The Case for a Comprehensive Spending Cap

By Daniel J. Mitchell and Robert P. O’Quinn

The most effective budget reform that the United States could adopt to ensure its long-term prosperity is a spending cap. This document discusses why a spending cap is necessary and why it works better than a balanced budget requirement. This document examines the design of a spending cap. Finally, this document makes policy recommendations.

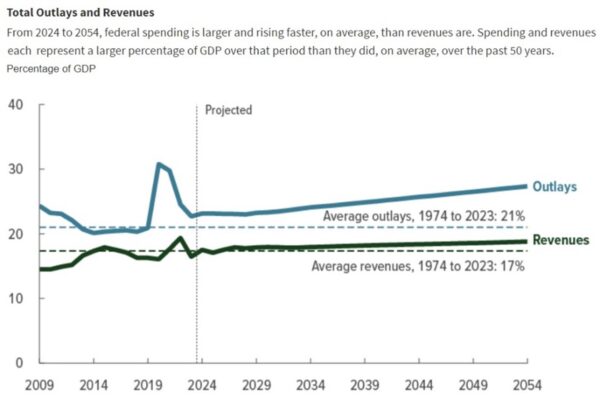

Congress should adopt a spending cap to shrink the burden of federal spending and avert a long-term fiscal crisis caused by demographics and existing entitlements. During fiscal year 2023, total federal outlays reached an all-time high of about $6.135trillion, which equaled 22.7 percent of GDP, and were 2.3 percentage points above their 60-year average.[1]

Although today’s federal budget numbers are grim, the real challenge will be in the future. Because of an aging population and poorly designed entitlement programs, the federal government will, in the absence of reform, become larger, redistributing ever greater amounts of national income. The long-run fiscal outlook of the United States is just as bad as it is in many European welfare states. The Congressional Budget Office projects the federal outlays will continue to absorb a larger share of GDP in the future.[2]

- By fiscal year 2034, total federal outlays will grow to $10.305 trillion, which will equal 24.9 percent of GDP.

- By fiscal year 2054, total federal outlays will explode to equal 27.3 percent of GDP.

- Increasing interest payments of the national debt, 3.1 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2024, will climb to 6.3 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2054.

- Spending for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and premium “tax credits” will expand by 3.4 percentage points over the next 30 years, from 10.7 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2024 to 14.1 percent of GDP in 2054.

- The remainder of the federal government—defense discretionary, domestic discretionary, and other entitlement programs—will shrink by 2.4 percentage points from an amount equal to 9.3 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2024 to an amount equal to 6.9 percent of GDP in 2054.

A rising burden of federal spending means ever-higher tax burdens and ever-larger amounts of government borrowing. A public sector that has grown too large is America’s main fiscal challenge. A rising tax burden and growing levels of red ink are symptoms of the underlying disease of big government.

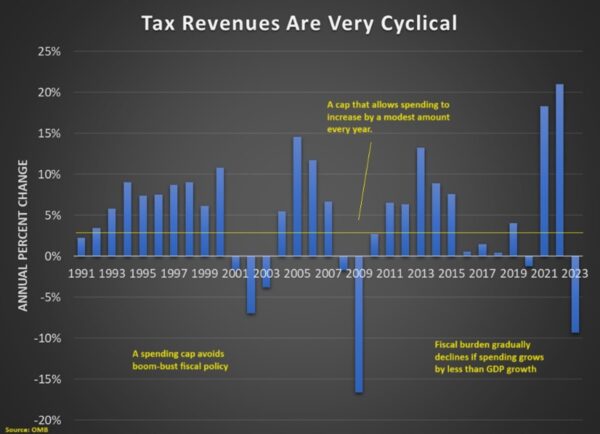

Figuring out how to restrain the growth of government spending is critically important. Fortunately, it shouldn’t be that difficult. Even if the economy is weak, nominal economic output will expand by an average of about 4 percent annually (meaning about 2 percent “real” GDP growth). And that means about 4 percent to 5 percent more tax revenue every year. It’s possible to slowly but surely control—and eventually shrink—the burden of federal spending if policymakers simply figure out some way to impose a spending cap so that outlays grow at a modest rate, say 2 percent annually.

Balanced Budget Rules Are Not Successful

When looking at rules to control federal spending, advocates of fiscal responsibility traditionally focused on some form of balanced budget amendment. A well-designed constitutional reform, restricting both red ink and the tax burden, would be a welcome change and could indirectly limit the size of the federal budget.

But why focus on the symptom of red ink rather than the underlying problem of excessive spending? Shouldn’t the real goal be to directly cap the growth of spending? Looking at the states, 49 out of 50 have some sort of balanced budget requirement. Those rules have not protected states such as California, Illinois, and New Jersey from either bloated public sectors or large levels of debt.

