The Economic Benefits of Peace in Ukraine

By Daniel J. Mitchell and Robert O’Quinn

Executive Summary

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has led to reduced international trade and investment. In large part because of economic sanctions, American exports to Russia have declined, as have American imports from Russia. The same is true for Ukraine, but to a lesser extent and only because of regional conflict rather than restrictions by the U.S. government.

Even more important, at least from an economic perspective, is that the ongoing conflict is creating significant risks for the U.S. economy—everything from putting at risk the role of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency to significant potential losses for critical industries such as energy and aviation.

Ongoing efforts by the Trump Administration and others to end the war without rewarding Russian aggression are very desirable, most notably because it would put a stop to the death and destruction. But an end to hostilities would be economically beneficial as well. Russia and Ukraine could begin to rebuild and grow as more resources get left in the productive sector of the economy instead of being diverted for military use.

The United States also could benefit from peace between Russia and Ukraine. Some of the most notable effects include:

- Once hostilities end, Ukraine doubtlessly will be given hundreds of billions of dollars of aid. American companies will have a massive opportunity to win a major share of rebuilding contracts.

- The United States enormously benefits from the dollar being the world’s reserve currency. Nations such as Russia and China would like to end this “exorbitant privilege”[1] and are using the war, as well as trade tensions, to undermine America’s position. This major macroeconomic risk will be much less likely to materialize if and when the war ends.

- A peace agreement would be specifically important for two systemically important industries, with enormous potential benefits United States.

- Energy – American companies such as ExxonMobil have lost billions of dollars because of the conflict and the resulting sanctions. Ending the war would enable U.S. firms to recoup some of that business, but the real goal is making sure American companies can compete for what could be hundreds of billions of dollars of long-run future business (Arctic exploration, LNG, etc).

- Airlines – A major threat to Boeing is the development of China’s commercial aviation industry. The longer the war lasts and a sanctions regime is in place, the greater the risk that Russia, India, and other countries will decide that it is in their interest to abandon American-manufactured aircraft – thus leading over time to tens of billions of dollars in lost sales.

- Ending the war presumably would lead to a return of normal trade patterns among and between the three nations, with a baseline effect of about $25 billion of additional American exports per year.

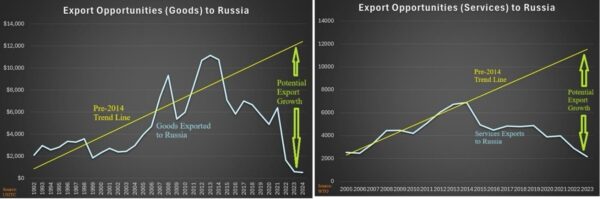

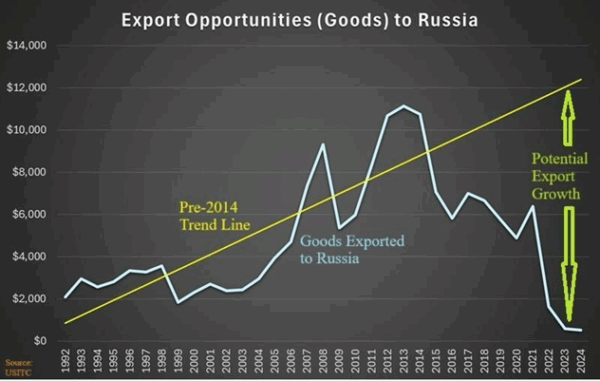

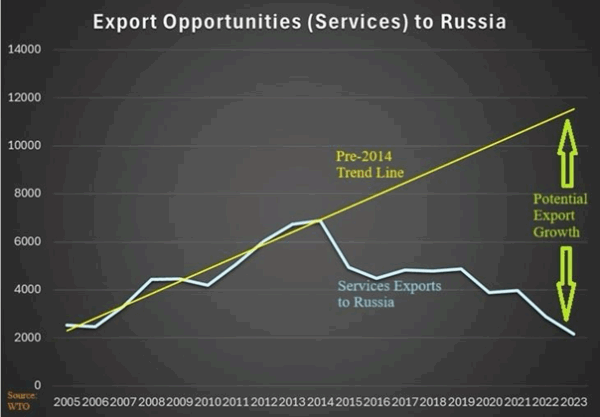

As shown by these two charts and discussed in greater detail in the body of this report, restoration of trade could be very beneficial for American exporters. Based on trend analysis of pre-2014 trade flows, American companies would be able to increase sales by more than $20 billion.

Trade normalization also would allow American companies and households to benefit from increased imports from Russia and Ukraine, though the increase presumably would not be as significant since a big share of those nations’ exports (oil and agricultural, respectively) are in areas where the United States is either entirely or largely self-sufficient.

Introduction

Following Russia’s takeover of Crimea in 2014, many nations expressed disapproval by imposing various economic sanctions to limit trade. Further restrictions on trade were imposed after Russia invaded the rest of Ukraine in 2022. These sanctions (outlined in Appendix I) have not dissuaded Russia’s aggression, and President Putin’s government has figured out strategies to evade or adjust to the restrictions. Nevertheless, trade barriers are not good for prosperity. They hurt the nation being sanctioned, while also denying gains from trade for the nations imposing sanctions.

The purpose of this report is to analyze the potential economic benefits to the United States that will accrue once hostilities cease and normal economic relations are reestablished. Part of the methodology is very straightforward, looking at pre-2014 trend lines to estimate potential levels of trade today. As described in Appendix II, the report primarily uses data on trade flows from the World Trade Organization when making calculations, augmented by numbers from International Trade Commission.

