Federal Spending Primer, Part I: Budget Basics

By Robert P. O’Quinn*

This primer explains the core features of federal budgeting. The first section defines key concepts related to spending, revenue, loans, and debt. The second section describes the budget process for both the executive and legislative branches. Budgetary data for fiscal year 2022 and four appendices follow.

Budget Concepts

FEDERAL SPENDING. In fiscal year 2022, federal outlays were $6.273 trillion. For budgetary purposes, there are three types of federal spending – discretionary outlays, mandatory outlays, and net interest outlays. Tables 1-1 summarizes federal outlays for fiscal year 2022 per the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

- Discretionary outlays. In fiscal year 2022, discretionary outlays were $1.664 trillion. Discretionary spending includes (1) national defense;[1] (2) international affairs;[2] (3) non-entitlement, non-guaranty domestic programs, and (4) the administrative costs of federal entitlement programs such as Social Security. To fund discretionary spending, Congress enacts appropriations legislation[3] that creates specific budget authority that allows federal departments and agencies to incur financial obligations[4] to implement authorized programs and allows the Treasury make outlays to pay such financial obligations.[5] Appropriations legislation provides budget authority for a specific time—usually a fiscal year.[6] Table 1-2 summarizes discretionary outlays for fiscal year 2022 per OMB.

- Mandatory outlays. In fiscal year 2022, mandatory outlays were $4.368 trillion. Mandatory spending includes (1) benefits from federal entitlement programs such as Social Security;[7] (2) federal guaranty programs such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), and (3) the salaries of the President, the Vice President, Members of Congress, Supreme Court Justices, and other federal Judges. To fund mandatory spending, Congress enacts authorization laws that permanently appropriate “such sums as may be necessary.”[8] Table 1-3 summarizes mandatory outlays for fiscal year 2022 per OMB.

- Net interest outlays. In fiscal year 2022, net interest outlays were $476 billion. Net interest outlays are the interest payments made by Treasury to the owners of federal debt held by the public minus interest and dividend payments received by the Treasury.[9]

FEDERAL REVENUE. In fiscal year 2022, federal receipts were $4.897 trillion. For budgetary purposes, there are two types of payments to the federal government—federal receipts and offsetting collections and offsetting receipts.

- Federal receipts are involuntary payments that the Treasury collects. Federal taxes are the principal source of federal receipts. In descending order of importance, there are:

- Individual income tax is levied on the income of individuals, sole proprietorships, partnerships, and small- and medium-sized corporations.

- Social insurance taxes (payroll taxes) are levied on the wages and salaries earned by employees and the earnings of the self-employed. Payroll taxes fund Social Security and a portion of Medicare.

- Corporate income tax is levied on the income of large corporations.

- Excise taxes are levied on certain goods and services with receipts often dedicated to fund certain programs. The federal gasoline tax is an example of this type of levy.

- Customs duties are levied on imports.

- Estate and gift taxes are levied on the estate of deceased individuals and large transfers between individuals.

Other sources of federal receipts include the excess profits of the Federal Reserve, fees, and fines. Table 1-4 summaries federal receipts for fiscal year 2022 per OMB.

- Offsetting collections and offsetting receipts are voluntary payments that the Treasury collects in exchange for the purchase of goods and services from the federal government.[10] Strangely, these receipts are counted as negative spending.[11]

BUDGETARY TREATMENT OF FEDERAL DIRECT LOANS AND FEDERAL LOAN GUARANTIES. At the end of fiscal year 2022, there were $2.071 trillion in federal direct loans outstanding and $2.898 trillion in federal loan guaranties outstanding. Loan disbursements and repayments, loan guaranty default payments, fees, and default recoveries are not included in federal outlays and offsetting collections and receipts. Instead, government agencies record the subsidy costs of federal direct loans or federal loan guaranties as budgetary outlays in credit program accounts up front when such loans or guaranties are made. The subsidy cost is the estimated present value of expected payments to and from the public over the duration of a loan or guaranty discounted by the appropriate Treasury interest rate. Simultaneously, government agencies make non-budgetary outlays equal to the subsidy costs to separate non-budgetary financing accounts that record (1) all transactions with the public including loan disbursements and repayments, loan guaranty default payments, fees, and recoveries on defaults; and (2) all transactions with the Treasury necessary to finance such loans and guaranties. If law or administrative action reduces or eliminates the obligations of borrowers, government agencies must record such increases in subsidy costs as budgetary outlays in the agency’s credit program account. See Table 1-5 for federal direct loans outstanding and federal loan guaranties outstanding at the end of fiscal year 2022.[12]

BUDGET SURPLUS AND DEFICIT. When federal spending is greater than federal revenue, there is a budget deficit, meaning the Treasury Department must borrow from the private sector (both domestic and foreign) and foreign governments to finance a portion of the budget.[13] If federal revenues are greater than federal spending, there is a budget surplus. In fiscal year 2022, the budget deficit was $1.376 trillion.