In the European Union, so-called Maastricht rules (also known as the Stability and Growth Pact) were imposed to prevent nations from having budget deficits of more than 3 percent of GDP and overall debt of more than 60 percent of GDP. These rules have not prevented unaffordable welfare states or rising levels of red ink in countries such as France, Italy, and Greece.

It might be possible to tighten these balanced budget rules and impose more effective restrictions on red ink, but that would be a major challenge, particularly in the United States. Constitutional reform here would require two-thirds support in both the House and Senate, followed by support from three-fourths of state legislatures.[3] Given the poor track record of rules that attempt to restrict deficits, it would be better to focus on rules that seek to directly address the real problem of excessive government spending.

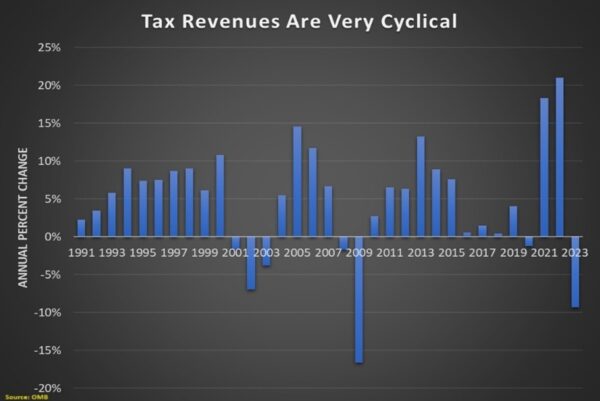

The Boom-Bust Cycle and Ratchet Effect

There’s a practical reason to focus on capping long-run spending rather than trying to balance the budget every year. Simply stated, the “business cycle” makes the latter very difficult. There are two major determinants of tax revenue. The obvious one is the overall tax rate, but the size of the economy (i.e., the tax base) is equally relevant. A weak economy won’t generate much additional tax revenue; a strong economy means that there are more wages to tax and more profits to tax. Thus, when a recession occurs and revenues drop, a balanced-budget mandate requires politicians to make dramatic changes at a time when they are especially reluctant to either raise taxes or impose spending restraint.

Then, when the economy is enjoying strong growth and producing lots of tax revenue, a balanced-budget requirement doesn’t impose much restraint on spending. All of which creates an unfortunate cycle. Politicians spend a lot of money during the good years, creating expectations of more and more money for various interest groups. When a recession occurs, the politicians suddenly must slam on the brakes. But even if they actually cut spending, it is rarely reduced to the level it was when the economy began its upswing.

Moreover, politicians often raise taxes as part of these efforts to comply with anti-deficit rules. When the recession ends and revenues begin to rise again, the process starts over—this time from a higher base of spending and with a bigger tax burden. Over the long run, these cycles create a ratchet effect, with the burden of government spending always reaching new plateaus.

Having some sort of rule to limit annual spending avoids the logistical problems of balanced-budget requirements. A spending cap tells politicians they can increase spending by, say, 2 percent when the economy is in recession. They like that better than a balanced-budget rule that would require actual cuts when revenue is dropping. But a spending cap also tells politicians they can increase spending by only 2 percent when the economy is growing quickly and revenues are rapidly increasing.

The challenge is to design an expenditure rule that works. There are many ways to design a spending cap, including reforms that would limit federal government spending to a certain share of overall economic output (18 percent of GDP, for instance). Scholars at the Mercatus Center have reviewed various rules and found that good results can be achieved with a simple approach that limits spending so that it grows no faster than the population plus inflation. The effectiveness of tax and expenditure limits (TELs) varies greatly depending on their design.

Effective TEL formulas limit spending to the sum of inflation plus population growth. This type of formula is associated with significantly less spending. TELs tend to be more effective when they require a supermajority vote to be overridden, are constitutionally codified, and automatically refund surpluses. These rules are also more effective when they limit spending rather than revenue and when they prohibit unfunded mandates on local government. Having one or more of these characteristics tends to lead to less spending.

Ineffective TELs are unfortunately the most common variety. TELs that tie state spending growth to growth in private income are associated with more spending in high-income states. Professor Michael New reached a similar conclusion, pointing out that the relatively strict limits in Colorado have been especially effective.