This research will show some benefit from expanded trade with Ukraine. Imports from exports have both been hindered by the war. A cessation of hostilities would create opportunities for American importers and exporters.

But bigger gains will accrue because of renewed trade with Russia. Both exports and imports have dramatically decline over the past decade. Restoring normal economic relations would give Americans – particularly manufacturers – greater access to Russian goods, especially raw materials. The biggest effect of normal trade relations, however, would be expanded export opportunities. Based on trend line analysis of both goods and service, exports from the United States to Russia would increase by more than $20 billion annually.

The more challenging part of the report – and the part that has the biggest implications – are the estimates of how continued conflict could damage the American economy and deprive U.S. firms of hundreds of billions of dollars of business over the next few decades.

Economic Risks to the Dollar

One of the most under-appreciated risks of continued conflict is that it gives foreign nations (especially those who are not U.S. allies) an ever-greater incentive to undermine the role of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. The “exorbitant privilege’ is very beneficial for the American economy, including lower interest rates.

According to a 2018 article in the Cayman Financial Review, “empirical studies suggest the privilege is worth about ½ percent of U.S. GDP (or roughly $100 billion) in a normal year.” That number presumably would be significantly higher today.

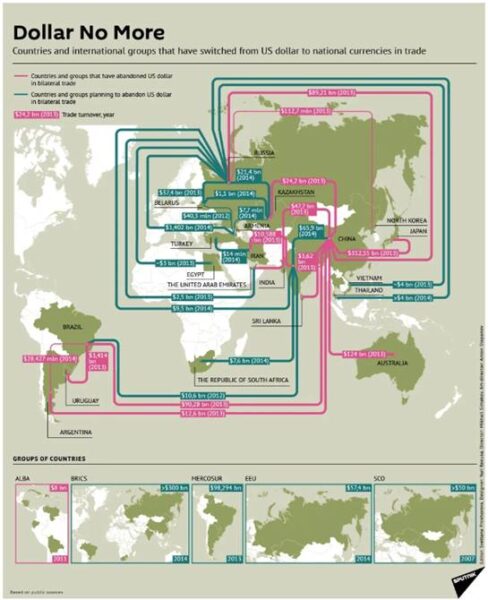

That’s the good news. The bad news if that Russia and China already have been shifting away from using the dollar for international reserves and international transactions. And, as shown in this illustration, this started well before the invasion of Ukraine.

Today, there is even greater incentive for Russia and China to dethrone the dollar. And because of sanctions and secondary sanctions, many other nations are sympathetic to that outcome. It’s almost impossible to overstate the downside risk for America. Many countries hold U.S. Treasury bonds as part of their foreign exchange reserves because the dollar is the dominant reserve currency. If the dollar lost that role, foreign central banks and investors would hold fewer Treasuries.

With less foreign demand, U.S. Treasury prices would fall and interest rates would rise. Higher Treasury yields would cascade throughout the economy, raising:

- Mortgage rates

- Corporate borrowing costs

- Credit card and loan rates

This would make financing more expensive for consumers, businesses, and the government. With about $30 trillion of debt, even a modest 1-percentage point increase in interest rates would dramatically increase America’s fiscal problems.

Lost Business for American companies

There are two major sources of forgone business for U.S. firms. The loss of exports will be addressed in the next section. This section will cite two examples to illustrate how ongoing conflict is leading to missed investment opportunities and threats to a significant sector.

- The missed opportunity is in the energy sector. Russia is very rich in natural resources.[2] Most notably, it reportedly has more than 200 billion barrels of proven oil reserves.[3] Perhaps more importantly, it also has more than 60 trillion cubic feet of natural gas according to other reports.[4] Before annexation of Crimea, ExxonMobil had agreements to play a major role in the exploration, development, and production of some of those resources.[5] Needless to say, that no longer is happening, either for ExxonMobil or other American firms. Since Russian energy reserves exceed $1 trillion, the forgone business from joint ventures could be enormous, potentially above $100 billion.

- One of the spin-off effects of the war in Ukraine is that Russia’s aviation sector is suffering because sanctions are making it difficult to maintain the planes purchased from Boeing. Another spin-off effect of the war is that China is much more closely allied with Russia. The combination of these two factors likely will accelerate the competitive pressure than Boeing is going to face from China’s civil aviation industry. Particularly since other nations, even friendly ones, are unhappy about U.S. extraterritorial sanctions and protectionism. What are the consequences? With annual sales of $50 billion-$100 billion[6] and direct and indirect employment of more than 1,000,000[7], it would be a heavy blow to American competitiveness for Boeing to lose a competitiveness battle with China.