FEDERAL DEBT. Federal debt is composed of public debt issued by the Treasury (Treasuries) and a very small amount of agency debt issued by other federal agencies.[14] At the end of fiscal year 2022, public debt was $30.929 trillion (99.92 percent of federal debt), and agency debt was $19 billion (0.08 percent of federal debt).

Federal debt is divided by ownership into (1) federal debt held by the public, and (2) federal debt in governmental accounts. At the end of fiscal year 2022, federal debt held by the public was $24.319 trillion (both public and agency debt) and federal debt in governmental accounts was $6.630 trillion.[15] See Table 1-6 for a detailed composition of public debt at the end of fiscal year 2022.

- Federal debt held by the public includes all debt that the federal government has borrowed from other persons.[16] At the end of fiscal year 2022, the public held $23.674 trillion of marketable Treasuries,[17] $626 billion of nonmarketable Treasuries,[18] and $19 billion of agency debt. Federal debt held by the public is mainly the cumulative sum of all past federal budget surpluses and deficits. Since 2008, a rapid increase in federal direct loans has also boosted federal debt held by the public.[19] While budgetary rules add only subsidy costs to federal outlays, the Treasury must borrow to fund direct loans from financing accounts.[20] Federal debt held by the public is economically significant since it represents the total financial resources borrowed by the federal government that are not available to other persons for other productive uses. See Table 1-7 for the ownership of public debt held by the public.

- In contrast, federal debt held in governmental accounts arises from an artificial accounting convention.[21] At the end of fiscal year 2022, governmental accounts held nonmarketable Treasuries of $6.609 trillion and $21 billion of marketable Treasuries. Since the federal government is both the creditor and the debtor, the federal government could increase, decrease, or eliminate federal debt held in governmental accounts without any economic effects. Moreover, interest paid by the Treasury on federal debt in governmental accounts and interest received by the Treasury on federal debt in governmental accounts sums to zero. Therefore, net interest outlays include only interest payments on federal debt held by the public.

Budget process

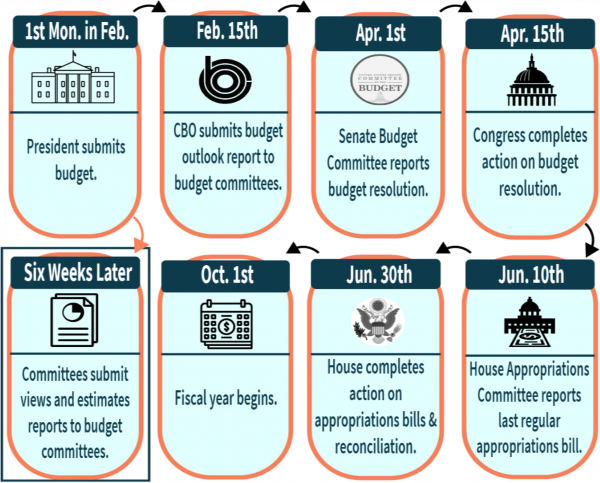

Executive budget process. Approximately 18 months before the beginning of a fiscal year, the OMB issues Circular A-10 to provide guidance on preparation of budget estimates by federal departments and agencies. Departmental secretaries and agency heads submit their budget estimates to OMB for review. Disputes are resolved by the OMB Director or ultimately the President by nine months before the beginning of a fiscal year. The OMB then prepares the Budget of the United States containing an analysis and justification for the President’s proposals. By law, the President is supposed to submit the Budget to Congress by the first Monday in February.[22]

Congressional budget process. Both the House of Representatives and the Senate have Budget Committees. The CBO prepares a 10-year Budget and Economic Outlook for submission to both budget committees by February 15. Within six weeks of the President’s submission of the Budget, the authorizing and tax-writing committees in each chamber submit their views on the Budget to their respective budget committee.

After a review of the President’s submission and the reactions of other committees, the budget committee in each chamber is supposed to develop a concurrent budget resolution. While the law does not provide a specific date for the House Budget Committee to report its budget resolution, the Senate Budget Committee is supposed to report a budget resolution by April 1. A concurrent budget resolution must meet the following requirements:

- Set targets for overall federal outlays, federal receipts, and federal budget balance over the next 10 fiscal years.

- Set separate outlay levels for each of the 12 annual appropriations bills that provide budget authority for all discretionary programs.

- Provide reconciliation instructions to (a) the authorizing committees to bring mandatory outlays within budget resolution targets and (b) tax-writing committees to bring tax receipts in line with budget resolution targets.

Once both chambers approve a concurrent budget resolution, any differences must be resolved through a conference committee and then be approved by both the House and Senate. This process is supposed to be completed by April 15.

