There are three reasons to be a knee-jerk supporter of tax cuts (or to be a knee-jerk opponent of tax increases).

- The morality-driven libertarian argument that people should be able to keep the income they earn.

- The starve-the-beast argument that less revenue at some point may translate into less spending.

- The economic argument that lower taxes lead to better economic performance and more growth.

Today, let’s focus on the third argument.

To elaborate, lower taxes generally are good for growth, but not all tax cuts are created equal.

Some tax cuts (lower marginal tax rates on high earners, lower capital gains tax rates, lower corporate tax rates, etc) can be very powerful because affected taxpayers have a lot of control over the timing, level, and composition of their income. So if their tax rates change, they have the incentive and ability to increase their economic activity.

Other tax cuts (child credits, lower sales taxes, etc) may not have much economic impact because there is no significant change in incentives to work, save, invest, or be entrepreneurial. Or maybe taxpayers don’t simply don’t have much flexibility to respond. For instance, I’m a regular wage earner so I don’t have much ability or incentive to change my economic activity if my tax rate changes.

Understanding the economics of taxation is important because major parts of the Trump tax cuts will expire at the end of next year and it is very likely that politicians in Washington soon will decide that only some parts are worth keeping.

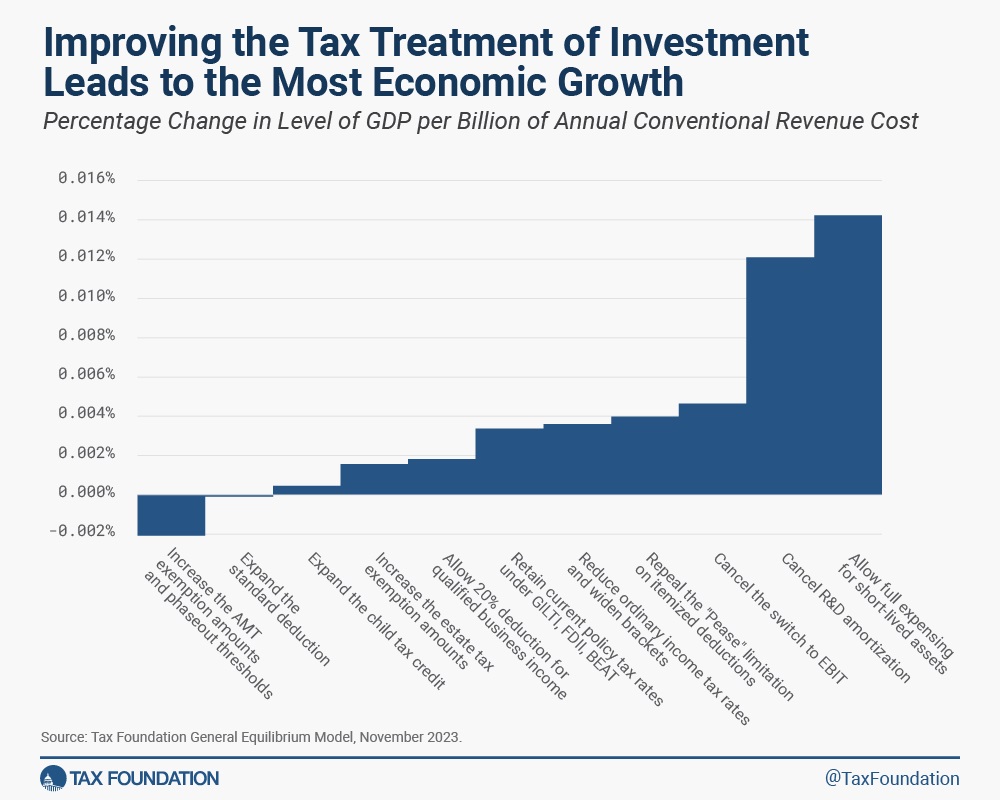

But which of the expiring tax cuts should be preserved? Here’s a chart showing how much “bang for the buck” the economy gets from different parts of the Trump tax cuts.

The chart comes from some new research by Erica York of the Tax Foundation. Here’s some of what she wrote.

…most of the 2017 tax reform law will expire after the end of next year. If lawmakers allow full expiration to occur, most Americans will see their personal tax bills rise and incentives for working and investing worsen. Extending the entire tax reform, however, would come with a $3.7 trillion price tag at a time when the country’s fiscal outlook is already bleak. Lawmakers should…prioritize policies that best boost work and investment incentives in a fiscally responsible manner. …The 11 tax cuts vary widely in how they would affect people’s decisions to work and invest. Some tax cuts create a larger economic boost than others. One indicator is to compare the estimated change in long-run GDP to the estimated change in annual tax revenue in the final year of the budget window. Using the last year of revenue is a proxy for the ongoing, long-run cost of a policy change. The most powerful provision under that metric is full expensing for business investment in equipment, followed by expensing for research and development costs. At the other end, some tax cuts counterintuitively reduce economic output because of their interactive effects with marginal tax rates. Other tax cuts have middling effects, improving incentives to work or invest but not as powerfully as full expensing.

None of this means that you have to agree with the exact details of the Tax Foundation’s model, or that economic bang for the buck should be the only consideration when deciding tax policy.

That being said, I think the Tax Foundation’s model is based on sound economic principles and that pro-growth tax cuts are important if the goal is to maximize long-run income for average households.

———

Image credit: N i c o l a | CC BY 2.0.