I have repeatedly explained that spending restraint is good fiscal policy.

And I have specifically explained that you achieve this goal by limiting spending so that it grows slower than the productive sector of the economy.

A fringe benefit of spending restraint is that it has a proven track record of deficit reduction and fiscal balance.

By contrast, there are some people who think that balancing the budget is the best definition of good fiscal policy. Even if that means higher taxes.

In an article for the European Conservative, Sven Larson reviews these two different approaches.

…government needs to be fiscally responsible. This is a worthwhile goal in general…but what does it mean in practice? …There are commonly two definitions of what ‘fiscal responsibility’ means. Depending on which one we adopt, we get very different policy results in the other end: That government should concentrate its spending only to a set of core functions; or That government needs to balance its budget. In theory, these two definitions are not mutually exclusive, but in practice, they tend to crowd out one another.

In Europe, Sven explains the balanced-budget approach is dominant.

Europe has long suffered from a political consensus on government spending. …it is practically unheard of that conservatives anywhere in Europe raise questions about the welfare state and its role in society. …everyone from the far left to the far right accepts that government consumes 40-50% of the economy, and that 80% of that spending furthers a socialist agenda of economic redistribution. …A key reason for this is the implicit acceptance of ‘fiscal responsibility’ as meaning that government should not run excessive deficits. …there is no mention of the critical tie between the size of government and Europe’s perennial economic stagnation.

He then shows how that stagnation leads to very worrisome trends – and that tax increases don’t solve the problem.

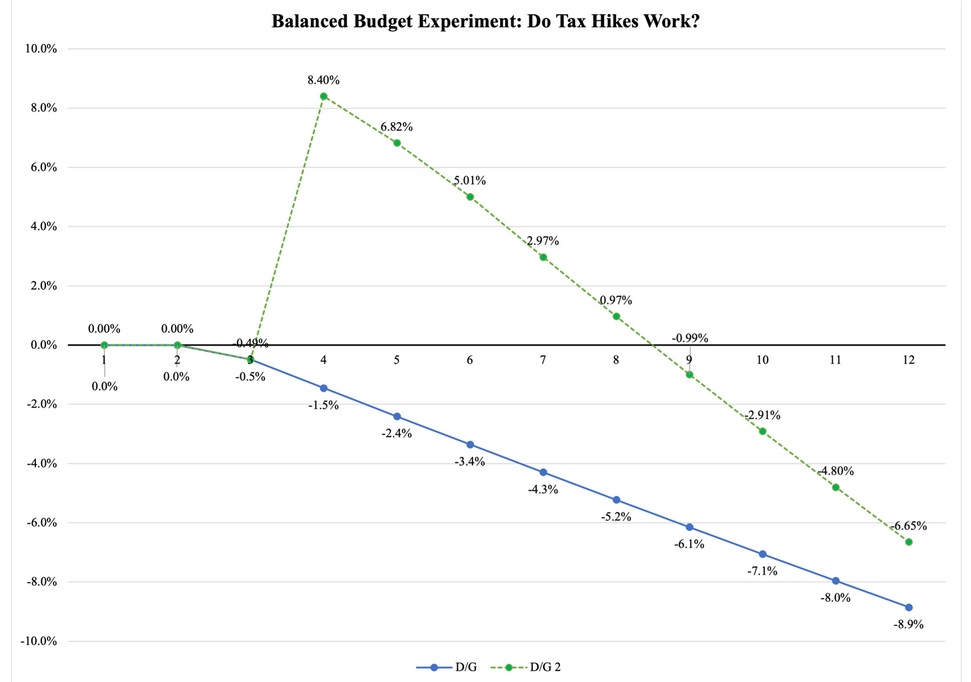

…let us do a little experiment. …Suppose…that there is a slowdown in economic growth. In the third year of our time line it falls from 3% to 2.5%, and then to 2%, where it remains for the rest of the 12-year period. …Since tax rates are unchanged, government collects less tax revenue—they decline with GDP. …Government spending, on the other hand, does not decline. The welfare state has made spending promises to people… These promises of entitlement benefits are statutory and morally written in stone. …In short: we have a budget deficit. …Suppose now that the legislature decides to be fiscally responsible. They raise taxes in the third year, which leads to a boost in tax revenue in the following year. …The problem with this scenario is that the tax hikes have a depressing effect on the economy. Growth slows down further, to 1.5% in the fifth year and 1% from thereon. This depresses tax revenue; the budget surplus dwindles rapidly until the budget goes into the red again. …the post tax-hike surplus goes away is the decline in GDP growth that the tax hikes cause.

Here’s his chart, which shows that tax increases may initially raise revenue, but that revenue tends to dissipate because the economy grows slower.

Sven’s conclusion is very accurate.

…we have two ways to define what it means to be fiscally responsible: to balance the government budget or to shrink government spending. The former does not lead to the latter, but the latter facilitates the former.

Amen. The balanced-budget-über-alles approach is a recipe for tax increases. Simply stated, those tax increases don’t produce good results. And that’s an understatement.

Whenever I debate supposed conservatives who think higher taxes can somehow solve our fiscal problems, I acknowledge that tax increases theoretically could be acceptable if matched by spending reforms.

But that type of deal doesn’t exist in the real world. So I then ask them to look at these two charts and ask if they have any evidence in the other direction. I don’t know if it changes their minds, but I always win the debate.

P.S. The gold standard for good fiscal policy is Switzerland’s spending cap.

———

Image credit: 401(K) 2012 | CC BY-SA 2.0.