There are two important things to know about concurrent budget resolutions. First, since the budget resolution is concurrent rather than joint, it is not submitted to the President and does not become law. It is merely a congressional rule. Second, there is no requirement for a budget resolution to control federal spending, reduce federal deficits, or achieve a federal budget balance. Indeed, a budget resolution can be used to increase federal spending and federal deficits.

If a budget resolution is approved, the reconciliation process begins. The authorizing and tax-writing committees in both the House and the Senate must develop specific changes in existing laws to meet their targets established in the budget resolution. In each house, the budget committee incorporates the specific changes from the other committees into a single reconciliation bill.

The Senate places additional limitations on the contents of a reconciliation bill.[23] A reconciliation bill that meets these requirements is not subject to filibuster, so only 51 votes rather than 60 votes are necessary to change entitlement and tax laws. For this reason, almost all significant changes affecting entitlements and taxes in the last three decades have been made through reconciliation.

Congress is supposed to complete action on reconciliation bills by June 15. Like any other law, a reconciliation bill must be approved by both the House and Senate in identical form and then sent to the President for signature or veto.

The House Appropriations Committee is supposed to report the 12 annual appropriations bills between May 15 and June 10. And the House is supposed to approve all 12 annual appropriations bills by June 30.

Unfortunately, Congress does not pass a concurrent budget resolution for every fiscal year. And Congress almost never adheres to the time deadlines in the budget law.

When Congress fails to adopt a concurrent budget resolution, each house passes simple “deeming resolutions” to set outlay targets for the 12 annual appropriations bills, or both the House and Senate attach a “deeming resolution” to another bill that became law.

When one or more annual appropriations bills have not been enacted by October 1, Congress passes a continuing resolution that maintains budget authority at its present level for a limited number of days until the enactment of the missing annual appropriations bills or an omnibus appropriations bill.

If Congress fails to pass a continuing resolution, or if the President vetoes it, the provisions of Antideficiency Act come into effect. Affected departments and agencies must cease operations except as otherwise provided by law until appropriations are enacted.

Federal debt limit. In addition to making decisions on how much to tax and spend, Congress periodically authorizes the Treasury to incur more federal debt by increasing the debt ceiling.[24] Unfortunately, the federal debt limit is based on total public debt, which (1) includes public debt held by the public and public debt in governmental accounts, and (2) excludes federal agency debt rather than federal debt held by the public. This definition is not economically correct because (1) federal agency debt is excluded, and (2) public debt held in governmental accounts is included. Federal debt held by the public would be the economically correct to base a debt limit. This definitional error produced the strange spectacle of Congress being forced to raise the federal debt ceiling by $450 billion in August 1997 when the federal budget was in surplus and public debt held by the public was falling. Moreover, this error misinforms the American public by overstating the federal debt burden currently borne by taxpayers.

Budget data

| TABLE 1-1 TOTAL FEDERAL OUTLAYS IN FISCAL YEAR 2022 PER OMB | |||

| Category | Billions of $ | Percent of Total Outlays | Percent of GDP |

| DISCRETIONARY OUTLAYS | $1,664.4 | 26.5% | 6.7% |

| MANDATORY OUTLAYS | $4,368.0 | 69.6% | 17.5% |

| NET INTEREST | $475.9 | 7.6% | 1.9% |

| UNDISTRIBUTED OFFSETTING RECEIPTS | -$235.0 | -3.7% | -0.9% |

| TOTAL FEDERAL OUTLAYS | $6,273.3 | 100.0% | 25.1% |

| TABLE 1-2 DISCRETIONARY OUTLAYS IN FISCAL YEAR 2022 PER OMB | ||||

| Category and Program | Billions of $ | Billions of $ | Percent of Total Outlays | Percent of GDP |

| Health | $141.5 | 2.3% | 0.6% | |

| Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services: | ||||

| Education | $108.0 | 1.7% | 0.4% | |

| Training, Employment, and Social Services | $26.2 | 0.4% | 0.1% | |

| Total Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services | $134.2 | 2.1% | 0.5% | |

| Veterans Benefits and Services (primarily healthcare) | $113.2 | 1.8% | 0.5% | |

| Transportation: | ||||

| Ground Transportation | $74.3 | 1.2% | 0.3% | |

| Air Transportation | $27.3 | 0.4% | 0.1% | |

| Water and Other Transportation | $10.6 | 0.2% | 0.0% | |

| Total Transportation | $112.2 | 1.8% | 0.4% | |

| Income Security: | ||||

| Housing Assistance | $57.9 | 0.9% | 0.2% | |

| Other | $35.0 | 0.6% | 0.1% | |

| Total Income Security | $92.9 | 1.5% | 0.4% | |

| Administration Of Justice | $67.6 | 1.1% | 0.3% | |

| Community And Regional Development | $45.5 | 0.7% | 0.2% | |

| Natural Resources and Environment | $43.8 | 0.7% | 0.2% | |

| General Science, Space, and Technology: | ||||

| General Science and Basic Research | $15.0 | 0.2% | 0.1% | |

| Space and other technology | $22.2 | 0.4% | 0.1% | |

| Total General Science, Space, and Technology | $37.2 | 0.6% | 0.1% | |

| General Government | $19.1 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| Agriculture | $16.2 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| Medicare | $7.9 | 0.1% | 0.0% | |