History of US-Russia and US-Ukraine Trade

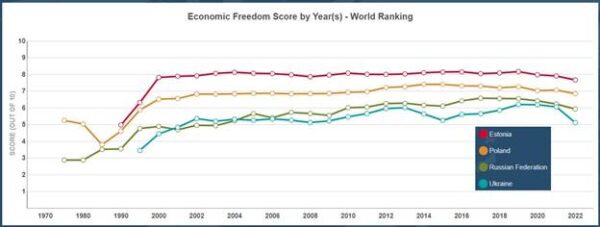

During the Cold War, there was very little trade between the United States and the Soviet Union. After the collapse of communism about 35 years ago, the Soviet Bloc dissolved and the Soviet Union split into 15 independent nations, including Russia and Ukraine. Some of the newly liberated/newly independent nations immediately shifted to pro-western, market-oriented nations, including most of Eastern Europe and the Baltic nations. Russia and Ukraine, however, only partially liberalized, as shown by this data from Canada’s Fraser Institute.[8]

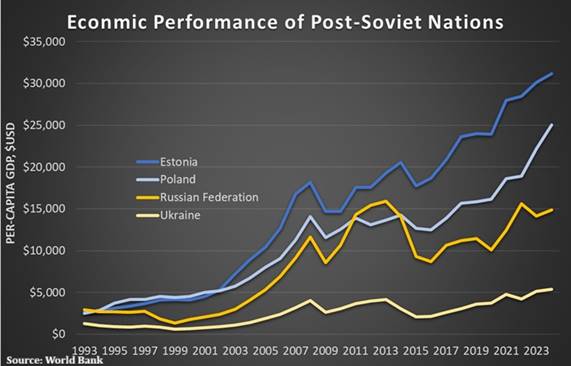

Unsurprisingly, less economic liberalization has meant less economic growth. According to World Bank data, Russia and Ukraine are economic laggards compared to Estonia and Poland.[9] Estonia is twice as rich, per capita, as Russia. Based on current trends, Poland will also be twice as rich within a few years. Meanwhile, Ukraine lags far behind, though perhaps in part because of geopolitical instability.

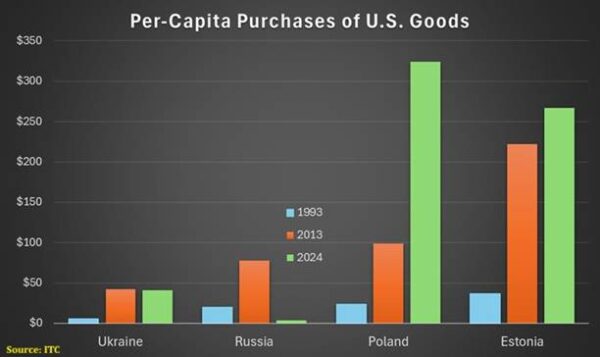

Given the lagging levels of prosperity in Russia and Ukraine, consumers and businesses in those nations are unable to afford as many imports as their counterparts elsewhere. For instance, data from the International Trade Commission in Washington shows that per-capita purchases of American goods in Poland and Estonia this century have been at least three times greater than per-capita purchases from Ukraine and Russia.[10]

Since the United States is far richer than nations from Eastern Europe, particularly Ukraine and Russia, it is unsurprising that American businesses and consumers can afford to buy more from them than they buy from the U.S. This is reflected in data from the WTO on trade flows between the U.S. and Russia, depicted in the following chart. One caveat is that data on services trade is only available for certain years.

Something else to understand is that total trade between Russia and the U.S., as well as trade between Ukraine and the U.S., is a comparatively small share of total cross-border trade for all three nations. For the United States, exports to Russia and imports from Russia are only about one percent of global totals. And the numbers for Ukraine are even smaller.

From the perspective of Russia and Ukraine, trade with the United States is more important. That is unsurprising since the U.S. economy is such a large share of global output. Even so, trade with the United States accounts for no more than five percent of total trade for those two nations.

To summarize, the limited level of cross-border trade is driven by sanctions, regional conflict, and relative poverty.

Benefits of Trade Normalization

While the war in Ukraine currently appears to have no end in sight, hostilities will cease at some point. When that occurs, there will be a significant opportunity for American companies to benefit from renewed trade relations.

The best-case scenario is that there is a peace agreement that enables the end of any meaningful economic sanctions. If that happens, the likely impact on trade flows will be a speculative exercise. That being said, a safe baseline assumption is that trade flows will return to the trend lines that existed before Russia’s invasion in 2022 and before Russia’s takeover of Crimea in 2014.

In the case of Russia, there will be substantial gains for American exporters. This chart takes the 1992-2013 trade trend line for U.S. exports of goods and extends it through 2024. To estimate what this might mean, the chart shows that American companies would have about $12 billion of additional exports compared to the massive drop-off that actually occurred. Given the slope of the line, the level of potential exports in future years would be much greater.

Exports of services from U.S. companies to Russia also would increase significantly if trade is normalized. The next chart repeats the same exercise, calculating the 1992-2013 trend line for services exports and then extending the line to develop an estimate of services exports in a normal trade environment.

For 2024, this would mean an estimated $10 billion of additional services exports for American companies. Once again, the slope of the line indicates that the increase would be significantly larger in future years.

An end to hostilities also would enable American consumers and businesses to buy more Russian-produced goods and service. But the increase in imports presumably would not be as dramatic as the increase in exports for the simple reason that the United States now produces a lot more energy. And since oil and energy-related goods accounted for the lion’s share of imports from Russia before the takeover of Crimea and the invasion of the rest of Ukraine (see chart), a return to normal trade relations presumably won’t lead to a big increase in the purchase of such products.

Regarding trade with Ukraine, American companies don’t face the problem of sanctions. However, the war has caused a drop in exports of both goods and services. When hostilities end, there is every reason to expect those exports also will return to pre-war trendlines. This could mean several billion dollars of annual exports for American firms. There might not be a big increase in imports, however, since a Ukraine historically has exported products – such as wheat and corn – that the United States also exports.