Why has Colorado’s [Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights] been more effective than other fiscal limits? . . . Colorado’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights . . . established a limit of inflation plus population growth. . . . [S]trong TELs have been able to restrict government growth. Holding other factors constant, strong TELs annually reduce growth in both state expenditures and state revenues by over $100 per capita.[4]

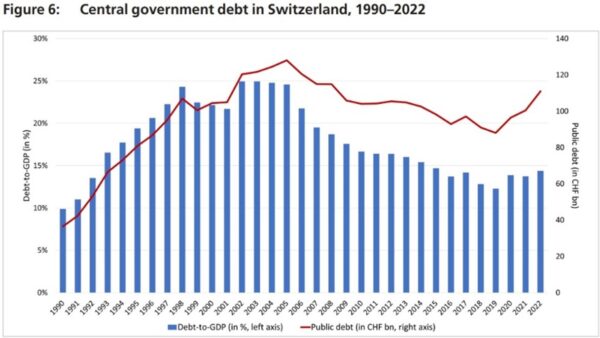

The Swiss “debt brake,” which functionally operates as a spending cap, has also been successful. It is described in a 2011 government report:

The Swiss “debt brake” or “debt containment rule” . . . combines the stabilizing properties of an expenditure rule (because of the cyclical adjustment) with the effective debt-controlling properties of a balanced budget rule. . . . The amount of annual federal government expenditures has a cap, which is calculated as a function of revenues and the position of the economy in the business cycle. It is thus aimed at keeping total federal government expenditures relatively independent of cyclical variations.[5]

One of the reasons the Swiss brake has been successful is that politicians are constrained from boosting spending during boom years when lots of tax revenue is generated. Here is another excerpt from the 2011 report.

The debt-to-GDP ratio of the Swiss federal Government has decreased since the implementation of the debt brake in 2003. …In the past, economic booms tended to contribute to an increase in spending… This has not been the case since the implementation of the fiscal rule, and budget surpluses have become commonplace. . . . The introduction of the debt brake has changed the budget process in such a way that the target for expenditures is defined at the beginning of the process, which must not exceed the ceiling provided by the fiscal rule. It has thus become a top-down process.

The Keynesian Case for Spending Caps

The underlying theory of Keynesian economics is that deficit spending should be increased during a recession to “prime the pump” of the economy. That theory doesn’t make much sense because the government can’t pour money into an economy unless it first borrows the money out of the economy. That being said, a spending cap should appeal to Keynesians because it allows federal outlays to increase even during recession years when revenue is falling. Since Keynesians (at least in theory) claim to support surpluses during boom years, they should like the fact that a spending cap limits spending during those periods, thus ensuring that rising revenues will be used to reduce red ink.

Real-World Evidence

The bad news is that few governments have imposed spending caps. The good news is that there have been very positive results when such policies are in effect. In Hong Kong, Article 107 of the Basic Law (the jurisdiction’s constitution) states, “The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall . . . keep the budget commensurate with the growth rate of its gross domestic product.” This sensible policy helps explain why total government spending averages less than 20 percent of GDP, significantly lower than the total burden of spending in America and far lower than in Europe’s welfare states.

In Switzerland, voters used a referendum in 2001 to impose the aforementioned debt brake, which operationally functions as a spending cap. Outlays have expanded by only about 2 percent annually since the constitutional reform was implemented. That restraint has led to a modest reduction in the burden of spending relative to GDP and a big reduction in government debt as a share of economic output.

Even International Bureaucracies Agree

Surprisingly, even organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have concluded that spending caps are the most effective type of fiscal rule. That development is rather remarkable given that these bureaucracies normally have a statist orientation on fiscal policy.

A 2022 study from the European Central Bank

…this paper provides an in-depth assessment of two alternative measures of fiscal consolidation and expansion: the change in the structural balance (dSB) and the expenditure benchmark (EB). Both the dSB and the EB are currently used to assess compliance with the fiscal rules under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). …The EB was introduced as an indicator in 2011, and has gained in importance relative to the dSB since the European Commission began to put more emphasis on it in 2016. …A comparison of the fiscal performance of euro area countries reveals significant differences depending on whether the assessment is based on the dSB or the EB. …this paper finds that the EB has advantages over the dSB as a fiscal performance indicator. …expenditure rules…provide more predictability in fiscal requirements. …Even more importantly, the EB can be shown to be less procyclical as a fiscal rule than the dSB.[6]

A 2019 study from the International Monetary Fund

In order to increase their chances of reelection, politicians are known to undertake fiscal manipulations, especially in election years. These fiscal manipulations typically take the form of increased public expenditure… Many countries, both developed and developing, have adopted fiscal rules in recent decades as an attempt to enforce fiscal discipline. …In this paper, we employ a cross-country panel dataset in order to test whether fiscal rules adopted in developing countries have been effective in constraining political budget cycles. …Our dependent variable is the general government’s final consumption expenditure as a share of GDP. … Our empirical evidence in a sample of 67 developing countries over the period 1985-2007, shows that fiscal rules cause fiscal discipline over the electoral cycle. More specifically, in election years with fiscal rules in place, public consumption is reduced by 1.65% point of GDP as compared to election years without these rules. Furthermore, the effectiveness of these rules depends on their type… In particular, expenditure rules, rules covering the general government and rules characterized by a monitoring body outside the government dampen political budget cycles in government consumption. …the results show that public consumption is reduced by 2.44% points during election years with expenditure rules in place. The findings on expenditure rules are consistent with Cordes et al. (2015) who show that the compliance rate for these rules are high.[7]