| Energy | $6.9 | 0.1% | 0.0% | |

| Social Security | $6.2 | 0.1% | 0.0% | |

| Commerce and Housing Credit | -$2.8 | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| DOMESTIC DISCRETIONARY OUTLAYS | $841.6 | 13.4% | 3.4% | |

| NATIONAL DEFENSE OUTLAYS | $715.7 | 11.4% | 2.9% | |

| INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS OUTLAYS | $70.6 | 1.1% | 0.3% | |

| DISCRETIONARY OUTLAYS | $1,628.0 | 26.0% | 6.5% |

| TABLE 1-3 MANDATORY OUTLAYS IN FISCAL YEAR 2022 PER OMB | ||||

| Category and Program | Billions of $ | Billions of $ | Percent of Total Outlays | Percent of GDP |

| Social Security | $1,212.5 | 19.3% | 4.8% | |

| Health: | ||||

| Medicaid | $591.9 | 9.4% | 2.4% | |

| Refundable Premium Tax Credit and Cost Sharing Reductions | $79.5 | 1.3% | 0.3% | |

| Children’s Health Insurance | $16.7 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| Indian Health Service | $0.9 | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Other | $83.6 | 1.3% | 0.3% | |

| Total health | $772.6 | 12.3% | 3.1% | |

| Medicare | $747.2 | 11.9% | 3.0% | |

| Income security: | ||||

| Food and Nutrition Assistance (includes SNAP) | $187.3 | 3.0% | 0.7% | |

| Refundable Child Tax Credit and Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit | $138.9 | 2.2% | 0.6% | |

| Refundable Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) | $64.3 | 1.0% | 0.3% | |

| Supplemental Security Income (SSI) | $58.8 | 0.9% | 0.2% | |

| Coronavirus Payments and Tax Credits | $42.6 | 0.7% | 0.2% | |

| Family and Other Support Assistance | $37.6 | 0.6% | 0.2% | |

| Unemployment Compensation | $33.1 | 0.5% | 0.1% | |

| Housing Assistance | $21.2 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| General Retirement and Disability (neither Social Security nor Federal Employees) | $11.8 | 0.2% | 0.0% | |

| Payments to States for Foster Care/Adoption Assistance | $9.2 | 0.1% | 0.0% | |

| Total Income Security | $604.6 | 9.6% | 2.4% | |

| Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services[25] | $543.2 | 8.7% | 2.2% | |

| Federal Employee Retirement and Disability | $168.6 | 2.7% | 0.7% | |

| Veterans Benefits and Services: | ||||

| Income Security for Veterans | $139.9 | 2.2% | 0.6% | |

| Other | $21.3 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| Total Veterans Benefits and Services | $161.2 | 2.6% | 0.6% | |

| Other Mandatory Programs: | ||||

| General Government | $114.1 | 1.8% | 0.5% | |

| Community and Regional Development | $24.5 | 0.4% | 0.1% | |

| All Other | $20.4 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| Agriculture | $16.8 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| National Defense | $13.7 | 0.2% | 0.1% | |

| Universal Service Fund | $7.8 | 0.1% | 0.0% | |

| International Affairs | $1.1 | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Deposit Insurance | -$11.6 | -0.2% | 0.0% | |

| Other Commerce and Housing Credit | -$12.6 | -0.2% | -0.1% | |

| Energy | -$16.0 | -0.3% | -0.1% | |

| Total other mandatory programs | $158.2 | 2.5% | 0.6% | |

| TOTAL MANDATORY OUTLAYS | $4,199.4 | 66.9% | 16.8% |

| TABLE 1-4 TOTAL FEDERAL RECEIPTS IN FISCAL YEAR 2022 PER OMB | |||

| Source | Billions of $ | Percent of Total Receipts | Percent of GDP |

| Individual Income Taxes | $2,632.1 | 53.7% | 10.5% |

| Social Insurance (Payroll) Taxes | $1,483.5 | 30.3% | 5.9% |

| Corporate Income Taxes | $424.9 | 8.7% | 1.7% |

| Federal Reserve Excess Profits | $106.7 | 2.2% | 0.4% |

| Customs Duties and Fees | $99.9 | 2.0% | 0.4% |

| Excise Taxes | $87.7 | 1.8% | 0.4% |

| Estate and Gift Taxes | $32.6 | 0.7% | 0.1% |

| All Other | $30.0 | 0.6% | 0.1% |

| TOTAL FEDERAL RECEIPTS | $4,897.4 | 100.0% | 19.6% |

| TABLE 1-5 FEDERAL DIRECT LOANS AND FEDERAL LOAN GUARANTIES OUTSTANDING AT THE END OF FISCAL YEAR 2022 PER OMB (in Billions of $) | |