But the more intriguing possibility when considering U.S.-Ukrainian trade is that the war may ultimately lead Ukraine to engage in the type of economic reform that is needed to turn that nation from an economic laggard to a richer nation that can afford to buy a much larger amount of goods and services from the rest of the world.

This is one of the major insights of the late Mancur Olson, a development economist who wrote that very unfortunate events (invasions, occupations, etc) can serve as a trigger for long-overdue economic reforms. Here is some of what he wrote in his most famous book, The Rise and Decline of Nations.[11] First about the impact of World War II.

…countries whose distributional coalitions have been emasculated or abolished by…foreign occupation should grow relatively quickly after a free and stable legal order is established. This can explain the postwar “economic miracles” in the nations that were defeated in World War II, particularly those in Japan and West Germany. The everyday use of the word miracle to describe the rapid economic growth in these countries testifies that this growth was not only unexpected, but also outside the range of known laws and experience. …instability, and war reduced special-interest organizations in Germany, Japan…

Olson made the same observation about the impact of Napolean’s march through Europe in the early 1800s, noting that “Napoleonism…utterly demolished most feudal structures on the Continent and many of the cultural attitudes they sustained.” This enabled the spread of markets and enabled other nations to reap the benefits of industrialization.

Is it possible that economic liberalization could be the silver lining to the dark cloud of war for Ukraine? That is impossible to answer, though it is worth noting that the United States and other nations that have helped Ukraine would be in a very strong position to insist on dramatic reforms to replace statist policies that have caused Ukraine to be one of the poorest nations to emerge from the collapse of the Soviet Empire.

The Cost of Continued Sanctions

The previous section discussed potential benefits of renewed trade following an end to hostilities between Russia and Ukraine. This section will review the consequences if the war does not end and/or sanctions are maintained.

But instead of focusing on aggregate numbers, such as the $20 billion of potential sales discussed above, it may be more instructive to explain how current trade restrictions have harmed specific American companies. In other words, look at the micro impact on firms rather that the macro impact of aggregate trade flows.

Foreign companies — including many based in the U.S. — suffered losses through several distinct channels, mostly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and subsequent countermeasures:

- Non-cash impairments / write-downs. When legal or market developments reduce the recoverable value of an asset below its book value, firms record impairments on their balance sheets. Large asset owners and managers (for example, asset managers or energy partners) marked down their Russian holdings to near zero. BlackRock’s funds, for instance, showed very large reductions in Russia exposure.

- Forced sales / nationalization / seizures. Russian laws and court orders (including so-called “temporary management” and nationalization decrees) enabled transfers of foreign-owned assets at deep discounts to the Russian government or firms without fair market value compensation. KSE documents dozens of such seizures, including some that affected U.S. firms.

- Exit taxes and repatriation restrictions. Russia required companies leaving to pay “exit taxes” and placed practical or legal barriers on repatriating cash held locally. KSE estimates roughly RUB 250 billion (~$2.7bn) collected as exit taxes 2023–mid-2024 and ~ $3bn total in exit-tax burdens. These taxes increase the cash cost of leaving beyond any accounting write-offs.

- Lost revenues and ongoing operating costs before exiting. Some companies such as McDonald’s temporarily ceased operations while paying local staff and bearing fixed costs before exiting Russia.

- Reputational and compliance costs. Firms remaining in Russia, or operating in ways that could contravene the economic sanctions of the United States or other countries in which such firms operate, faced reputational risk or compliance scrutiny — a factor that pushed many firms to curtail activity in Russia.

Some researchers have compiled databases of company-specific losses. The Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) published a report earlier this year estimates that direct losses for foreign companies leaving Russia total $167 billion, of which U.S.-headquartered firms account for roughly $46.0 billion.[12] U.S. losses are concentrated in a small number of very large write-downs (asset impairments or seized assets) and a larger set of smaller charges tied to exits, forced sales and trapped cash.

One year earlier, in March of 2024, journalists at Reuters put together estimates showing losses of $107 billion, though there was not a separate estimate for losses by American-domiciled companies.[13] It is worth noting, however, that the losses have increased by one-third compared to a Reuters analysis released in August of 2023.

KSE’s country breakdown places the U.S. first among countries by aggregate direct losses at about $46.0 billion (KSE examined company filings, Leave-Russia.org, and media accounts to calculate this figure). That $46bn figure reflects impairments, seized-asset valuations and documented forced sale losses attributed to U.S. parent companies. KSE’s full dataset lists hundreds of firms and dozens of seizure cases; roughly half of the documented write-offs occurred in 2022 with the rest spread through 2023–2025.

Although US corporations had the largest aggregate losses, a few corporations based in other countries had larger individual losses than the largest loss to any U.S. based corporations. For example, BP recorded a loss of $25.5 billion after divesting its stake in the Russian state-control oil company, Rosneft. Uniper, a Germa energy company, which Russia effectively nationalized, suffered a $22 billion loss. And Fortum, a Finnish energy company, whose Russian assets were nationalized, posted a $4.1 billion loss.

Reuters’ earlier compilation put total foreign losses from exits at about $107 billion at that time; KSE’s later aggregation is larger because it expands scope and updates corporate disclosures into early 2025. Use of multiple datasets helps triangulate the picture but explains differing totals.

Below are the better-documented U.S. cases and the sources used to quantify them:

- JPMorganChase—After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, JPMorganChase took a $1 billion write-down on its Russian assets and wound down its operations in Russia. These losses were concentrated in asset management and investment banking divisions. In 2024, Russian courts have ordered the seizure of JPMorganChase funds including $439.5 million and $155.8 million in separate lawsuits filed by Russian state-owned banks seeking to recover blocked funds held at JPMorganChase. JPMorganChase has countersued in U.S. courts to block these seizures.

