Narratives matter in public policy, often in an unfortunate manner.

- People used to believe (and some still do) that the Great Depression was caused by capitalism and that President Roosevelt’s interventions rescued the economy. Those people are wrong.

- People used to believe (and some still do) that the 2008 financial crisis was caused by Wall Street “greed” and that laws such as Dodd-Frank will protect us in the future. Those people are wrong.

Another narrative is that the industrial revolution was a horrible period in American economic history that produced immense wealth for so-called robber barons while leading to suffering and deprivation for everyone else.

Today, we will look at why that is nonsense.

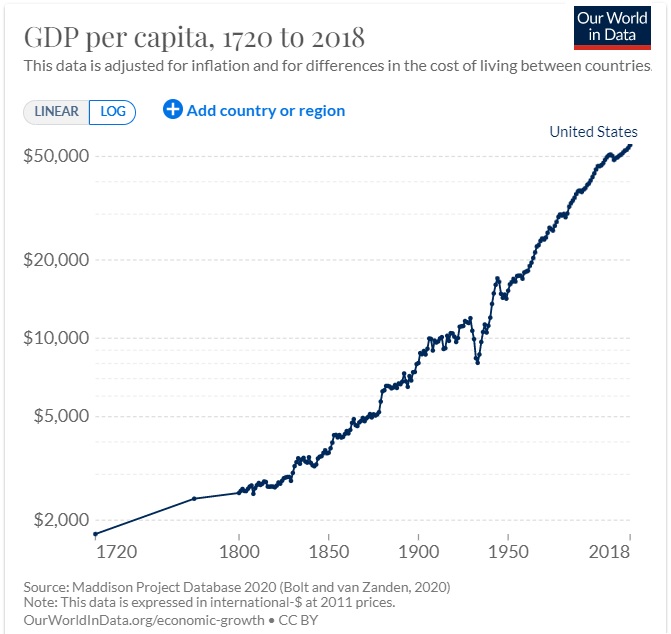

We’ll start with this chart from Oxford University’s Our World in Data. As you can see, per-capita GDP increased sharply in the latter part of the 19th century (the period most associated with “robber barons” and the industrial revolution.

I’m motivated to address this topic today because of an excellent column I just read in the Wall Street Journal. The authors, former Senator Phil Gramm and renowned author Amity Shlaes, start by presenting the myth.

The rise of progressivism before the turn of the 20th century was fueled by the perception that “robber barons” of industry and finance had earned their fortunes from their monopoly power that allowed them to exploit the poor and middle class. …French economist Thomas Piketty concluded that the middle class “suffered a setback during the Gilded Age.” Likewise, in the teacher’s guide to his bestselling American history textbook, Howard Zinn writes that “ordinary people who lived through the Gilded Age…experienced tremendous hardships and losses… While they got poorer, the rich were getting richer.” …the Gilded Age suffered from monopolistic exploitation, as critics claim.

They then present the facts.

…the underlying economic claims are at variance with the facts. …Between 1870 and 1900, America’s inflation-adjusted gross national product expanded by an unprecedented 233%. Though the population nearly doubled, real per capita GNP surged by 90%. Real wages of nonfarm employees grew by 53%, and life’s staples, such as food, clothing and shelter, became more plentiful and much cheaper. Food prices plummeted by 63% and the cost of textiles, fuel and home furnishings fell by 70%, 65% and 70%, respectively. …In 1892 there were 4,050 millionaires, with less than 20% having inherited their wealth. The rest created it and in the process reduced poverty, expanded general societal prosperity… That mattered little to progressives, who were so obsessed by the 4,050 millionaires that they turned a blind eye to the 66 million Americans whose economic well-being improved faster than any people who had ever lived on earth. …On average, prices in the ostensibly monopolized industries fell three times as fast as the consumer price index. …progressivism is based on a myth and fueled by envy.

However, not all robber barons were admirable. As the title to this column suggests, only the ones competing in the market were good.

Those that got rich via government favoritism, by contrast, were bad.

Rachel Chiu made this point in her 2021 column for National Review.

…not all entrepreneurs during the Gilded Age were corrupt. Market entrepreneurs were successful because they offered superior products at low prices, while political entrepreneurs relied on the government to intercede on their behalf. For example, steamboat inventor Robert Fulton developed a successful commercial service because the New York legislature granted him a 30-year monopoly on the Hudson River. Cornelius Vanderbilt, on the other hand, built his steamboat empire without government-granted privileges. …abuses associated with the Gilded Age were enabled by an unhealthy relationship between government and capital that distorted the operation of free markets. “Political entrepreneurship” must be discouraged, but entrepreneurs (in the classic sense of that word) should not.

In a 2021 article for the Mises Institute, Antonis Giannakopoulos also recognized the difference between honest wealth and dishonest wealth.

According to popular “wisdom,” people like John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and others made profits due to immoral and unethical competition practices that granted a monopoly status to their companies. …we must first of all make a distinction between, as historian Burton Folsom says ‘”the market entrepreneur and the political one.” …The famous steamship entrepreneur Cornelius Vanderbilt had to compete with political entrepreneurs who received subsidies and special privileges from the government. …Enemies of the free market have infiltrated the minds of the public with a mix of oversimplified history and facts, and bad economics.

For more on this, I recommend videos by Burton Folsom, Milton Friedman, and Brian Domitrovic.

P.S. I can’t resist sharing some scholarly analysis of why antitrust laws were first enacted.

Senator John Sherman of Ohio was motivated to introduce an antitrust bill in late 1889 partly as a way of enacting revenge on his political rival, General and former Governor Russell Alger of Michigan, because Sherman believed that Alger personally had cost him the presidential nomination at the 1888 Republican national convention. …Sherman repeatedly brought up Alger’s relationship, which in reality was rather tenuous, with the well-known Diamond Match Company. The point of mentioning Alger was to hurt Alger’s future political career and his presidential aspirations in 1892. …this paper reinforces previous public choice literature arguing that the 1890 Sherman Act was not passed in the public interest, but instead advanced private interests.

In other words, antitrust laws were enacted for the benefit of politicians and their cronies, not for the benefit of consumers.

P.P.S. In a two-part interview with John Stossel, I gave my two cents about monopolies and robber barons.