| Federal Direct Loans: | |

| Federal Student Loans | $1,380 |

| Disaster Assistance | $382 |

| Farm Service Agency, Rural Development, Rural Housing[26] | $64 |

| Treasury Economic Stabilization Program | $20 |

| Rural Utilities Service and Rural Telephone Bank[27] | $56 |

| Education Temporary Student Loan Purchase Authority | $43 |

| Housing and Urban Development | $55 |

| Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Loans | $14 |

| Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing, Title 17 Loans | $16 |

| Export-Import Bank | $10 |

| International Assistance | $2 |

| Other direct loan programs | $30 |

| TOTAL FEDERAL DIRECT LOANS | $2,071 |

| Federal Guaranteed Loans: | |

| FHA Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund[28] | $1,276 |

| Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Mortgages | $941 |

| Small Business Administration (SBA) Business Loan Guarantees | $188 |

| FHA General and Special Risk Insurance Fund[29] | $187 |

| Farm Service Agency, Rural Development, Rural Housing[30] | $147 |

| Federal Student Loan Guarantees | $96 |

| Export-Import Bank | $14 |

| International Assistance | $9 |

| Other guaranteed loan programs | $40 |

| TOTAL FEDERAL GUARANTEED LOANS | $2,898 |

| TOTAL FEDERAL CREDIT | $4,969 |

| TABLE 1-6 COMPOSITION OF THE PUBLIC DEBT AT THE END OF FISCAL YEAR 2022 PER TREASURY (in Millions of $) | |||

| Debt Held by the Public | Government Accounts | Total | |

| Marketable | |||

| Bills | $3,643,675 | $945 | $3,644,620 |

| Notes | $13,696,488 | $7,308 | $13,703,795 |

| Bonds | $3,867,672 | $6,680 | $3,874,352 |

| Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities | $1,839,843 | $689 | $1,840,532 |

| Floating Rate Notes | $625,897 | $81 | $625,977 |

| Federal Financing Bank | $0 | $4,847 | $4,847 |

| Total Marketable | $23,673,574 | $20,550 | $23,694,124 |

| Nonmarketable | |||

| Domestic Series | $25,894 | $0 | $25,894 |

| Foreign Series | $264 | $0 | $264 |

| State & Local Government Series[31] | $109,236 | $0 | $109,236 |

| United States Savings Securities | $166,292 | $0 | $166,292 |

| Government Account Series[32] | $320,634 | $6,609,169 | $6,929,803 |

| Other | $3,298 | $0 | $3,298 |

| Total Nonmarketable | $625,618 | $6,609,169 | $7,234,788 |

| TOTAL PUBLIC DEBT SECURITIES | $24,299,193 | $6,629,719 | $30,928,912 |

| TOTAL PUBLIC DEBT SECURITIES AS A PERCENT OF GDP | 97.2% | 26.5% | 123.7% |

| TABLE 1-7 OWNERSHIP OF PUBLIC DEBT HELD BY THE PUBLIC AT THE END OF FISCAL YEAR 2022 PER TREASURY | |||

| Owners | Billions of $ | Percent of Public Debt Held by the Public | Percent of GDP |

| Federal Reserve | $5,635.0 | 23.2% | 22.5% |

| Depository Institutions | $1,740.1 | 7.2% | 7.0% |

| US Savings Bonds | $166.2 | 0.7% | 0.7% |

| Private Pension Funds | $749.6 | 3.1% | 3.0% |

| State and Local Government Pension Funds | $366.3 | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Insurance Companies | $371.6 | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Mutual Funds | $2,605.8 | 10.7% | 10.4% |

| State and Local Governments | $1,537.4 | 6.3% | 6.1% |

| Foreign and International | $7,302.6 | 30.1% | 29.2% |

| Domestic Individuals and Other Investors | $3,824.6 | 15.7% | 15.3% |

| PUBLIC DEBT HELD BY THE PUBLIC | $24,299.2 | 100.0% | 97.2% |

Note: Data on the ownership of agency debt are not available.

Appendix I: The Federal Budget and the Constitution

Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution authorizes Congress to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence [sic] and general Welfare of the United States” and “borrow Money on the credit of the United States.” The 16th Amendment to the Constitution authorizes Congress to “lay and collect taxes on incomes.”[33] The Constitution as originally written places five requirements on fiscal policy:

- Congress may not levy tariffs on exports.

- Congress may not make appropriations for the army for more than two years.

- The Treasury may make outlays only pursuant to an appropriations law.

- A regular statement of receipts and expenditures must be published.