- BlackRock— In March 2022, BlackRock investment funds suffered a $17 billion write-down on their holdings of Russian securities because the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent economic sanctions made Russian assets illiquid and unsellable. At the time, Russian assets constituted 0.18 percent of all assets in BlackRock investment funds. BlackRock suspended all purchases of Russian assets and began liquidating its Russian investment funds and distributing any liquid assets in these funds to shareholders.

- ExxonMobil—ExxonMobil suffered a $4 billion to $4.6 billion loss on its 30 percent investment in the Sakhalin-1 oil project off Sakhalin Island in Russia. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, ExxonMobil ceased operations in Russia and sought to sell its interest in Sakhalin-1. In October 2022, President Vladimir Putin blocked any voluntary sale and expropriated ExxonMobil’s interest in Sakhalin-1. According to press reports, ExxonMobil has engaged in secret talks with Russia’s state-owned oil company to re-enter the Russian market.

- McDonald’s—Prior to Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russian and Ukrainian operations produced 9 percent of McDonald’s global revenues and 3 percent of its net profits. After the invasion, McDonald’s ceased operations in Russia but continued to pay its employees until it sold its stores in Russia. In October 2022, McDonald’s record a loss of $1.2 to $1.4 billion on the sale of its Russian operations, most of which were company owned stores, to Russian investors.

- Starbucks— Prior to Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Starbucks had 130 licensed stores employing about 2,000 in Russia. Russian operations produced less than 1 percent of Starbucks’s global revenue. After the invasion, Starbucks ceased operations in Russia and took a pre-tax loss of $127 million in the first quarter of 2022.

- Ford—Ford was a 49 percent owner of a Sollers joint-venture in Russia. Because of a lack of profitability, Ford had been scaling back its Russian operations prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. In 2019, Ford had ceased making passenger vehicles in Russia and focused on producing commercial transit vans. In March 2022 after Russia’s invasion, Ford announced that it was suspended all operations, including manufacturing and parts supply, in Russia. In October 2022, Ford sold its stake in Sollers for a “nominal value” and recorded a $122 million loss. Ford retained a 5-year option to buy back its stake if conditions changed. The loss was small because Russia accounted for less than 0.5 percent of Ford’s global sales.

- Boeing—Boeing suffered losses from over 90 commercial jet orders from Russian airlines being placed in limbo and the seizure and confiscation of hundreds of leased Boeing jets by the Russian government. In response, Boeing ceased operations in Russia and the provision of parts, maintenance, and technical support to Russian airlines. Boeing also ceased purchasing titanium, a key material for airplane construction, from a Russian joint venture that Boeing had formed decades ago. In 2022, Boeing had a pre-tax charge of $212 million related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While Russia was a small share of Boeing’s global market, Boeing removed its forecast of 1,540 aircraft sales to Russia and central Asian countries valued at $200 billion through 2040 from its global forecast due to political uncertainty.

- Alphabet—In 2021, Russian operations produced 1 percent of Alphabet’s global revenues. In May 2022, the Russian government seized the bank accounts of Alphabet’s Google subsidiary in Russia. This seizure prevented the Russian subsidiary from paying suppliers, employees, and other financial obligations. As a result, the Russian subsidiary filed for bankruptcy. Russian courts have imposed ever increasing fines on Alphabet’s Russian subsidiary that now exceeds the world’s GDP for Alphabet’s failure to comply with content restrictions. Alphabet has suspended Google operations in Russia but some YouTube services are still available in Russia. Alphabet has not publicly declared its losses in Russia and are not consider a “material adverse effect” on the company as a whole.

- IBM—After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, IBM suspended its operations in Russia and recorded a loss of $300 million. In 2021, Russia had accounted for less than 1 percent of IBM’s global revenue.

- Whirlpool—After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Whirlpool recorded a loss of $300 million to $400 million on its sale of its factory in Lipetsk, Russia and its sales operations in Russia and CIS countries to a Turkish appliance maker, Arçelik AS, for $231 million that will be paid in installments over 10 years.

(These are representative U.S. cases; KSE’s annex and company filings list dozens of additional U.S. parent companies with smaller or less well-quantified losses.)

Important caveats and limits

- Different definitions / scope across sources. Reuters’ $107bn (March 2024) vs KSE’s $167bn (Feb-Mar 2025) difference shows how totals vary with cut-off dates, whether one counts announced impairments only or also seized asset valuations, and whether you count recovery proceeds from partial recoveries. Use KSE for the most recent consolidated cross-check.

- Non-cash vs cash losses. Many of the large numbers are non-cash accounting write-offs: they reduce equity/book value and reported earnings but may not immediately equate to cash outflows (the cash impact depends on whether assets were sold at a loss, seized outright, or whether profits were trapped). KSE attempts to capture both accounting write-offs and seized asset valuations where possible.

- Public disclosure gaps. Not every company gives a clear dollar figure in filings or press statements; in several U.S. cases the company disclosed an exit or suspension without a neat tabulated loss attributable to Russia. The table above therefore mixes quantified figures (where available) with documented exits/curtailments.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to economic sanctions and countermeasures. These events have been a major geopolitical shock that forced U.S. firms to reassess exposure to politically risky jurisdictions. For investors and corporate risk managers it is a reminder that political risk — sanctions, nationalizations, court orders, exit taxes and repatriation limits — can produce abrupt and significant loss of sales and write-offs even for very large companies.

