return to the issue of double taxation, which occurs when income is taxed at the business level and then a second time when distributed as dividends to shareholders.

The Tax Foundation nicely summarize the issues in a new study, including some much-deserved focus on how this creates a bias for debt.

…income that is earned by corporations and funded by equity (stocks) is subject to a double tax: once on the corporate level, when it is earned, and once on the shareholder level, when it is distributed as dividends. The double taxation of equity-financed corporate income leads to several major economic distortions. It encourages investors to shift their investments from corporate to non-corporate businesses, leading to a less efficient allocation of capital. Furthermore, it incentivizes corporations to fund their operations with debt, rather than equity, leading to excessive leverage.

The solution, needless to say, is something called “corporate integration,” which is simply a wonky way of saying that income should be taxed only one time.

Corporate integration refers to a set of proposals to standardize the taxation of business income across legal forms and methods of financing. The chief advantage of corporate integration is that it would end the double taxation of equity-financed corporate income… The principle of tax neutrality – that a tax system should neither encourage nor discourage specific economic decisions – is embraced by public policy scholars throughout the political spectrum. Corporate integration – taxing all business income at the same top rate, regardless of the legal form of the business or how the income was financed – would minimize the economic distortions created by the U.S. tax code and conform to the principle of neutrality.

Here’s a chart showing how neutrality is violated by double taxing income that is generated by equity. Once again, there’s a bit of jargon, but the main thing to understand is that companies deduct interest payments they make to bondholders, so there’s a tax at the household level but no tax at the business level. But they can’t deduct dividend payments, which effectively means the company is taxed on that money in addition to the household paying tax as well.

The Tax Foundation helpfully suggests how this inequity could be resolved. Allow companies to deduct dividend payments, just as they now deduct interest payments.

Perhaps the simplest way to integrate the corporate and individual tax codes would be to tax dividends received by individuals at ordinary income rates and allow corporations to deduct all of their dividends paid.

Incidentally, this would basically mean that there’s no longer a corporate income tax, though (as discussed above) all corporate income would still be taxed (at the household level).

Let’s close by looking at two pieces of legislation and applying the lessons we’ve learned.

Congressman Devin Nunes (R-CA) has legislation that would address many of the problems outlined above. Here’s how the Tax Foundation describes his plan.

Major elements of his plan are: Cutting the corporate income tax to 25 percent; Limiting the top tax rate on non-corporate business income to 25 percent; Allowing businesses to deduct investment costs when they occur (full expensing); Eliminating most business tax credits and many deductions; Moving to a territorial tax system like most developed nations; …Applying the same tax-rate limitation to individuals’ interest income as now applies to their capital gains and dividend income; and Eliminating the individual and corporate alternative minimum taxes (AMTs).

Wow, that’s fixing many of the problems outlined above.

But here’s the catch. To make the numbers add up, he gets rid of the bias for debt. But he does it by adding a second layer of taxation to interest income rather than abolishing the second layer of tax on dividend income.

The Nunes plan would not let nonfinancial businesses deduct interest payments, but would not tax them on interest receipts. It would generally not allow individuals to deduct interest payments, except that home mortgage interest would remain deductible, and it would apply the same tax-rate limitation to individuals’ interest income as to dividends (top rate of 20 percent). These changes would have a mixed effect on tax biases. On the one hand, they would lessen the tax distortion at the corporate level between debt and equity financing. Because debt is riskier than equity (debt payments are legally required regardless of business cash flow), corporate businesses would be better able to weather economic adversity if the tax system did not push them so strongly toward debt financing. On the other hand, the changes would mean that corporate returns financed through debt would be taxed at both the corporate and individual levels, as is now the case with corporate equity.

For what it’s worth, the Tax Foundation projects that Cong. Nunes’ plan would be very beneficial to growth and job creation, so the benefits of the good reforms are much larger than the harm associated with extending double taxation to interest payments.

That sounds right to me, particularly when you include the fact that companies will make sounder decisions once there’s no longer a bias for debt.

Last but not least, let’s review some recent legislation from Congressman Tom Emmer (R-MN).

Here’s what Americans for Tax Reform wrote about his proposal.

Currently, the U.S. corporate rate is the highest amongst the 34 country Organisation for Economic Development (OECD). At 39 percent, it far exceeds the OECD average rate of 25 percent, and is even further behind developed countries like Ireland, Canada, and the U.K. which have rates of 20 percent or less. The CREATE Jobs act would fix this by reducing the U.S. corporate rate to five points below the OECD average and creating a process by which the U.S. rate is regularly reviewed to ensure economic competitiveness. …bringing the rate below the OECD average would have strong and immediate effects. A 20 percent U.S. corporate rate could create more than 600,000 jobs, increase GDP by 3.3 percent, and increase wages by 2.8 percent over the long-term, according to the Tax Foundation.

P.S. Here’s a CF&P video that describes some of the warts associated with the corporate income tax.

———

Image credit: geralt | Pixabay License.