I have written dozens of columns explaining why a value-added tax would be very bad for the United States, mostly because it would encourage and enable a much bigger burden of government spending.

That argument is compelling when I’m speaking to conservatives (though not all of them, apparently!), but I need different arguments when talking to my friends on the left.

Fortunately, I now have some very persuasive data that hopefully will make left-of-center types much less likely to support a VAT.

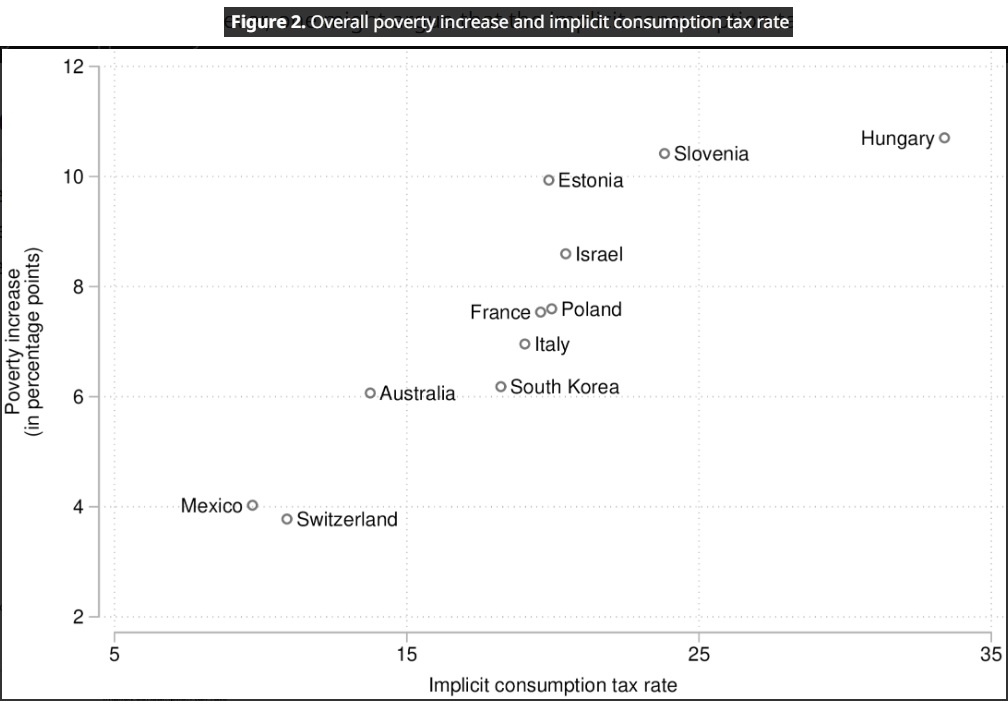

Look at this graph, which clearly shows a strong relationship between higher value-added taxes and higher poverty.

The chart comes from a recent study by Manuel Schechtl for Social Policy and Society, published by Cambridge University Press.

He investigated the extent to which valued-added taxes push households into poverty.

Poor households spend a higher share of their disposable income on consumption simply because consumption does not increase proportionally with income. …This study aims to evaluate the change in poverty rates before and after deducting consumption taxes (consumable income poverty) and the increase in poverty (consumption tax induced poverty) across household types. …Figure 2 indicates the overall percentage point increase in poverty plotted against the implicit consumption tax rate. The pattern reveals a clear positive association between consumption tax and poverty increase – for instance, consumption taxes in Slovenia and Hungary lead to an increase in poverty of over ten percentage points compared to about four percentage points in Mexico or Switzerland (which have lower implicit consumption tax rates).

Very depressing findings, at least for those of us who don’t like high taxes.

But there is a big methodological flaw in the study.

It relies on a dishonest definition of poverty, one that is used by ideologues who want to exaggerate societal problems.

…poverty is measured as below fifty percent of median disposable household income.

For what it is worth, this approach measures the distribution of income in a society, not material deprivation or some other tangible definition of actual poverty.

Having pointed out this flaw, I don’t know if the author is trying to be dishonest. He may have simply relied on data from a group (like the OECD) that does have a dishonest agenda.

However, this methodological flaw does not undermine Schechtl’s core point. There’s no question that value-added taxes reduce the ability of poor people to consume. And I would not be surprised if a chart based on honest data looked very similar to the one shown above.

The moral of the story is that all good people – on the right and on the left – should reject the value-added tax.

P.S. One of the reasons I get upset about the Biden/Trump approach to entitlements is that I fear it would make a VAT more likely.