The 10th Amendment limits the powers assigned to the federal government to those enumerated in Article I, Section 8 or elsewhere in the Constitution. However, the re-interpretation the interstate commerce clause in the 1930s so broadened federal powers that specified powers no longer impose significant limits on federal spending. Finally, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution adds that U.S. government debt incurred pursuant to law is valid and may not be questioned in any court.

Otherwise, the Constitution does not limit federal spending, taxing, and borrowing. Congress exercises its fiscal powers through the constitutionally prescribed enactment of laws. Thus, a sitting Congress cannot limit the fiscal decisions of future Congress. Binding limitations can be imposed only by amending the Constitution.

In this regard, the U.S. Constitution differs from many constitutions in U.S. states and other democratic countries. Their constitutions impose a more detailed budget process and limits on spending, taxing, and borrowing. These include:

- Supermajority votes in legislative bodies to increase spending, raise taxes, or incur debt

- Referendum requirements to increase spending, raise taxes, or incur debt

- Line-item, item-reduction, or amendatory veto by the executive

- Spending limits tied to inflation plus population growth

- Spending limits tied to income growth or the size of the economy

Appendix II: History of the Budget Process

Prior to 1921, there was neither a federal budget nor a federal budget process. Secretaries sought appropriations for their departments directly from Congress as needed. The President had little opportunity to review and prioritize departmental spending requests, and Congress lacked the ability to audit departments to determine how appropriations were actually spent. The explosive growth of federal spending during World War I made this nonsystematic approach impractical and wasteful.

On April 11, 1921, before a joint session of Congress, President Warren Harding advocated the creation of a unified federal budget and a federal budget process to control federal spending. On June 10, 1921, President Harding signed the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, which established a federal budget process. This act established the Bureau of the Budget in the Treasury to review the appropriations requests from the departments and compile a federal budget, which contains all of the President’s proposed appropriations and tax changes for the next fiscal year, for submission to Congress. In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt moved the Bureau of Budget from the Treasury to the Executive Office of the President (EOP) by executive order. In 1970, President Richard Nixon reorganized the bureau into the Office of Management and Budget within the EOP. The act also established the General Accounting Office (GAO) to audit and evaluate the effectiveness of spending on behalf of Congress. In 2004, the GAO Human Capital Reform Act changed the name of the GAO to the Government Accountability Office.

Prior to 1974, Presidents could choose to not spend funds that Congress had appropriated in a process known as impoundment. Because impoundment affected the spending power that the Constitution granted to Congress, Presidents before Richard Nixon consulted Congress and used impoundment sparingly to cancel unnecessary appropriations when program costs were below expectations. In contrast, Nixon impounded large sums without consulting Congress to block spending on programs to which Nixon objected, but Congress approved. By bipartisan, veto-proof majorities, Congress passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974. Admitting defeat, Nixon signed this act on July 12, 1974. The act established the Congressional Budget Office and created the congressional budget process.

Since 1985, Congress has enacted several laws that have modified existing budgetary procedures and added statutory controls to limit future spending increases or require future deficit reductions. The Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 established a statutory requirement for the gradual reduction and elimination of the federal budget deficit over six fiscal years. The act specified annual budget deficit limits and mandated an enforcement process known as sequestration through which a President must issue an order limiting outlays if Congress failed to achieve the annual budget deficit target. The Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Reaffirmation Act of 1987 modified these budget deficit targets and extended their timeline. A weakness of the sequestration process was that Congress exempted many programs from any sequester and severely limited any sequester in other programs. Thus, a small sequestration order caused large spending reductions in the remaining programs.

The Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 focused on discouraging future legislation that could increase budget deficits. This act established (1) a statutory cap on the growth of discretionary spending and (2) a PAYGO procedure to prevent any increase in the federal budget deficit from expanding mandatory spending or reducing taxes. PAYGO required an offsetting reduction in mandatory spending or an increase in taxes to pay for an increase in mandatory spending or a reduction in taxes. The statutory discretionary cap and PAYGO were to be in force for five fiscal years but were extended twice to fiscal year 2002.

In 2010, the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010 reinstated PAYGO. In 2011, the Budget Control Act reinstated discretionary spending caps divided into separate defense and nondefense caps for 10 fiscal years. These caps and procedures were modified over time and expired at the end of fiscal year 2021.

Collectively, these laws had modest positive effects on budgetary outcomes. In the first year or two, spending growth lessened, and budget deficits generally improved. Since one Congress cannot bind future Congresses, however, statutory procedures and spending caps were loosened, repealed, or allowed to expire over time when they became too politically difficult to implement.

