The best evidence for spending caps is the comparison between the United States and Switzerland.

Even since Swiss voters overwhelmingly imposed their “debt brake” on politicians 20 years ago, total government spending in Switzerland has increased by an average of just 2.2 percent per year.

In the United States, by contrast, total government spending has grown more than twice as fast – an average of 4.9 percent per year – over the same time period.

But there is also some evidence for spending caps from the United States. Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute has a new study on spending caps that have periodically existed in the United States.

They have only applied to discretionary spending (click here to understand the federal government’s different budget categories), so they are not as extensive as the Swiss spending cap.

Nonetheless, Brian’s chart show that they have produced dramatically better results.

Here’s some of Brian’s analysis.

…spending caps that accommodate realistic appropriations growth rates have sustainably reduced discretionary spending as a share of the economy. …Because spending caps can be easily repealed at any time, they cannot force spending cuts beyond the political system’s capacity. They can only enforce an existing broad commitment to constrain spending. …while discretionary spending has not been the driver of rising long-term deficits—and cannot realistically be cut deeply enough to accommodate surging mandatory costs—Congress should still approach this spending with a “do no harm” principle, ensuring that it does not rise as a share of the economy… Cap enforcement is a challenging needle to thread. If caps are too tight and rigid, they will be repealed. If they are too loose and have countless off-ramps, they will cease to limit spending. The optimal solution is a bend-but-not-break approach that keeps caps realistic and flexible yet difficult to evade entirely. This means imposing caps that cover as many discretionary appropriations as possible.

The most fascinating part of Brian’s paper is a look at what happened the last two times there were spending caps.

The original spending caps from the 1990 budget were not overly effective, but the election of a Republican Congress in 1994 led to several years of genuine spending restraint.

Unfortunately, that fiscal discipline evaporated in the late 1990s/early 2000s.

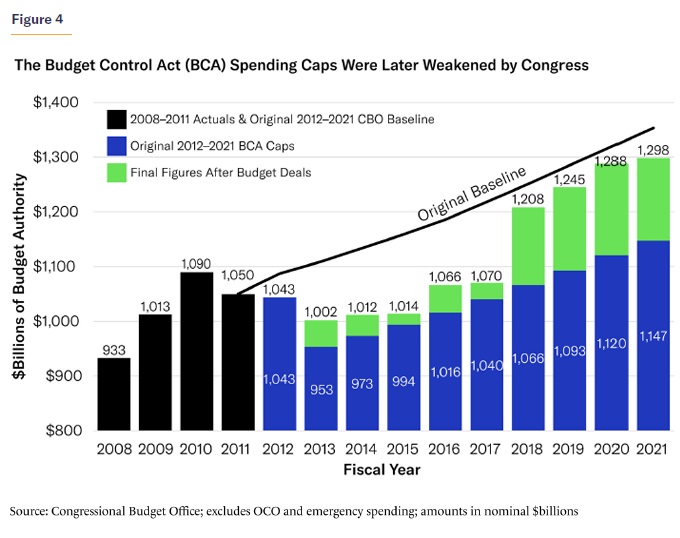

Next we have Brian’s calculations from the Budget Control Act, which was imposed after the late Bush/early Obama spending orgies.

The good news is that the spending caps initially were very effective (helped substantially by a sequester). The bad news is that Trump then allowed another spending orgy (which Biden has continued).

I’ll close by agreeing and disagreeing with Brian’s analysis about the desirability of tight spending caps.

He argues in his paper that politicians will rebel if they are forced to be genuinely frugal (such as a hard spending freeze).

Real-world evidence shows he is right, so that part is correct. I wonder, though, if Brian is being too optimistic in assuming that weaker spending caps would be obeyed.

My fear is that politicians will take advantage of any excuse to overspend, regardless of whether they have been frugal or profligate leading up to that time.

But let’s not digress. The main lesson from his paper is that spending caps work. Our challenge is figuring out how to get shallow and selfish politicians to do the right thing (enact caps) and obey the right thing (comply with caps).

P.S. If you are skeptical of Brian’s analysis, there are pro-spending-cap studies from left-leaning bureaucracies such as the International Monetary Fund (here and here) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (here and here). There are also similar studies from the European Central Bank (here and here).

———

Image credit: pxhere | CC0 Public Domain.