Last year, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) released an online budget game called “Fix the National Debt.”

I would have preferred a game called “Reduce the Size of the Federal Government,” since that would have put the focus on the real problem.

But I dutifully answered all the questions, got my results, and then had two big complaints.

- There were not nearly enough options to restrain and/or cut spending and zero options for shutting down departments (such as Education, Energy, HUD, Agriculture, and Transportation).

- There was no data on what happens to the burden of government spending as a share of GDP, which is a more important indicator of good policy than what happens to debt as a share of GDP).

We now have a 2024 version of the CRFB game.

Unfortunately, it still focuses on the symptom of red ink rather than the real problem of excessive spending.

But I can’t resist this kind of budget exercise. So, once again, I went through all the options and picked the reforms that would be good policy.

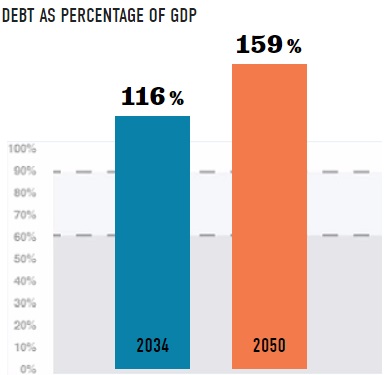

Here’s CRFB’s starting point.

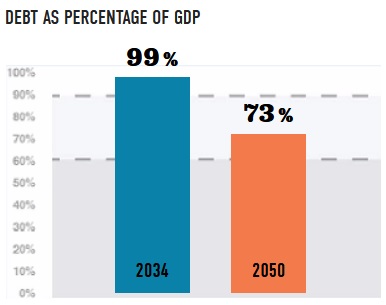

And here are the debt levels based on my choices.

Since CRFB wants lower levels of debt, both by 2034 and 2050, I supposedly failed.

But the criticisms I made last year still apply. If more options had existed to reduce or eliminate counterproductive programs, I easily would have reached CRFB’s debt benchmarks.

More important, I would have substantially reduced the burden of government spending, thus allowing much greater prosperity.

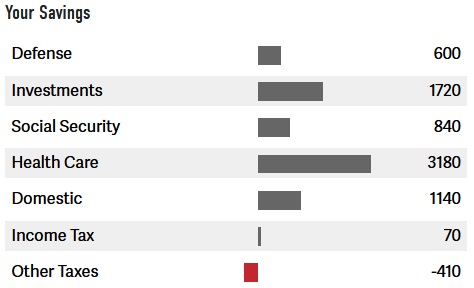

By the way, here’s the breakdown of my choices. I had a small net tax cut and opted for just about every possible spending cut (keep in mind that CRFB uses the dodgy Washington definition of a budget cut).

I’ll make two final observations.

First, the “investments” category deals with spending on education and infrastructure. Since the federal government has a horrible track record in those areas, such spending is more accurately characterized as “mal-investments.”

Second, the CRFB game assumes that fiscal policy has no impact on the economy. You get zero credit even if you dramatically reduce the burden of taxes and spending. Likewise, there’s no penalty for people who choose more spending and higher tax burdens.

At the risk of understatement, that grossly unrealistic.

Then again, CRFB would probably choose an inaccurate feedback mechanism (based on levels of red ink), so maybe it’s good they don’t have any economic assumptions.