Back in 2010, I shared a comparison of Obama and JFK on tax policy. For an update, here’s a comparison of Biden’s class-warfare agenda with JFK’s supply-side agenda.

I’m sharing this video for two reasons.

The first reason is that it shows that some Democrats in the past were very sensible about tax policy.

The second reason is that it gives me a good excuse to discuss what we can learn from tax policy in the 1960s, thus adding to our collection.

- Tax Lessons from the 1920s

- Tax Lessons from the 1930s

- Tax Lessons from the 1950s

- Tax Lessons from the 1980s

I’ll start with the caveat that tax policy does not necessarily overlap with 10-year periods. But we can learn by examining significant tax policy changes that occurred (or, in the case of the 1950s, did not occur) during various eras.

For the 1960s, the key change was the Revenue Act of 1964, generally known as the Kennedy tax cuts (proposed by President Kennedy in 1963 and then adopted in 1964 after his assassination).

Here’s what Kennedy proposed, as explained by the JFK library.

Declaring that the absence of recession is not tantamount to economic growth, the president proposed in 1963 to cut income taxes from a range of 20-91% to 14-65% He also proposed a cut in the corporate tax rate from 52% to 47%. …arguing that “a rising tide lifts all boats” and that strong economic growth would not continue without lower taxes.

And here’s what was enacted, as summarized by Wikipedia.

The act cut federal income taxes by approximately twenty percent across the board, and the top federal income tax rate fell from 91 percent to 70 percent. The act also reduced the corporate tax from 52 percent to 48 percent and created a minimum standard deduction.

The good news is that the Kennedy tax cuts were the right kind of tax cuts. Marginal tax rates were reduced on work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurship.

The bad news is that the top tax rate was still confiscatory, though 70 percent obviously was not as bad as 91 percent. And a 48 percent corporate rate was not much of an improvement compared to 52 percent.

That being said, moving in the right direction produced good outcomes.

People often talk about the booming economy in the 1960s. And there is some evidence to support that view since inflation-adjusted economic output grew rapidly as the tax cuts were implemented – by 6.5 percent in 1965 and 6.5 percent in 1966.

But I’m cautious about drawing sweeping conclusions from short-run data, especially since we know many other policies also have an impact on economic performance.

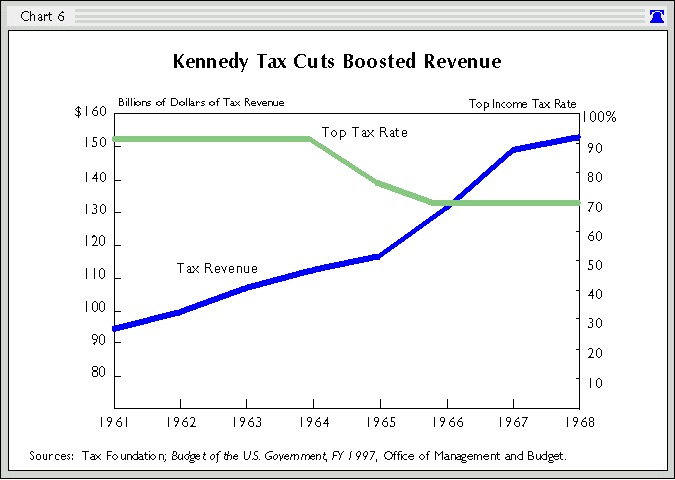

So let’s focus instead on some tax-related variables. Here’s a chart that I shared back in 2015, showing that upper-income taxpayers paid more when tax rates were reduced (the same thing happened in the 1980s).

That chart was taken from a report I wrote way back in 1996.

And here’s another chart from the same publication. This one shows that lower tax rates were associated with rising revenues. Especially as the changes were being implemented.

By the way, this does not mean that the tax cut was self-financing.

The core lesson of the Laffer Curve is not that tax cuts “pay for themselves.” That only happens in rare circumstances.

Instead, the lesson is that lower tax rates encourage more productive behavior, which means more taxable income. It then becomes an empirical question of how much of the revenue lost from lower rates is offset by the revenue gained from more taxable income.

And, in the 1960s, we know there was a big Laffer Curve response from upper-income taxpayers. Why? Because they have considerable control over the timing, level, and composition of this income.

Which brings us to the final lesson, which is that class-warfare tax policy was a bad idea in the 1960s and it is still a very bad idea today.