Appendix III: Major Entitlement Programs

- Social Security

- Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI)

- Disability Insurance (DI)

- Major Medical

- Medicare

- Medicaid

- Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- Health insurance subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (ACA)

- Income security entitlements

- Refundable portion of Earned Income and Child Tax Credits

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) formerly known as Food Stamps

- Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

- Unemployment Insurance (UI)

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

- Child Support Enforcement

- Childcare programs

- Child nutrition programs

- Federal civilian and military retirement

- Veterans compensation, pension, life insurance, and education benefits[34]

- Other entitlements

- Agricultural subsidy programs

- Department of Defense Medicare-Eligible Retiree Health Care (Tricare for Life)

Appendix IV: The 12 Annual Appropriations Laws

- Agriculture

- Commerce, Justice, Science

- Defense

- Energy and Water

- Financial Services and General Government

- Homeland Security

- Interior and Environment

- Labor, HHS, Education

- Legislative Branch

- Military Construction and VA

- State, Foreign Operations

- Transportation, HUD

__________________________________

* Robert P. O’Quinn is the former Chief Economist at both U.S. Department of Labor and U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means and former Executive Director at the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee.

[1] National defense includes most operations of the Department of Defense and defense-related atomic energy activities at the Department of Energy.

[2] International affairs include most operations of the Department of State, foreign military assistance, and foreign humanitarian assistance.

[3] Appropriations legislation include regular appropriations laws, supplemental appropriations laws, and continuing resolutions.

[4] Incurring financial obligations involves employing federal workers and contracting to purchase goods and services.

[5] Budget authority and outlays will not be equal in any fiscal year for two reasons. First, budget authority for physical investments such as buildings or roads in one fiscal year may create outlays in several fiscal years. Second, timing differences particularly near the end of a fiscal year may cause budget authority in one fiscal year to create outlays in another fiscal year.

[6] From the establishment of the federal government in 1789 to 1842, the fiscal year was the same as the calendar year. In 1842, President John Tyler signed a law, which accelerated the start of fiscal year 1843 by two quarters from January 1, 1843, to July 1, 1842. Thus, fiscal year 1842 was only six months. A provision of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 delayed the start of fiscal year 1977 from July 1, 1976, to October 1, 1976, with the quarter beginning on July 1, 1976, becoming a Transition Quarter. Since then, the fiscal year begins on October 1 of the prior calendar year and end on September 30 of the calendar year.

[7] Federal entitlement programs provide benefits to or on behalf of all qualified persons based on a formula set in an authorization law. Persons may be individuals, firms, non-profit organizations, state governments, or local governments.

[8] Funding for a few entitlement programs is appropriated annually. These entitlements include Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), Veterans’ disability compensation and pensions, and Medicaid. Outlays for these entitlements are mandatory because (1) their authorization acts require the federal government to provide benefits to eligible people, or (2) other laws require such entitlements be treated as mandatory.

[9] The Treasury receives interest payments from federal financing programs and dividend and interest payments from assets in the National Railroad Retirement Investment Trust.

[10] Offsetting collections and offsetting receipts are funds that government agencies receive from the public and from other federal agencies (in what are known as governmental transactions) for businesslike or market-oriented activities. Offsetting collections are used for specific spending programs and are credited to the accounts that record outlays for such programs. Examples of offsetting collections are the sale of postage stamps, the sale of electricity from the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Bonneville Power Administration, federal employee and retiree contributions for health insurance, Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation premiums, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation premiums, sales at military commissaries, Federal Crop Insurance premiums, and patent and trademark fees, and National Flood Insurance premiums. Offsetting receipts are recorded in stand-alone accounts that are separate from spending accounts. Such receipts are not automatically available for an agency to spend but are generally considered to offset mandatory spending. Offsetting receipts include Medicare parts B and D premiums, spectrum sales, leases of the Outer Continental Shelf, and immigration fees.

[11] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the OMB use different accounting conventions regarding the application of offsetting collections and receipts against specific discretionary and mandatory outlays. OMB is more aggressive than CBO, so CBO records larger unapplied offsetting collections and receipts than OMB. In fiscal year 2022, for example, CBO recorded undistributed offsetting collections and receipts of minus $504.7 billion, while OMB recorded undistributed offsetting collections and receipts of minus $235.0 billion. While not affecting total federal outlays, different accounting conventions affect the outlays recorded for specific programs with CBO higher than OMB. In some cases, the difference is very significant. In fiscal year 2022, for example, CBO reported Medicare outlays of $974.8 billion, while OMB reported Medicare outlays of $747.2 billion, a difference of $227.6 billion. When examining specific programs, one must be careful to use consistent gross or net data through time.

[12] At the end of fiscal year 2022, outstanding Federal Student Loans and Disaster Assistance Loans were $1.380 trillion and $382 billion, respectively. Together they accounted for 85.0 percent of all federal direct loans outstanding. Similarly, FHA and VA guarantied mortgage loans outstanding were $1.276 trillion and $941billion, respectively. They accounted for 76.5 percent of federal loan guarantees outstanding.

[13] Foreign governments, especially foreign central banks, are major buyers of U.S. government bonds.