Indeed, because write-offs are a way of measuring the magnitude of losses over time, those numbers are often much larger than the loss of exports in any given year. The bottom line is that the ongoing hostilities and associated trade restrictions are damaging to both the sales and value of American companies. All of which underscores the economic importance of achieving a peaceful settlement.

Conclusion

Peace between Russia and Ukraine is most important for humanitarian reasons, but there also would be significant economic benefits to both nations since wars cause resources to be misallocated to military uses. A fair end to hostilities (i.e., not rewarding Russian aggression) would leave more resources in the productive sector of the economy, where market forces would encourage them to be utilized in ways that satisfy consumer needs.

But peace would mean economic benefits for the rest of the world as well, particularly if the conflict ends in a way that leads nations to lift economic sanctions against Russia. That would enable an increase in cross-border trade, encouraging greater levels of efficiency and thus higher living standards.

The United States would be in a position to benefit from trade normalization with Russia and Ukraine. American exporters would be among the big winners since analysis based on pre-2014 trends suggest $20 billion-plus of additional sales.

Even more important, bad outcomes are averted if President Trump can achieve a fair peace. Having the dollar as the world’s reserve currency is very important for American prosperity. And having vibrant and competitive energy and aviation industries is similarly valuable for the U.S. economy.

Appendix I: Sanctions against Russia

The United States (US) uses economic sanctions to deter, change, or counter the malign actions and policies of the Russian Federation. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the US government maintains economic sanctions on Russia in coordination with the European Union (EU), the United Kingdom (UK), and other allied governments. In addition to the economic sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the US government imposes economic sanctions on the Russian Federation in response to or to deter cyber-attacks; human rights abuses and corruption; the use of a chemical weapon; the use of energy exports to coerce the governments of other countries; and weapons proliferation and illicit trade with Iran and North Korea. Even if Russia and Ukraine reach and implement a peace agreement that is acceptable to the US, the EU, and the UK, other economic sanctions against Russia are likely to remain and adversely affect trade and investment flows between Russia and the US.

Economic sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and other malign activities and policies are primarily authorized through two laws—the National Emergencies Act (NEA; PL 94-412; 50 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.) and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA; PL 95-223; 50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.) and implemented through a series of Executive Orders issued by Presidents Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden. In addition to economic sanctions that the President has implemented under these laws, Congress has enacted eight specific laws authorizing or mandating economic sanctions against Russia.

- Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-208, Title IV; 22 U.S.C. 5811 note)

- Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Ukraine Act of 2014, as amended (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95; 22 U.S.C. 8901 et seq.)

- Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014, as amended (UFSA; P.L. 113-272; 22 U.S.C. 8921 et seq.)

- Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017, as amended (CRIEEA; P.L. 115-44, Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act [CAATSA], Title II; 22 U.S.C. 9501 et seq.)

- Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act of 2019, as amended (PEESA; P.L. 116-92, Title LXXV; 22 U.S.C. 9526 note)

- Ending Importation of Russian Oil Act (P.L. 117-109; 22 U.S.C. 8923 note)

- Suspending Normal Trade Relations with Russia and Belarus Act (P.L. 117-110; 19 U.S.C. 2101 note)

- Russia and Belarus SDR Exchange Prohibition Act of 2022 (P.L. 117-185; 22 U.S.C. 8902 note)

- Annual appropriations for Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs

Economic sanctions against Russia (1) block assets and transactions with designated individuals and entities; (2) impose visa limitations and prohibitions on individuals; (3) restrict Russia’s central bank from drawing on its US dollar-denominated reserves; (4) bar new US investment in Russia and transactions in Russian sovereign debt; (5) restrict the importation of energy, gold, certain diamonds and minerals, and certain other goods from Russia; (6) ban the export of luxury goods and certain services to Russia; (7) impose export controls affecting Russian access to sensitive technologies; (8) raise tariffs on many imports from Russia; and (9) prohibit Russian use of US airspace and ports.

Many economic sanctions do not target the Russian government directly but instead designate specific individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN) of the Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) in the Department of the Treasury. Foreign individuals and entities on the SDN cannot access their US assets, and US individuals and entities cannot generally have transactions with foreign individuals and entities on the SDN. Moreover, the Secretary of State must deny entry into the United States and revokes visas of individuals on the SDN.

In addition to the SDN, economic sanctions may designate specific economic sectors or prohibit trade in certain goods and services. OFAC placed Russia’s defense, energy, and financial sectors on the Sectoral Sanctions Identifications List (SSI) or the Non-SDN Menu-Based Sanctions List (NS-MBS). Moreover, the Bureau of Industry of Security (BIS) in the Department of Commerce restricts exports to Russia to meet US treaty obligations to prevent the proliferation of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons and missile technology.

The EU, UK, Canada, and other US allies have imposed similar sanctions on Russia. Notably in 2022, the EU directed the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) and other financial messaging services to cease serving 10 Russian financial institutions.

The US government imposed many economic sanctions on Russia after its initial invasion of Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine in 2014. President Obama issued E.O.s 13660, 13661, 138662, and 13685. E.O. 13660 authorizes sanctions on anyone who undermined democracy and peace in Ukraine or invaded its sovereign territory. E.O. 13685 prohibits U.S. trade with and investment in occupied Crimea. E.O. 13661 authorizes sanctions against Russian government officials and those in the Russian arms industry. E.O. 13662 authorizes sanctions against sanctions against key sectors of the Russian economy as determined by the Secretary of the Treasury.