A 2015 study from the International Monetary Fund

In practice, expenditure rules typically take the form of a cap on nominal or real spending growth over the medium term (Figure 1). Expenditure rules are currently in place in 23 countries (11 in advanced and 12 in emerging economies). … Out of the 31 expenditure rules that have been introduced since 1985, 10 have already been abandoned either because the country has never complied with the rule or because fiscal consolidation was so successful that the government did not want to be restricted by the rule in good economic times. … In six of the 10 cases, the country did not comply with the rule in the year before giving it up. …In some countries, there was the perception that expenditure rules fulfilled their purpose. Following successful consolidations in Belgium, Canada, and the United States in the 1990s, these countries did not see the need to follow their national expenditure rules anymore. … Countries have complied with expenditure rules for more than two-third of the time. …expenditure rules have a better compliance record than budget balance and debt rules. …The higher compliance rate with expenditure rules is consistent with the fact that these rules are easy to monitor and that they immediately map into an enforceable mechanism—the annual budget itself. Besides, expenditure rules are most directly connected to instruments that the policymakers effectively control. By contrast, the budget balance, and even more so public debt, is more exposed to shocks, both positive and negative, out of the government’s control. … One of the desirable features of expenditure rules compared to other rules is that they are not only binding in bad but also in good economic times. The compliance rate in good economic times, defined as years with a negative change in the output gap, is at 72 percent almost the same as in bad economic times at 68 percent. In contrast to other fiscal rules, countries also have incentives to break an expenditure rule in periods of high economic growth with increasing spending pressures. … two design features are in particular associated with higher compliance rates. …compliance is higher if the government directly controls the expenditure target. …Specific ceilings have the best performance record. … The results illustrate that countries with expenditure rules, in addition to other rules, exhibit on average higher primary balances… Similarly, countries with expenditure rules also exhibit lower primary spending. …The data provide some evidence of possible implications for government size and efficiency. Event studies illustrate that the introduction of expenditure rules is indeed followed by smaller governments both in advanced and emerging countries.[8]

Another 2015 IMF study

An analysis of stability programs during 1999–2007 suggests that actual expenditure growth in euro area countries often exceeded the planned pace, in particular when there were unanticipated revenue increases. Countries were simply unable to save the extra revenues and build up fiscal buffers. …This reveals an important asymmetry: governments were often unable to preserve revenue windfalls and faced difficulties in restraining their expenditure in response to revenue shortfalls when consolidation was needed. …The 3 percent of GDP nominal deficit ceiling did not prevent countries from spending their revenue windfalls in the mid-2000s. … Under the SGP, noncompliance has been the rule rather than the exception. …The drawbacks of the nominal deficit ceiling are particularly apparent when the economy is booming, as it is compatible with very large structural deficits. … The initial Pact only included three supranational rules… As of 2014, fiscal aggregates are tied by an intricate set of constraints…government spending (net of new revenue measures) is constrained to grow in line with trend GDP. …the expenditure growth ceiling may seem the most appealing. This indicator is tractable (directly constraining the budget), easy to communicate to the public, and conceptually sound… Based on simulations, Debrun and others (2008) show that an expenditure growth rule with a debt feedback ensures a better convergence towards the debt objective, while allowing greater flexibility in response to shocks. IMF (2012) demonstrates the good performance of the expenditure growth ceiling.[9]

A 2015 study from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

It is understandable that citizens ask why public financial management processes did not guard, in a more effective way, against the vagaries of the economic cycle…the OECD’s recent Recommendation on Budgetary Governance…spells out a number of simple, clear yet ambitious principles for how countries should manage their budgets and fiscal policy processes. …the most salient lesson…is not to seek to avoid altogether the fiscal shocks and cyclical downturns, to which our economies are subject from time to time. The real challenge is to build resilience into our national framework…to mitigate these fiscal shocks. …As to fiscal resilience, this report underpins the wisdom of…fiscal rules. … The European Union’s Stability and Growth Pact…proved largely ineffective in protecting countries from the effects of the fiscal crisis. …Simple and clear fiscal anchors – e.g., the Swiss and German debt brake rules – appear to have been more effective in influencing effective fiscal management. … Switzerland’s “debt brake” constitutional rule has proven a model for some OECD countries, notably Germany. …Germany adopted a debt brake rule in 2009… In addition, the United Kingdom recently announced (June 2015) its plan… Furthermore,…it is preferable to combine a budget balance rule with an expenditure rule.[10]

