About 15 years ago, I narrated a three-part series on the Laffer Curve. Here’s Part II, which looks at real-world evidence.

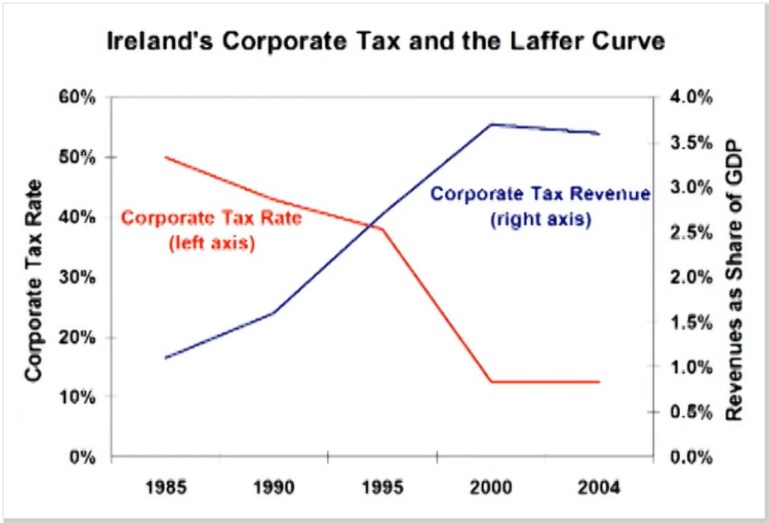

About halfway through the video (3:15-3:55), I discuss what happened when Ireland dramatically lowered its corporate tax rate.

The net result was an increase in tax revenue.

But not just by a small amount. I included a chart showing that corporate tax revenue as a share of GDP significantly increased in response to the lower rate.

And I made sure to point out that economic output also increased dramatically, meaning that the Irish government not only got a bigger slice of the pie, but also that the pie was much larger.

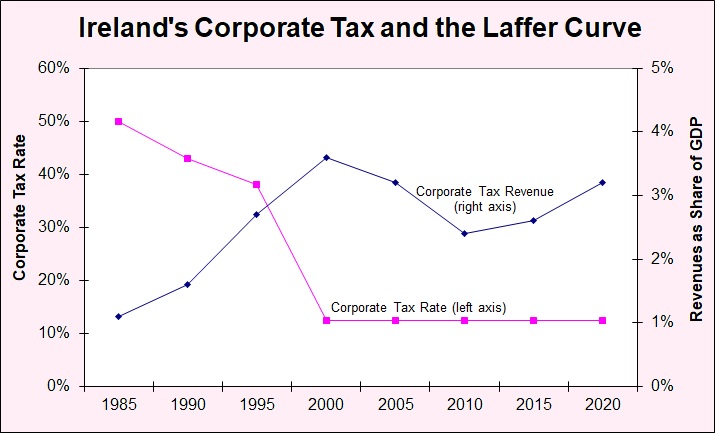

I’ve been asked a few times, however, whether that was a transitory phenomenon.

The answer is no. Using OECD data, I’ve updated the chart to also show what’s happened in the past 15 years. As you can see, corporate tax revenue has averaged close to 3 percent of economic output.

I realize that some folks on the left will be skeptical, even though I’m using data from the left-leaning OECD.

But perhaps they’ll believe the New York Times.

Ed O’Loughlin reports that Irish corporate tax revenues are so buoyant that the government in battling over how to allocate a budget surplus.

Ireland…is discovering that having too much money can…be a problem. Swollen by rising corporate tax revenue, mainly from American tech and pharmaceutical corporations, the government is expecting to have a record budget surplus of 10 billion euros ($10.9 billion) this year. Next year, the windfall is projected to be even larger, reaching €16 billion. For years, Ireland’s low corporate tax rate has lured multinational organizations to set up overseas subsidiaries here. Their tax payments have created a financial cushion for the government… Which leaves Irish lawmakers in a quandary. As the government prepares its annual budget statement in October, it must settle the tricky question of what to do with this pot of money. Chief among the options: save it for the future; pay off debts; invest in badly needed housing or some other infrastructure, like hospitals, schools and a subway system for Dublin; or give it away in tax cuts and support payments.

For what it’s worth, the obvious answer is lower tax rates on households (an area where Ireland scores very poorly).

Spending increases, by contrast, would be a very bad idea, especially since that approach has backfired in the past.

I’ll close with a final observation that Ireland is a success story, but GDP data create an excessively optimistic picture.

P.S. The NYT article also points out that big-ticket infrastructure projects suffer from massive cost overruns (sound familiar?).

…one obstacle to spending money on major projects, said Eoin Reeves, an economics professor at the University of Limerick, is that the Irish government has not been efficient at spending large sums of money on big investments. …Even by global standards, big infrastructure projects in Ireland tend to be completed late and far over budget. In 2015, a new 380-bed national children’s hospital in Dublin was projected to open by 2020, at a cost of €650 million. Its opening date has now been postponed until next year and at a cost of almost €2.2 billion — which reportedly could make it the most expensive hospital in the world, in terms of cost per bed. …plans for a line to its busy airport, with an estimated price tag in 2000 of €3.5 billion, have been repeatedly postponed or modified. The latest plan, if it ever gets underway, would take about 10 years to construct, at a cost of €7 billion to €12 billion.

P.P.S. The article also notes that the OECD’s global minimum tax scheme will hurt Ireland.

…the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development is leading an effort to create a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15 percent, which could flatten Ireland’s tax-rate advantage.

It is true that Ireland will become less competitive, but there are many other losers when governments conspire against taxpayers.

P.P.P.S. Ireland was a role model of spending restraint in the late 1980s.