What’s the best way of helping poor countries achieve faster growth so they can converge with rich nations?

Sensible people respond with a range of good answers.

- Removing trade barriers.

- Lowering corruption.

- Improved rule of law.

- Minimizing red tape.

- Reducing fiscal burdens.

- Sound monetary policy.

Unfortunately, the world has plenty of people who are not sensible (or who have a self-interested reason to make senseless arguments). And some of them have congregated at the International Monetary Fund.

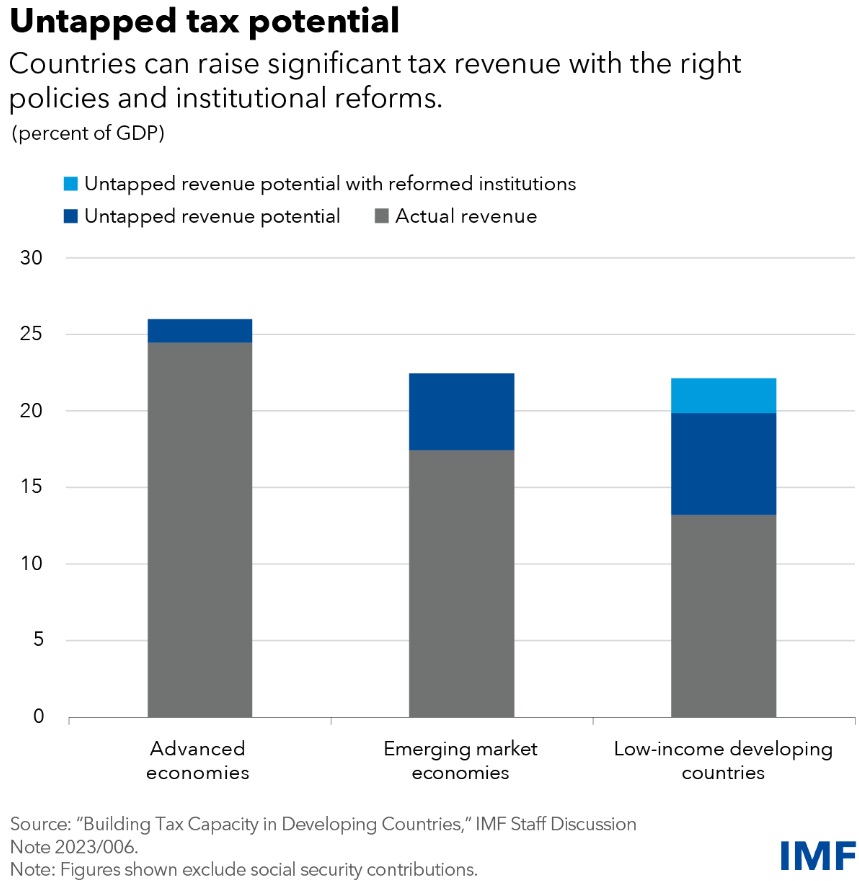

That bureaucracy recently published its recipe for economic development and – keeping with long-standing IMF tradition – endorsed massive tax increases for poor nations. Here’s their main recommendation.

You may be wondering why IMF bureaucrats want to make life more difficult for people in developing nations.

Here’s some of what was written by Vitor Gaspar, Mario Mansour, and Charles Vellutini.

Emerging markets and developing economies need $3 trillion annually through 2030 to finance their development goals … That amounts to about 7 percent of these countries’ combined 2022 gross domestic product and poses a formidable challenge… Our new research finds that many countries have the potential to increase their tax-to-GDP ratios—enabling them to provide critical government services—by as much as 9 percentage points… Countries have considerable room to collect more revenue based on their tax potential… We find that low-income countries could raise their tax-to-GDP ratio by as much as 6.7 percentage points on average. …The total revenue-raising potential, at 9 percentage points of GDP—a staggering two-thirds increase relative to their tax-to-GDP ratio in 2020… Similarly, emerging market economies can raise their tax-to-GDP ratio by 5 percentage points on average.

There are two things to address in the above excerpt.

First is it possible that developing nations, with sufficient “tax effort,” can increase their tax burdens by an average of 9 percentage points of GDP? Perhaps.

Second (and far more important), would that be a good idea? For people who care about empirical reality, definitely not.

Allow me to briefly elaborate on this second point. Bureaucrats at the IMF want readers to blindly accept the assertion that $3 trillion of additional tax revenue will help achieve development goals.

But notice that the IMF does not provide any supporting evidence. And neither do any of the other international bureaucracies making similar arguments.

Why don’t they offer any evidence? Why have not responded to my repeated requests to provide at least one example of a country that got rich by increasing fiscal burdens?

For the simple reason that every rich country in the world got rich when it had small government and low taxes.

In other words, the nations that achieved “development goals” took the opposite approach of what the IMF is recommending.

P.S. If the world truly is suffering from inadequate tax revenue, you would think that IMF bureaucrats would give up their special perk of tax-free salaries. But don’t hold your breath waiting for that to happen.

P.P.S. To give the IMF credit, the bureaucrats don’t discriminate. Yes, they push for bad fiscal policy in relatively poor parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, but they also argue for higher taxes and bigger government in relatively rich places, like Japan, Europe, and the United States.

———

Image credit: IMF | Public Domain.