The US government imposed other economic sanctions on Russia after its invasion into the remainder of Ukraine in 2022. OFAC is implementing sanctions under the authority of E.O. 14024 issued by President Biden on April 15, 2021, and the expanded authority of E.O. 14114 issued by President Biden on December 22, 2022. E.O. 14024 imposes sanctions on those Russians who have engaged in “harmful foreign activities” and those Russians and their families operating in defense, technology, and related sectors of the Russian economy. OFAC applies E.O. 14024 to the financial services, aerospace, electronics, marine, accounting, trust and corporate formation services, management consulting, quantum computing, metals and mining, architecture, engineering, construction, manufacturing, and transportation. As amended by E.O. 14114, E.O. 14024 denies access to the U.S. financial system to foreign financial institutions that conduct significant transactions with designating persons operating in the technology, defense, construction, aerospace, and manufacturing industries or provide any significant services to Russia’s military-industry base.

In February and March 2022, President Biden issues four additional E.O.s:

- E.O. 14065 prohibits U.S. trade and investment with any area of Ukraine occupied by Russia and authorized sanctions against any entity operating there.

- E.O. 14066 prohibits imports of Russian oil, petroleum products, liquified natural gas, coal, and coal products and any US investment in Russia’s energy sector.

- E.O. 14068 prohibits imports of seafood, alcoholic beverages, and non-industrial diamonds from Russia into the United States and exports of luxury goods and US dollar-denominated banknotes. Subsequently, OFAC added Russian, gold, diamond jewelry, unsorted diamonds, aluminum, copper, and nickel to prohibited import list.

- E.O. 14071 prohibits new US investment in Russia and US services exports of accounting, trust and corporate formation, management services, quantum computing, architecture, engineering, and certain services related to metals exchanges and trading. OFAC added maritime transport of Russian crude oil, trading commodities, financing, shipping, insurance, flagging, and customs brokering.

OFAC has designated more than 4,500 individuals, entities, vessels, and aircrafts as SDNs. These designees include:

- President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin

- Other senior government officials and members of Russia’s legislature

- Regional governors and party officials

- Longtime friends and colleagues of Putin and executives of state-owned or state-controlled firms (known as the oligarchs). This includes 31 of 103 Russian billionaires.

- Entities in Russia’s defense, energy, financial services, metals and mining, technology, and transportation sectors. This includes 13 major Russian corporations and more than 275 of their subsidiaries.

- Foreign facilitators of sanction evasion in China, Cyprus, the Kyrgyz Republic, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates

- Individuals involved in the “research, development, production, and procurement” of drones

- Individuals involved with the transfer of munitions and ballistic missiles to North Korea

After the invasion of the rest of Ukraine in 2022, the BIS substantially tightened its export controls to defense, aerospace, and maritime sectors by subjecting Russia to the Foreign Direct Product Rules that prevent acquiring US goods and technology through third countries. BIS expanded export controls to oil refineries, luxury goods, commercial and private aircraft, goods intended for military modernization, software, construction materials, dual-use items, and machinery.

There are many other economic sanctions placed on Russia for its malign actions and policies that are unrelated to its invasion of Ukraine. These include:

- Malicious Cyber Actions. Issued by President Obama on April 1, 2015, E.O. 13694 initially addressed foreign cyber-attacks against critical U.S. infrastructure, for financial gain, or for disruption of computer networks. As amended by E.O. 13757, E.O. 13694 also addressed tampering with information with the purpose or effect of interfering with election processes or institutions. CRIEES, Section 224, enacted in August 2017, codified and expanded E.O. 13694. On September 12, 2018, President Trump issued E.O. 13484 authoring sanctions against foreign individuals or entities that have “directly or indirectly engaged in, sponsored, concealed, or otherwise been complicit in foreign interference in a United States election.” Under one or more of these orders, the United States has designated at least 76 individuals and related entities, vessels, or aircraft for activities interfering with US elections. Several of these individuals have been indicted by the Department of Justice.

- Arms Sales. OFAC imposed Section 231 sanctions on Russia for arms sales to China and Turkey. China’s Central Military Commission received 10 Su-35 combat aircraft in 2017 and S-400 surface-to-air missile system equipment in 2018. Turkey received S-400 surface-to-air missile system equipment.

- Human Rights Abuses and Corruption. In December 2012, President Obama signed into law the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012. This act authorized the President to impose sanctions on those involved in the criminal conspiracy that Magnitsky unearthed and those violating internationally recognized human rights of anyone fighting to expose the illegal activities of Russian officials or seeking to defend human rights in Russia. In December 2016, the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act was enacted. This act applied the sanctions under the Magnitsky Act globally. SSIDES as amended by CRIEEA in 2017 provides for sanctions on the commission of human rights abuses on any territory forcibly occupied by Russia. Moreover, Congress required the Secretary of State to deny entry into the United States of any Russian officials and their families involved in the corrupt exploitation of natural resources or gross human rights abuses. As of December 2023, 62 individuals and two entities were designated under the Magnitsky Act. Separately, the Department of the Treasury has imposed sanctions on 10 Russian officials responsible for Magnitsky’s death. Under the Global Magnitsky Act, OFAC has designated at least 21 Russian officials and entities.