Another 2015 OECD report

A combination of a budget balance rule and an expenditure rule seems to suit most countries well. …well-designed expenditure rules appear decisive to ensure the effectiveness of a budget balance rule and can foster long-term growth. …Spending rules entail no trade-off between minimising recession risks and minimising debt uncertainties. They can boost potential growth and hence reduce the recession risk without any adverse effect on debt. Indeed, estimations show that public spending restraint is associated with higher potential growth.[11]

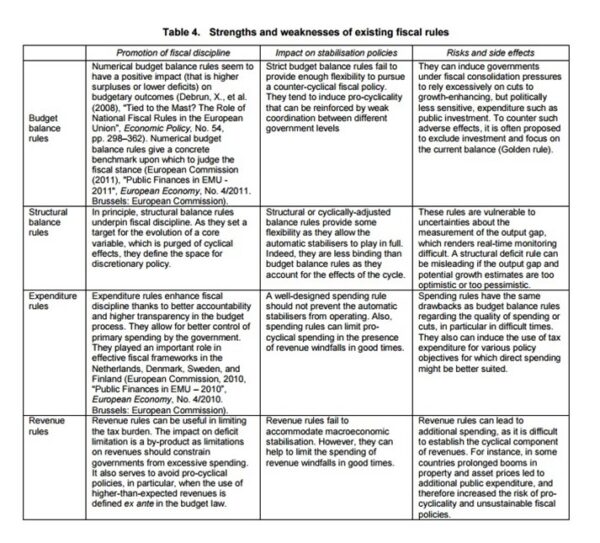

Here’s a table from that report that summarizes the pluses and minuses of different fiscal rules.

A 2015 European Central Bank Report

…during a boom phase fiscal rules do not prevent fiscal policy from turning expansionary, while at times of a recession fiscal policy is potentially restrictive as governments need to comply with the rules’ requirements. This effect is assumed to be particularly pronounced in periods of limited fiscal space, while it might be less obvious in an environment of high fiscal space. … We find strong evidence for fiscal rules being associated with higher fiscal space, i.e. the fiscal room for manoeuvre is higher in those countries which have established fiscal rules. This may not be surprising as fiscal rules are implemented to keep primary balances under control… When splitting the results by different types of fiscal rules, we find significant coefficients for expenditure and, to a lesser extent, balanced budget rules, but none for debt rules. … Regarding the different types of fiscal rules, we find particularly strong coefficients for expenditure rules, possibly reflecting the fact that expenditure rules are easier to monitor and are thereby more credible. …If a country had a fiscal rule in place for the past ten years the average fiscal space for those years is around 22% of GDP higher. The coefficient is proportional to the number of years in which a fiscal rule has been in place. … …if governments have fiscal rules in place, the results suggest that governments can no longer fully use their fiscal space and (on average) are even forced to reduce their current expenditures. … balanced budget rules…and expenditure rules…are correlated with a lower coefficient for fiscal space on procyclicality. This is in line with our findings above that expenditure rules might restrict discretionary expenditures.[12]

When even the IMF and OECD agree that spending caps are effective, that’s a remarkable sign that all other options do not work. But there really wasn’t any other possible conclusion. Requirements for balanced budgets in 49 out of 50 states haven’t prevented wasteful spending and more debt. Maastricht anti-deficit and anti-debt rules in the European Union haven’t blocked bloated welfare states and fiscal crisis.

There’s also academic evidence for spending caps. In 2023, the Swiss Federal Finance Administration published a study on fiscal rules. Authored by Thomas Brändle and Marc Elsener, it summarized some of the recent research.

A rich empirical literature investigates the impact of fiscal rules. First, the focus is on surveying recent studies that investigate the relationship between fiscal rules and “traditional” fiscal performance measures, such as public debt and budget balances. …For EU countries and the period 1990-2012, Nerlich and Reuter (2013)…find that the introduction of fiscal rules is related to lower public expenditures as well as to lower revenues. As the impact on revenues is smaller, the primary balance improves. This impact is stronger when fiscal rules are enacted in law or constitution and supported by independent fiscal institutions and effective medium-term expenditure frameworks. Fiscal rules have the strongest limiting impact on social spending, compensation of public employees. …Based on a panel of 30 OECD countries, Fall et al. (2015) find that fiscal rules are related to improved fiscal performance. In particular, a budget balance rule appears to have a positive and significant effect on the primary balance and a negative and significant effect on public spending. Expenditure rules are associated with lower expenditure volatility and higher public investment efficiency. …Focusing on expenditure rules, Cordes et al. (2015) present an analysis for 29 advanced and developing countries for the period 1985–2013. Using a dynamic panel estimation approach, the analysis shows that these rules are associated with better spending control…and improved fiscal discipline. …Asatryan et al. (2018) study whether constitutional-level fiscal rules – expected to be more binding – impact fiscal outcomes. …they find that the introduction of a constitutional balance budget rule leads to a lower probability of sovereign debt crisis. For their most preferred sample of 132 countries between 1945 and 2015, they find that the debt-to-GDP ratio decreases by around 11 percentage points on average with constitutional balance budget rules. Most of these consolidations are explained by decreasing expenditures rather than increasing tax revenues.[13]

Spending caps are simple and easy to understand, and they directly address the real problem of excessive spending. And in the few places they’ve been tried, the evidence shows that dealing with the underlying disease of too much government automatically fixes the symptom of red ink. The United States could avert a very bad long-run fiscal crisis by copying the wise policies of Switzerland and Hong Kong.

