Back in 2016, here’s what I said about the debt limit during some congressional testimony (and I made very similar points in some 2013 testimony).

Near the end of my testimony (about 4:55) I discuss “prioritization,” which is what would happen if the debt limit is not raised and the Treasury Department has to decide which payments are made (and which payments are delayed).

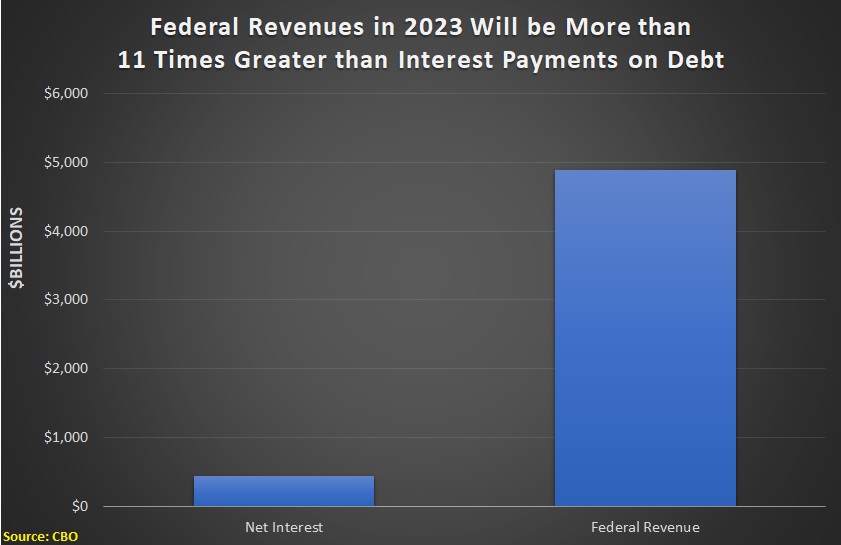

I then pointed out that federal tax revenues in 2017 were expected to be 11 times greater than annual interest payments.

As such, there obviously would have been plenty of cash available to make interest payments, as well as to finance other economically or politically sensitive items (I assume, for instance, that Treasury would have prioritized monthly Social Security benefits as well).

Would this have been messy? Yes. Would it have been uncharted territory not covered by the law? Yes. But would it have been better than default, which would have caused turmoil in financial markets? Another yes.

Which now brings us to the present day. We’re now in another debt limit fight, so I decided to look at the most-recent data from the Congressional Budget Office to see whether the federal government will still have plenty of cash so that interest payments on the debt can be prioritized.

Lo and behold, annual tax revenue this fiscal year is going to be more than 11 times greater than annual interest payments. Just like in 2017.

In other words, we presumably can sleep easy. There’s plenty of money to pay interest on the debt.

There would only be a default if Joe Biden or Janet Yellen (the Treasury Secretary) deliberately chose not to prioritize. And the odds of that happening presumably are way below 1 percent.

Some people may wonder why we should accept even that small risk? Why not simply increase the debt limit so that the odds of a default are 0 percent?

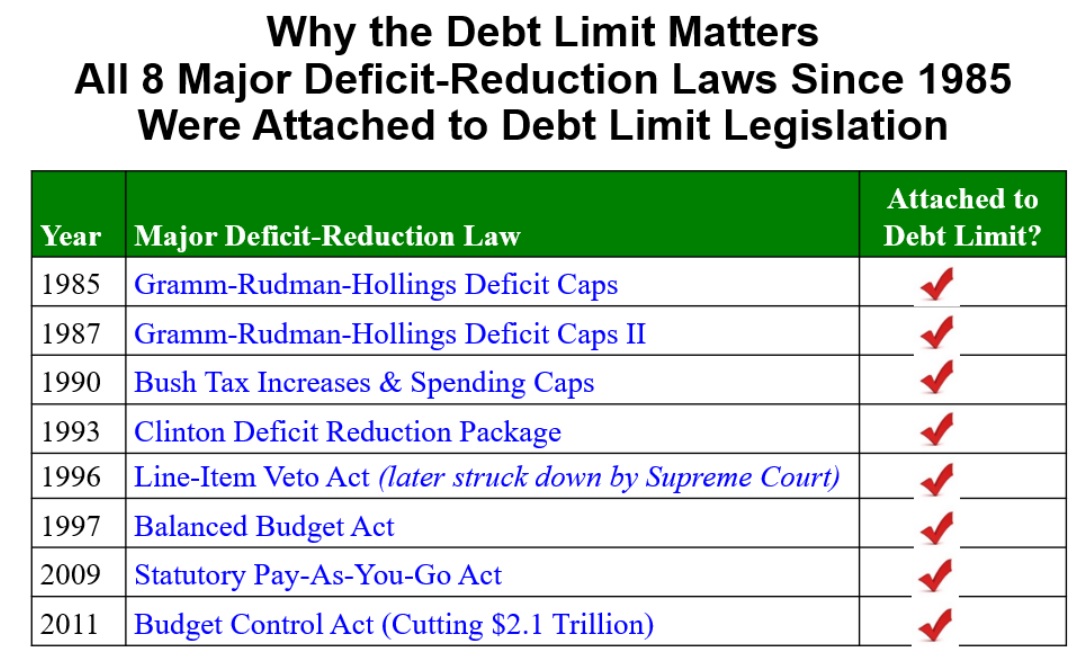

That’s a fair point, but it must be balanced by the recognition that the United States is on a path to long-run economic and fiscal chaos. So I can also understand why some lawmaker say the debt limit should only be raised if accompanied by some much-need spending restraint.

And, for those who care about real-world evidence, that’s what has happened in the past. Indeed, Brian Riedl notes that it’s the only plausible vehicle for altering the nation’s fiscal trajectory.

I’ll close by expressing pessimism that House Republicans will achieve anything in the current fight over the debt limit.

We won’t get something really good, like a spending cap. But I start with very low expectations, so I guess I’m happy that Republicans are at least pretending to care once again about excessive government spending.

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a first step!

P.S. I partially disagree with Brian Riedl’s list. The 1990 Bush tax increase was not a “deficit-reduction law.” And it was post-1994 spending restraint that produced a balanced budget, not Clinton’s 1993 tax increase.

P.P.S. Remember that debt is bad, but it should be viewed as a symptom. The underlying disease is excessive government spending.

———

Image credit: Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy University of Michigan | CC BY-ND 2.0.