- Use of a Chemical Weapon. The Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act of 1991 provides for sanctions against a government that has used a chemical weapon in violation of international law. On August 6, 2018, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo found that Russia had poisoned a British subject, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian intelligence officer, triggering the Act. In December 2018, OFAC imposed sanctions on two GRU officers for the attempted assassination of Skripal. In August 2019, President Trump ordered the Treasury to prevent US banks from lending to the Russian government or participating in the primary market for its bonds.

On March 2, 2021, Secretary of State Antony Blinken found that Russia had poisoned Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. The Department of State imposed sanctions on the FSB, GRU, two GRU officers, and three research institution for their role in the Navalny’s poisoning. On August 20, 2021, the Departments of State and the Treasury announced additional sanctions including US opposition to international loans to Russia, a prohibition on US banks from lending to the Russian government or participating in the primary market for its bonds, and presumed denial of export licenses to Russia for nuclear, chemical, biological, and missile-related goods and technology, and prohibition of arms and ammunition imports from Russia.

- Nord Stream 2. On its last day in office, the first Trump Administration imposed sanctions on Fortuna, which Gazprom employed to construct the Nord Strom 2 pipeline, under Sectio 232 of CFIEEA to sanction investors in and those who provide goods and services to Russian energy pipelines. In May 2021, the Biden Administration waived these sanctions.

- Other sanctions. The US government has imposed various other sanctions on Russia related to weapons proliferation, North Korea, Syria, and Venezuela. In addition, some Russian citizens are under sanction for their involvement with transnational crime and international terrorism.

Appendix II: Methodology

Trade data in this report are primarily from the World Trade Organization, specifically the WTO Stats website: https://stats.wto.org. Those numbers are generated from data supplied by statistical agencies in WTO members and are considered the most comprehensive data for any analysis of international trade. This report also utilizes data from the United States International Trade Commission at its USITC Data Web website: https://dataweb.usitc.gov.

The United States government also generates other trade data, such as the Commerce Department at its International Trade & Investment website: https://www.bea.gov/index.php/data/intl-trade-investment. These USITC and BEA sites provide detailed data on bilateral goods trade between the Russian Federation and the United States and between Ukraine and the United States, though those sites have much less information on trade in services.

The U.S. Trade Representative, https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements, is another bureaucracy involved with cross-border commerce, though its focus is on trade agreements and their enforcement.

These data sources are useful for the following types of information:

- BEA: Provides aggregate data on United States international goods and services trade flows, international investment flows, and international investment position.

- WTO: Provides aggregate and detailed data on international goods and service trade flows among all of its members, including the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and the United States.

- USITC: Provides detailed data on goods trade flows between the United States and other countries.

- USTR: Provides a detailed list of all trade agreements between the United States and other countries. Documents so-called unfair trading policies and practices of other countries.

In this study, goods trade and services trade generally are discussed separately. This is in keeping with international norms for trade analysis. If nations have high-quality systems of data collection, it is accurate and appropriate to add goods exports and services exports to generate total exports. Likewise, goods imports and services imports can be combined to measure total imports.

[1] “Exorbitant privilege,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exorbitant_privilege.

[2] Craig Anthony, Michael J Boyle, Kirsten Rohrs Schmitt, “10 Countries With the Most Natural Resources,” Investopedia, May 10, 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets-economy/090516/10-countries-most-natural-resources.asp.

[3] “Russia increases natural gas reserves to 67 trln cubic meters – Rosgeolfond,” Interfax, July 2, 2025, https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/112416/.

[4] “Russia’s natural gas reserves to last beyond 100 years,” February 10 , 2025, https://suezdaily.com/2025/02/10/russias-natural-gas-reserves-to-last-beyond-100-years/.

[5] Rosneft, “Rosneft and ExxonMobil to join forces in the Artic and Black Sea offshore, enhance co-operation through technology sharing and joint international projects,” Press Release, August 30, 2011, https://www.rosneft.com/press/releases/item/114495/.

[6] “Boeing Revenue 2011-2025 | BA,” macrotrends, https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/BA/boeing/revenue.

[7] “Boeing Backs America,” Boeing, https://www.boeing.com/useconomicimpact.

[8] Economic Freedom, Fraser Institute, https://efotw.org/economic-freedom/graph?geozone=world&countries=EST,POL,RUS,UKR&page=graph&area1=1&area2=1&area3=1&area4=1&area5=1&type=line&min-year=1970&max-year=2022.

“[9] GDP per capita (current US$) – Ukraine, Russian Federation, Estonia, Poland,” World Bank Group, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2024&locations=UA-RU-EE-PL&start=1987&view=chart.

[10] DATAWEB, United States International Trade Commission, https://dataweb.usitc.gov/.

[11] Mancur Olson, “The Rise and Delcine of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities,” Yale University Press, 1982, https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300254068/the-rise-and-decline-of-nations/.

[12] Nataliia Shapoval, Andrii Onopriienko, Oleksii Gribanovskiy, Nataliia Rybalko, “Assessing Foreign Companies’ Direct Losses in Russia: Financial Impact, Market Consequences, and Strategic Adjustments,” KSE Institute, February 2025, https://kse.ua/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/KSE_Assessing-Foreign-Companies-Losses-in-Russia.pdf.

[13] Alessandro Parodi, Alexander Marrow, “Foreign firms’ losses from exiting Russia top $107 billion,” Reuters, March 28, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/foreign-firms-losses-exiting-russia-top-107-billion-2024-03-28/.

———

Image credit: Dmytro Balkhovitin | CC BY-SA 4.0.