Designing a Spending Cap for America

Designing a spending cap requires two major decisions. First, what spending should be capped. Second, how should it be capped.

Spending caps may be based on (1) total federal outlays or (2) primary federal outlays. Total federal outlays are the entire federal budget, including discretionary outlays, mandatory outlays, and net interest outlays. Primary outlays are the entire budget minus net interest outlays. The current Congress can control discretionary outlays through appropriations acts and mandatory spending through amendments to authorization acts. However, the current Congress cannot control net interest outlays because (1) the level of federal debt held by the public was determined by the spending and taxing decisions of previous Congresses, and (2) interest rates are determined by general economic conditions and the monetary policy decisions of the Federal Reserve.

While a spending cap should control total federal outlays over the long term, an annual spending cap based on total federal outlays may have unintended negative consequences. During a fiscal year, an accommodative monetary policy will lower interest rates, reduce net interest costs, and allow a higher level of primary federal spending, while a restrictive monetary policy will raise interest rates, increase net interest outlays, and force a lower level of primary federal spending. In any fiscal year, however, a spending cap based on total federal outlays creates a perverse incentive for the President and Members of Congress to press the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates regardless of economic conditions to enable higher primary federal spending. The likely result of this perverse incentive is a high rate of price inflation over the medium term.

A spending cap based on primary federal spending has several advantages over a spending cap bases on total federal outlays. First, a spending cap based on primary federal spending holds the current Congress responsible for what it can control—discretionary and mandatory outlays—through changes in law and not for what it cannot control—net interest outlays during the current fiscal year. Second, a spending cap based on primary federal spending protects the independence of the Federal Reserve to pursue a monetary policy consistent with price stability. Third, a spending cap based on primary federal spending is likely to produce a smoother glidepath for reducing federal outlays over time. Fourth, a spending cap based on primary federal spending will control total federal outlays over time as annual additions to federal debt held by the public gradually diminish and the size of federal debt held by the public as a percent of GDP begins to fall. Therefore, we recommend a spending cap based on primary federal outlays.

The next decision is how to cap primary federal outlays. There are two methods—a growth rate cap and a level cap. A growth rate cap restricts the growth of primary federal outlays from one fiscal year to the next and is usually expressed as the inflation rate plus population growth. A level cap restricts primary federal outlays relative to some measure of national income and is usually expressed as a percent of GDP.

Both methods have strengths and weaknesses. A growth cap of the inflation rate and population growth is easy to understand. Over time, a growth cap of the inflation rate and population growth will cause primary federal outlays as a percentage of GDP to decline as real GDP per capita increases. This ratcheting down of primary federal outlays relative to GDP is simultaneously a strength and a weakness of a growth cap. Over time, ratcheting down will reduce the size of the federal government relative to the private sector, but endless ratcheting down may at some future point undermine public support for a growth cap and lead to its repeal. A growth cap of the inflation rate and population growth is immune from the business cycle by disallowing both rapid growth of primary federal outlays during a boom and then forcing a sharp slowdown or even a contraction of primary federal outlays during a recession.

A fixed level cap holds primary federal outlays constant as a percentage of GDP. Because a fixed level cap does not endlessly ratchet down primary federal outlays as a percent of GDP, a fixed level cap may be more politically sustainable over time than a growth rate cap. However, a fixed level cap that uses GDP as its denominator causes the growth rate of primary federal outlays to vary with the business cycle, expanding rapidly in boom fiscal years and slowing abruptly or even contracting in recession fiscal years. Such a pro-cyclical fluctuation in the growth rate of primary federal outlays is neither economically desirable nor politically sustainable.

