Since I’m a big fan of spending caps in Switzerland and Colorado, I’m always on the lookout for research and analysis about fiscal rules.

For instance, there are pro-spending-cap studies from left-leaning bureaucracies such as the International Monetary Fund (here and here) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (here and here). There are also similar studies from the European Central Bank (here and here).

We can now add to that research with a new working paper from Switzerland’s Federal Finance Administration.

Authored by Thomas Brändle and Marc Elsener, it’s a very helpful review of different fiscal rules.

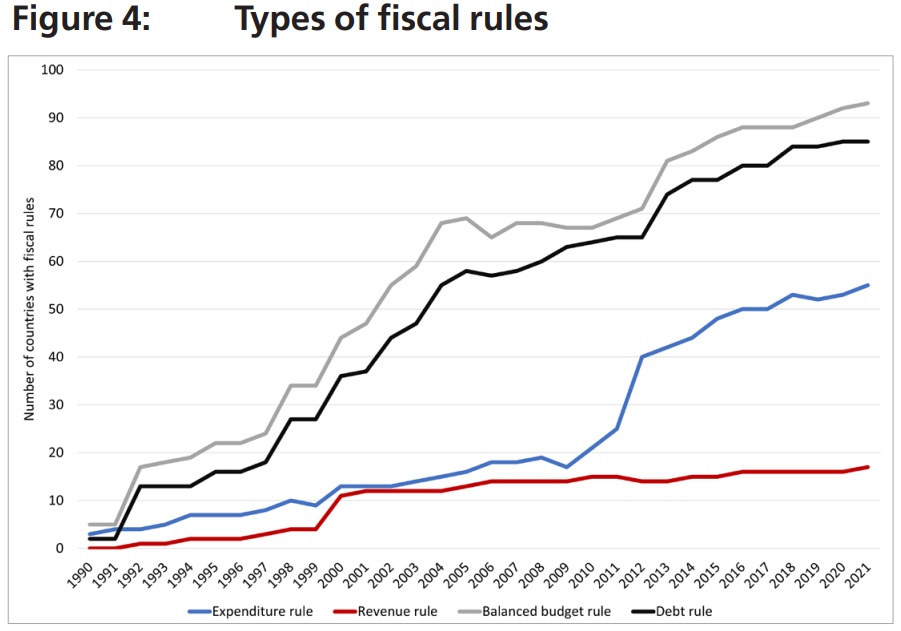

Let’s start by sharing a chart from the study on the number of fiscal rules. As you can see, the most dominant types of rules are anti-deficit (gray line) and anti-debt (black line).

Since I don’t think those rules are very effective, I’m more encouraged by the growing number of expenditure rules (blue line).

Here are some of the findings from the report.

A rich empirical literature investigates the impact of fiscal rules. First, the focus is on surveying recent studies that investigate the relationship between fiscal rules and “traditional” fiscal performance measures, such as public debt and budget balances. …For EU countries and the period 1990-2012, Nerlich and Reuter (2013)…find that the introduction of fiscal rules is related to lower public expenditures as well as to lower revenues. As the impact on revenues is smaller, the primary balance improves. This impact is stronger when fiscal rules are enacted in law or constitution and supported by independent fiscal institutions and effective medium-term expenditure frameworks. Fiscal rules have the strongest limiting impact on social spending, compensation of public employees.