[14] For federal budgetary purposes, only the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) may issue agency debt. TVA issued over 99 percent of agency debt outstanding. The remainder is divided between the Architect of the Capitol and the FHA. Note the definition of agency debt for federal budgetary purposes is different than the definition of agency debt commonly used in financial markets. Debt issued by four government-sponsored enterprises—Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Federal Home Loan Banks, and Farm Credit System—is not defined as agency debt for federal budgetary purposes but is defined as agency debt for financial market purposes. These four government-sponsored enterprises have issued $8.7 trillion in agency debt at end of fiscal year 2022.

[15] Public debt, federal debt held by the public, and public debt held by the public are different concepts that are frequently confused.

[16] Persons include individuals, non-financial businesses, financial institutions, and non-profit organizations both domestic and foreign; the Federal Reverse and foreign central banks; and foreign governments.

[17] Marketable Treasuries include bills, notes, bonds, Treasury inflation-protected securities, and floating rate notes.

[18] Nonmarketable Treasuries include Savings Bonds, State and Local Government Series, and certain other series.

[19] At the end of fiscal year 2022, the Treasury owned $1.6 trillion of debt securities issued by other federal agencies to finance direct loans from various agencies and physical assets of the Bonneville Power Administration. The Treasury borrowed an equal amount from the public to purchase these debt securities.

[20] The change in federal debt held by the public during a fiscal year will not necessarily equal the federal budget deficit or surplus because of several factors. These factors include changes in the Treasury’s cash balances due to the timing of borrowing and debt repayment, seigniorage profits from coinage, net cash flows from credit financing accounts, changes in cash balances on non-budgetary accounts held by Treasury for others (e.g., state income tax withholding for federal employees), and transactions with the International Monetary Fund.

[21] The excess of dedicated receipts over previous outlays for specific mandatory programs are recorded as nonmarketable Treasury debt in “trust funds” that comprise governmental accounts.

[22] For a year in which a new President is inaugurated, the due date for the Budget is the first Monday in March.

[23] Under the Byrd rule, a provision is ineligible for inclusion in a reconciliation bill if:

- It does not change outlays or receipts.

- It produces an outlay increase or a receipt decrease when the instructed committee is not in compliance with its instructions.

- It is outside the jurisdiction of the committee that submitted the provision.

- It produces a change in outlays or receipts that is merely incidental to its nonbudgetary provisions.

- It increases budget deficits beyond the fiscal years covered in the budget resolution.

- It changes Social Security.

[24] From 1789 to 1917, Congress managed federal debt by authorizing the Treasury to issue specific federal debt securities rather than placing an aggregate limit on federal debt. The Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917 began the move from disaggregated limits on specific federal debt issues to a single aggregate limit on federal debt. On July 20, 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt signed a law establishing a single aggregate limit on federal debt. This change allowed the Treasury to manage federal debt securities outstanding more efficiently.

[25] Included is a $400 billion loss in the present value of expected interest and principal payments due to President Biden’s initiative to forgive student loan debts, which is currently before the Supreme Court.

[26] Farm Service Agency of the Department of Agriculture provides (1) mortgage loans for single-family residences in rural areas; (2) mortgage loans for multi-family rental housing for low-income, elderly, and disabled individuals and families as well as domestic farm laborers in rural areas; and (3) mortgage loans to develop or improve essential public services and facilities in rural areas.

[27] The Rural Utilities Services of the Department of Agriculture provide loans for (1) drinking water, sanitary sewer, solid waste, and storm drainage facilities in rural areas; (2) electric distribution, transmission, and generation facilities in rural areas; and (3) telecommunications infrastructure in rural areas.

[28] FHA Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund guarantees mortgage loans for single-family residences.

[29] FHA General and Special Risk Insurance Fund guarantees mortgage loans for multi-family rental housing, nursing homes, and hospitals.

[30] Farm Service Agency, Rural Development, Rural Housing guarantees (1) mortgage loans for single-family residences in rural areas; (2) mortgage loans for multi-family rental housing for low-income, elderly, and disabled individuals and families as well as domestic farm laborers in rural areas; and (3) mortgage loans to develop or improve essential public services and facilities in rural areas.

[31] The Treasury issues non-marketable State and Local Government Series to state and local governments that have excess cash from issuance of tax-exempt bonds. The federal tax code generally forbids investment of such cash in securities that offer a higher yield than the original bond, but SLGS securities are exempt from this restriction.

[32] The Treasuries issues non-marketable Government Series (held by the public) for investments by federal employees and retirees in the G Fund of the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP).

[33] The Constitution original required that Congress appropriation all direct taxes among the states based on the most recent census. The 16th Amendment removed this requirement.

[34] Veterans’ health care benefits are considered discretionary outlays.

———

Image credit: Bjoertvedt | CC BY-SA 3.