Proponents of a fixed level caps have proposed various modifications to address the business cycle problem. These include: (1) a provision that the cap amount in a fiscal year cannot be less than the cap in the previous fiscal year, (2) an automatic suspension of the cap in any fiscal year when a recession occurs, and (3) the use of a rolling five-year average of GDP as the denominator. These modifications do not solve the business cycle problem. First, the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research does not decide the official peak or trough of a business cycle in the United States until months or in some cases more than a year after it occurs. Second, a denominator using a five fiscal year rolling average of GDP is still affected if a recession occurred in any of the five fiscal years. Fortunately, former Chair of the Committee on Ways and Means in the U.S. House of Representatives Kevin Brady proposed the best solution to the business cycle problem with a fixed level cap—using potential GDP rather than actual GDP as the cap’s denominator. Potential GDP is the calculation of what GDP would be under conditions of price stability and full employment—the economic sweet spot. Therefore, potential GDP is not affected by the business cycle. Therefore, any fixed level spending cap should be based on primary federal spending as a percent of potential GDP.

Given the high current level of primary federal outlays as a percent of GDP relative to their historical average and the CBO projections that primary federal outlays as a percent of GDP will increase for the foreseeable future if spending policies do not change, a ratcheting down of primary federal spending for several fiscal years is necessary. Thus, a growth rate cap is desirable in the medium term. However, ratcheting down cannot continue indefinitely as it will eventually undermine public support for a growth rate cap leading to its repeal. When primary federal outlays fall below a pre-determined threshold, a fixed level cap should replace the growth rate cap.

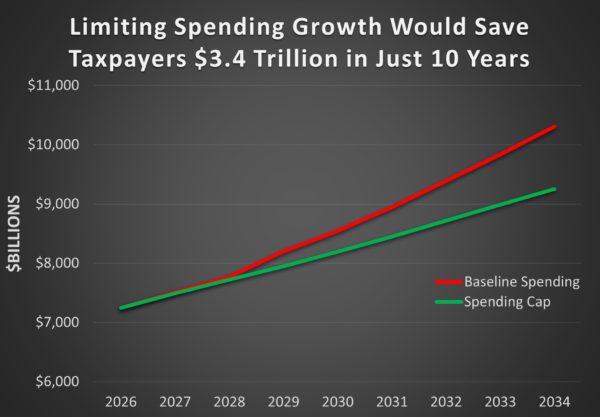

Based on these considerations, we propose an initial growth cap of the annual inflation rate as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Index and the annual change in U.S. population excluding people not legally present as determined the U.S. Bureau of the Census. Once primary federal outlays decline to 17 percent or less of potential GDP, the growth cap will be replaced by a fixed level cap of 17 percent of potential GDP. The chart shows how such a cap would save money over the first 10 years of its existence.

Ideally, a spending cap would be implemented by a constitutional amendment. However, we realize a constitutional amendment imposing a spending cap would be highly unlikely to be ratified. Therefore, we anticipate Congress would enact our spending cap by statue. A statutory spending cap raises the enforcement and sustainability issue since Congress can easily repeal a statutory spending cap.

The first design decision for enforcing a statutory spending cap is how strict the enforcement mechanism should be—should the enforcement provision require a sequestration that achieves the annual spending cap regardless of how deep the sequestration is and how politically sustainable such sequestration may be, or should the enforcement provision reduce primary federal outlays in a way that is politically sustainable but not necessarily enough to achieve the annual spending cap in a particular fiscal year. The second design decision is whether the sequestration should be broad-based and include popular entitlement problems such as Social Security and Medicare or should be limited to specific programs.

Sequestration under Gramm-Rudman was poorly designed because large portions of primary federal outlays were entirely exempt from sequestration while sequestration fell on only a small portion of primary federal outlays. Sequestration under Gramm-Rudman was designed to achieve fixed federal budget deficit targets no matter how large sequestration would be. We believe that Gramm-Rudman was repealed when sequestration on specific programs became too large for the public to bear.

Our sequestration is fundamentally different. All primary federal outlays are subject to sequestration, but the amount of sequestration for any program would be limited in size. If Congress fails to adhere to our spending caps, (1) all discretionary programs would be frozen at their level in the previous fiscal year, (2) all cost-of-living adjustments in Social Security and other cash entitlement programs would be deferred until Congress brings primary federal outlays within the spending cap, (3) all inflation adjustments in provider payments for Medicare would be deferred until Congress brings primary federal outlays within the spending cap, (4) all Medicaid payments to states and territories would be frozen at their level in the previous fiscal year, (5) defer any inflation adjustment to the thrifty food plan and the eligibility standards for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Plan (SNAP, formerly known as Food Stamps) and to subsidies for Child Nutrition Programs, and (6) defer any inflation adjustments in the eligibility standards for the Earned Income Tax Credit and the refundable portion of the Child Tax Credit We believe our sequestration will produce politically sustainable reductions in primary federal outlays in any fiscal year that continue to rachet down primary federal outlays over the medium term.

Another design decision is how to deal with additional outlays due to war or natural disasters. One option is an automatic waiver. Another option is a Congressionally approved waiver. However, a waiver would allow additional outlays not only related to war or natural disasters but also to other programs domestic or international.