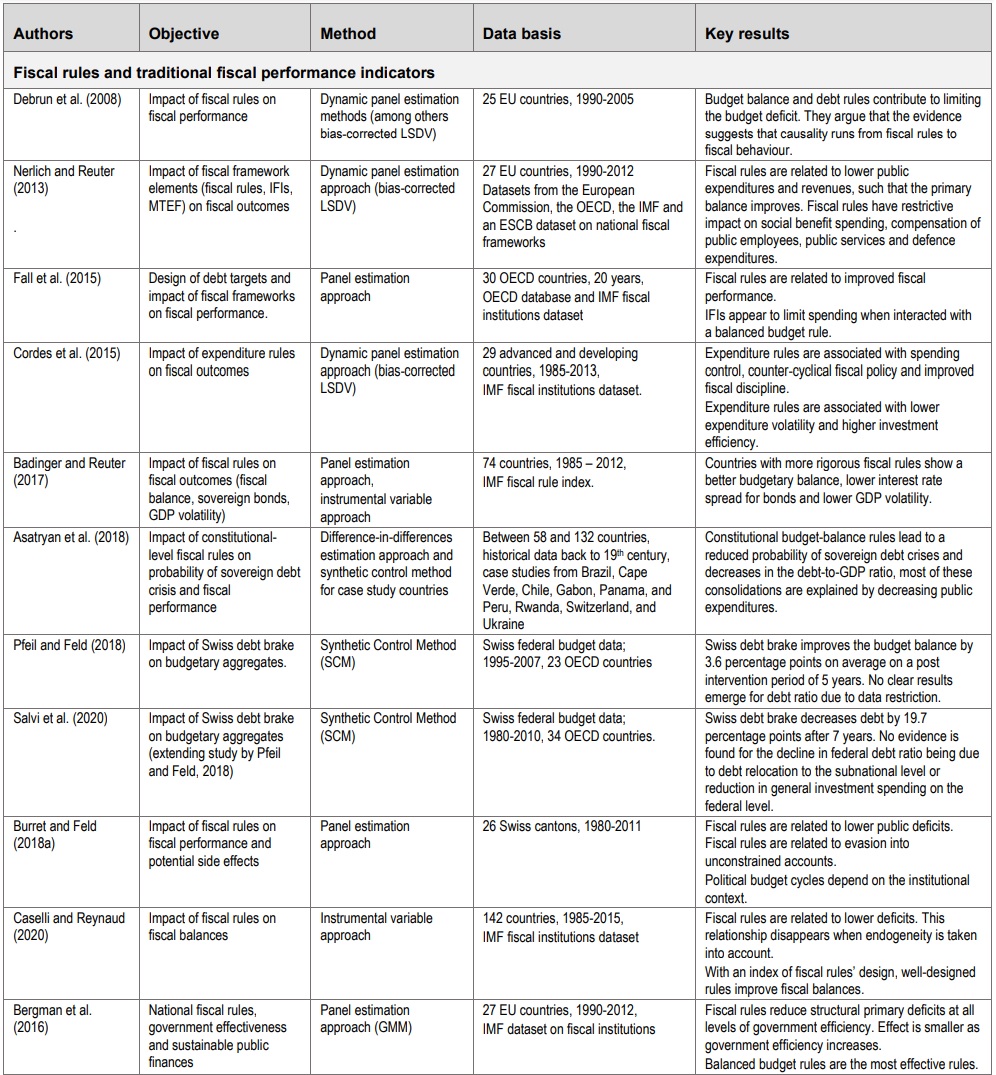

Here are some additional studies that are cited in the paper.

Based on a panel of 30 OECD countries, Fall et al. (2015) find that fiscal rules are related to improved fiscal performance. In particular, a budget balance rule appears to have a positive and significant effect on the primary balance and a negative and significant effect on public spending. Expenditure rules are associated with lower expenditure volatility and higher public investment efficiency. …Focusing on expenditure rules, Cordes et al. (2015) present an analysis for 29 advanced and developing countries for the period 1985–2013. Using a dynamic panel estimation approach, the analysis shows that these rules are associated with better spending control…and improved fiscal discipline. …Asatryan et al. (2018) study whether constitutional-level fiscal rules – expected to be more binding – impact fiscal outcomes. …they find that the introduction of a constitutional balance budget rule leads to a lower probability of sovereign debt crisis. For their most preferred sample of 132 countries between 1945 and 2015, they find that the debt-to-GDP ratio decreases by around 11 percentage points on average with constitutional balance budget rules. Most of these consolidations are explained by decreasing expenditures rather than increasing tax revenues.

I’m most interested in controlling the burden of government spending.

For my friends who are mostly fixated on red ink, it’s worth noting that Switzerland’s spending cap – which took effect in 2003 – has caused a dramatic shift from rising debt to falling debt.

Debt did increase during the pandemic, of course, but Switzerland’s debt increase was very small compared to the United States.

And Swiss lawmakers will now be required to impose additional spending restraint to make up for that extra red ink.

Needless to say, there is no similar “clawback” requirement in the United States.

I’ll close by sharing this table from the study, which summarizes the recent academic research on fiscal rules.

My takeaway from all this research is that spending restraint is the only practical solution to protect against “goldfish government.”

Especially given the demographic changes that are making modern-day welfare states unsustainable.