People who understand “public choice” are usually not very optimistic about the future of economic liberty.

Simply stated, we recognize that politicians have an incentive to hook people on the “heroin of government dependency.” And that doesn’t end well.

But I don’t want to be too fatalistic. Every so often, we get policy makers who advance free markets, either for ideological or political reasons.

That’s what happened in the late 1900s, triggered by leaders such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

Sadly, it didn’t last.

Let’s look at an article by Antara Haldar, published by Project Syndicate. The author, a Professor of Empirical Legal Studies at Cambridge, wants readers to believe that the era of free markets is over.

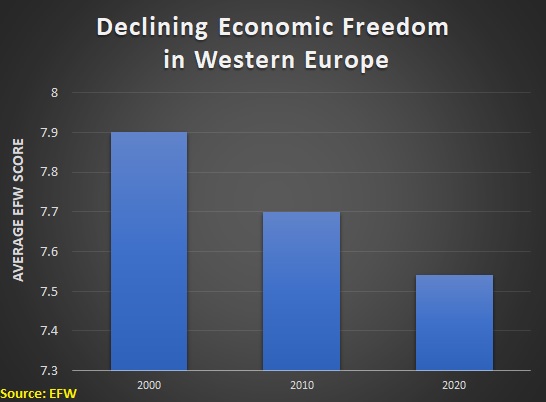

Given the mediocre-to-bad policies of the Bush/Obama/Trump/Biden years, as well as the gradual erosion of economic freedom in Western Europe, one can certainly make an argument that economic liberty is diminishing.

But that’s not the author’s point. She’s trying to argue that free markets are diminishing because such policies have failed.

Half a century ago, the “Chicago Boys” embarked on an experiment in Augusto Pinochet’s post-coup Chile that would become the dominant economic-policy framework of our time, introducing a raft of radical measures inspired by the ideas of Milton Friedman and the rest of the Chicago School. These ideas – born of an absolute faith in markets and an equally absolute suspicion of government – went on to rule the economics discipline and, more importantly, economic policymaking for the next 35 years. Not until the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, soon followed by the global financial crisis, did the Chicago School’s ascendancy end.

I sputtered with disbelief at the final sentence above.

The global financial crisis was caused by bad government policy, with monetary policy and housing subsidies at the top of the list (and don’t forget the TARP bailout, which was a bad government policy in response to a crisis caused by the other bad government policies).

Let’s dig deeper in the author’s argument. Here’s an excerpt about the era when free markets were in the ascendancy,

Following the stagflation of the 1970s, which amounted to a crisis for Keynesianism, Friedman’s prescription of disciplining government spending and freeing markets through deregulation and trade liberalization was carried out widely. It was implemented not only in Chile but also in the United States under President Ronald Reagan and the United Kingdom under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. Moreover, the same policies were also introduced – some might say imposed – globally through the Washington Consensus: a package of free-market measures pushed on developing countries.

This is a reasonable depiction of what happened, including the mention of the “Washington Consensus.”

But what follows does not make sense. Ms. Haldar wants readers to believe that free enterprise is an inadequate system because people don’t always make rational decisions.

But what if many of the biggest problems confronting the global economy have been misdiagnosed? …While Friedman’s account of self-equilibrating markets involved economic agents whose features were largely implicit, …Lucas’s model makes explicit the idea that we are all constantly processing large volumes of information to maximize our own welfare for any given economic context. Yet behavioral economics…has shown the “rational actor” to be a chimera. …individuals’ and firms’ actions routinely deviate from economic rationality. …Where does this leave the economic orthodoxy of the past 50 years? The prognosis is not good. With one foot already in the grave, the Chicago School’s remaining exponents would do well to reckon with its gory Chilean origin story. If neoliberalism’s core assumptions bear no resemblance to real-world outcomes, economists owe it to themselves – and above all to the public – to acknowledge its true nature.

I certainly agree that people are not always rational, but why does that somehow weaken the attractiveness of free enterprise compared to the various strains of statism?

If anything, it should make economic liberty even more attractive since there’s a feedback mechanism that rewards smart choices and punishes bad choices.

I’ll close by noting that the “Chicago School” sometimes uses theoretical models with assumptions such as perfect information, rational choices, and zero transaction costs. But that doesn’t mean advocates think that’s a description of the real world. They just want to set those factors to the side when explaining something else.

That being said, I think the “Austrian School” often offers a better way of thinking about economics.