We reject the waiver and instead proposed the following two exceptions. First, as the United States is a large and geographically diverse country, a natural disaster is likely to occur somewhere within its borders in any given year. Therefore, we propose that 2 percent of the total primary federal outlays allowed under the spending cap in any fiscal year be set aside for outlays related to natural disasters or other unforeseen emergences during the fiscal year. If at the end of a fiscal year, any portion of the amount set aside for natural disasters or other unforeseen emergences that has not been appropriated may be used either (1) to provide a tax rebate to individual federal income taxpayers in proportion to the federal income taxes that the taxpayers paid in the previous calendar year, or (2) reduce the outstanding federal debt held by the public.

Second, for any fiscal year in which a declaration of war in effect or Congress has otherwise authorized U.S. armed forces to engage in ongoing combat, Congress may raise the spending cap by an amount equal to the difference between actual national defense outlays and what national defense outlays would have been in absence of a declaration of war or a Congressional approval for combat. This provision would allow Congress to appropriate whatever is necessary to win a war or succeed in combat but would prevent Congress from piggybacking other additional outlays for unrelated programs into an approval for necessary additional national defense outlays.

Finally, we believe the President should submit an annual budget that complies with spending caps before the beginning of a fiscal year. We cannot prohibit a President from proposing new programs, additional federal outlays, increasing the spending cap, or repealing it altogether. If a President wishes to do so, he should be able to submit an alternative annual budget that does not comply with the spending caps as well as an annual budget that does.

Conclusion

The United States has a very serious long-run fiscal problem. The burden of government spending is on an upward trajectory. At best, this means the United States becomes a European-style welfare state, which means anemic economic performance and a stifling tax burden on lower-income and middle-class households. But it’s also likely that ever-growing government will be accompanied by ever-growing levels of government debt. And that could lead to a Greek-style fiscal crisis and threaten the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency. A spending cap could avert these unpleasant outcomes by imposing some long-overdue spending restraint on Washington.

[1] “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034,” Congressional Budget Office, June 18, 2024. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60039

[2] “The Long-Term Budget Outlook: 2024 to 2054,” Congressional Budget Office, March 20, 2024. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60127

[3] Or the support of special ratification conventions in three-fourths of the states.

[4] Michael J. New, “U.S. State Tax and Expenditure Limitations: A Comparative Political Analysis,” State Politics & Policy Quarterly, Volume 10, Issue 1, March 1, 2010. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/153244001001000102

[5] Alain Geier, “The Debt brake – the Swiss fiscal rule at the federal level,” Federal Finance Administration, Working Paper of the FFA No 15, February 2011. https://www.efv.admin.ch/dam/efv/de/dokumente/publikationen/grundlagenarbeiten-wirtschaftspolitik/schuldenbremse/grundlagen/working-paper-15-e.pdf.download.pdf/working-paper-15-e.pdf

[6] Nicholai Benalal, Maximilian Freier, Wim Melyn, Stefan Van Parys, Lukas Reiss, “Towards a single performance indicator in the EU’s fiscal governance framework,” European Central Bank, No 288, January 2022. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op288~b3b265ed14.en.pdf?5c3d09a20c873728f932e34e47db856f

[7] Kodjovi Eklou, Marcelin Joanis, “Do Fiscal Rules Cause Fiscal Discipline Over the Electoral Cycle?” IMF Working Paper No. 19/291, December 2019. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3524311

[8] Till Cordes, Tidiane Kinda, Priscilla Muthoora, and Anke Weber, “Expenditure Rules: Effective Tools for Sound Fiscal Policy?” IMF Working Paper No. 15/29, February 2015. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2015/wp1529.pdf

[9] Luc Eyraud, Tao Wu, “Playing by the Rules: Reforming Fiscal Governance in Europe,” IMF Working Paper No. 15/67, April 14, 2015. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2594151

[10] “The State of Public Finances 2015: Strategies for Budgetary Consolidation and Reform in OECD Countries,” OECD, 2015. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/the-state-of-public-finances-2015_9789264244290-en

[11] Falilou Fall, Debra Bloch, Jean-Marc Fournier, and Peter Hoeller, “Prudent debt targets and fiscal frameworks,” OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 15. July 1, 2015. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/prudent-debt-targets-and-fiscal-frameworks_5jrxtjmmt9f7-en

[12] Carolin Nerlich and Wolf Heinrich Reuter, “Fiscal rules, fiscal space and procyclical fiscal policy,” European Central Bank, Working Paper Series, No 1872, December 2015. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1872.en.pdf

[13] Thomas Brändle, Marc Elsener, “Do fiscal rules matter? A survey on recent evidence,” Federal Finance Administration, FFA Working Paper No. 26, September 2023. https://www.newsd.admin.ch/newsd/message/attachments/82382.pdf