Thanks in large part to the pro-growth agendas of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, but also giving credit to policymakers in nations like Ireland and Switzerland, businesses (and their workers, consumers, and shareholders) have benefited from four decades of tax competition.

How much have they benefited?

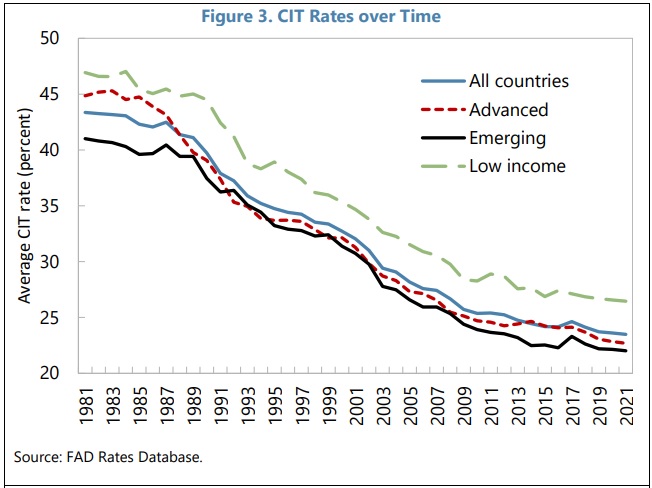

As shown by this chart, average corporate tax rates have dropped by about half since the early 1980s.

Not everybody is happy that corporate tax rates have declined.

Politicians in high-tax nations have always resented tax competition and they have been working through left-leaning international bureaucracies to push for various forms of tax harmonization.

Unfortunately, they have been partially successful.

Over the past 20 years, the human right of financial privacy has been substantially eroded so that uncompetitive governments can track – and tax – money that migrates to low-tax jurisdictions.

As a result, politicians recently have been raising personal income tax rates.

And they want to also raise corporate income tax rates, which is why many pro-tax politicians (including Joe Biden) are supporting a global tax cartel on business income.

The International Monetary Fund has a new report praising this effort. Authored by Ruud de Mooij, Alexander Klemm, and Christophe Waerzeggers, it celebrates the fact that politicians will be diverting more money from the productive sector of the economy

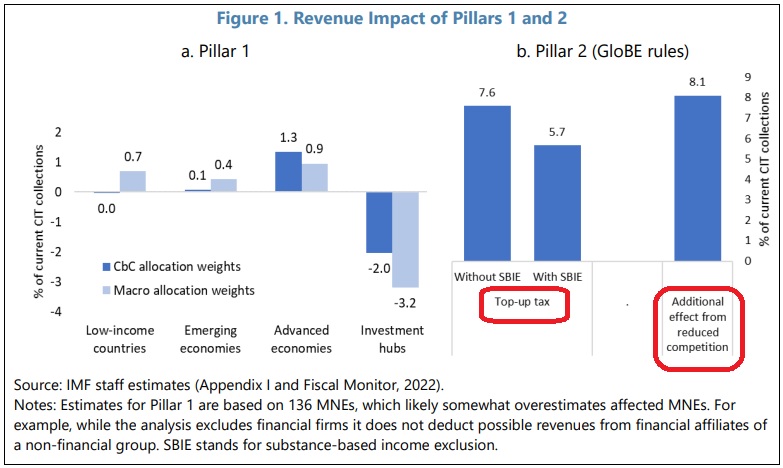

P1 is estimated to reallocate about 2 percent of total profits of MNEs, mainly from low-tax investment hubs to other countries, raising global Corporate Income Tax (CIT) revenue by $12 billion. …P2 would raise global CIT revenues by 5.7 percent, which is before any behavioral responses by firms (Figure 1b). According to staff simulations, 18.5 percent of global profit of MNEs is taxed below 15 percent ($1.47 trillion in 2019). On average, the current tax rate on these profits is 5 percent, so that profits exceeding the substance-based income exclusion would be subjected to a average top-up tax of 10 percent. …An additional positive revenue impact from P2 could come from reduced competition over corporate tax rates, which could boost global CIT revenues by an extra 8.1 percent. …a 1 percentage point increase in the world average CIT rate will, on average, induce a country to raise its own rate by 0.6 percentage points. By putting a floor of 15 percent, the simulations above suggest that 18.5 percent of MNE profit will indeed face a higher CIT burden, implying that countries will feel less pressure to keep their own tax rates low. Using simulations of the tax competition model, we find that the average CIT rate would rise from 22.2 to 24.3 percent due to the global minimum tax. The associated boost in global CIT revenues would be 8.1 percent, exceeding the direct effect on revenue.

By the way P1 is Pillar 1, which is the proposal to give powerful nations a bigger claim on the taxable income of big companies. By contrast, P2 is Pillar 2, which is the proposal for a mandatory minimum tax of at least 15 percent on corporate income.

In other words, a tax cartel.

As you can see from this next chart, most of the additional revenue is the result of the scheme for a 15 percent tax cartel.

I’ll close with two observations about this depressing data.

First, the IMF’s own research shows that reductions in corporate tax rates have not resulted in lower revenues. But I guess they now want to ignore the Laffer Curve since politicians want to grab more money.

Second, we should all be outraged that IMF bureaucrats (including the authors of the paper cited above) receive tax-free salaries while pushing for higher taxes on the rest of us.

———

Image credit: IMF | Public Domain.