Back in April, I warned that European governments were spending too much, sewing the seeds of another fiscal crisis (aided and abetted by the European Commission).

Let’s expand on that issue today, focusing specifically on the eurozone (the European nations that use the euro currency).

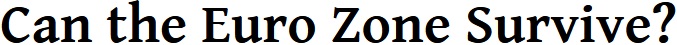

Here’s some OECD data on the burden of government spending in the major euro-using countries.

That’s a depressing chart. All of those nations are far above the growth-maximizing size of government.

But a fiscal crisis doesn’t happen simply because a country has too much government. It also matters how much of the spending burden is financed by borrowing. And much existing debt there already is.

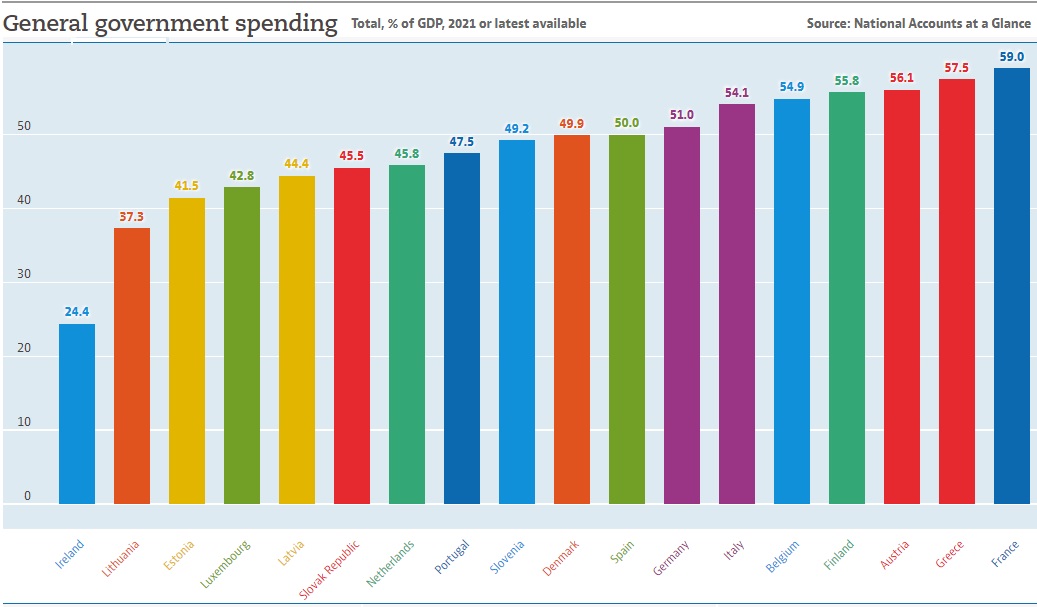

Speaking of which, here’s some OECD data on existing government debt in those nations.

Greece and Italy have the biggest debt burdens, but France, Spain, Portugal, and Belgium also have debt levels above 100 percent of GDP.

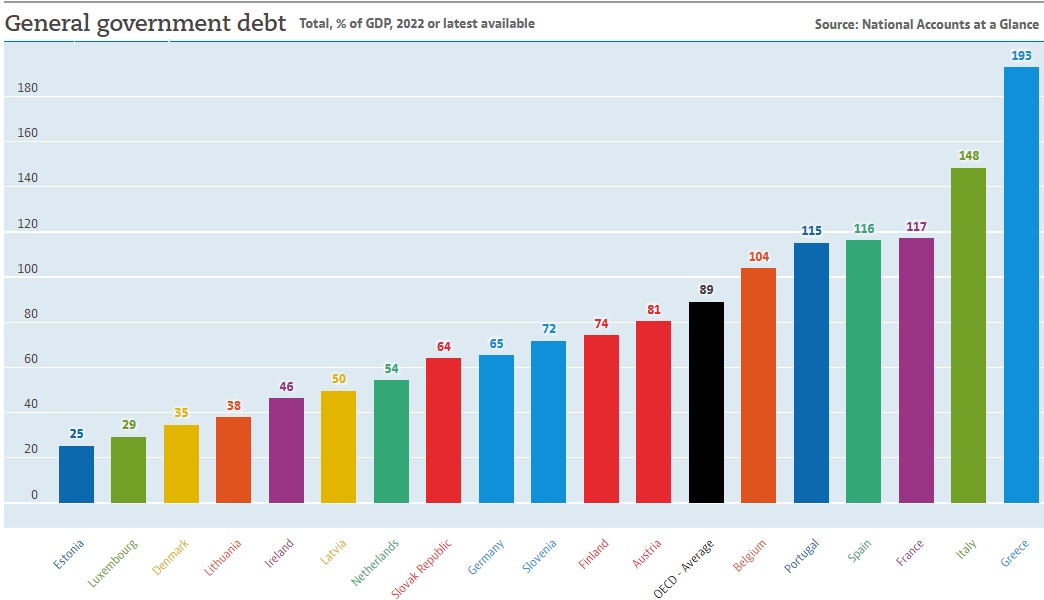

By the way, the future outlook also matters.

On that basis, Europe is in even greater danger, largely thanks to entitlements and demographics.

The OECD does not have country-specific projections of future debt, but here’s a chart from that bureaucracy’s recent Economic Outlook. It shows a 60 percent increase in debt for OECD governments over the next two decades.

I’m guessing a chart for eurozone nations would also show a big increase in debt levels (just like we saw a big jump last decade).

It is very likely that all the new spending and all the new debt will produce bad results.

Here are some excerpts from Desmond Lachman’s article in National Review.

Some 25 years after launching the euro, there has been continued divergence between the public finances and economic performances of the euro zone’s northern members and its southern periphery. While Germany and the other northern member countries have enjoyed prosperity and generally pursued responsible budget policies, income levels today in countries like Greece and Italy are practically unchanged from where they were some 15 years ago. Meanwhile, public-debt levels in the euro zone’s economic periphery have risen to record highs. …there is every reason to think that economic divergences will be exacerbated. That will raise new questions about the euro’s survivability once the European Central Bank (ECB) finally ends its bond-buying activities.

He’s right about the pernicious role of the European Central Bank.

That bureaucracy enabled more spending and more debt, and that means an ever bigger bubble that will cause more damage when it bursts.

And Lachman writes that it’s a matter of when, not if.

Up until last year, high public-debt levels were not of much concern when interest rates were low and when the ECB was buying massive amounts of bonds to support the euro zone economy. However, those days are long gone. In the wake of the recent inflation spike, the ECB…is about to finally end its bond-buying program. That will substantially increase the cost of rolling over the large amount of public debt that will come due next year. All of this makes it all too likely that it is a question of when — and not if — we will have another round of the European sovereign-debt crisis.

For what it’s worth, I think he’s right about another debt crisis.

And Italy will probably be where it starts.

P.S. While the European Central Bank has contributed to the problem, the European Commission also has enabled more profligacy.

As originally envisaged…, the euro zone contained no provisions allowing for rescues financed from within the currency union. This was designed to stop the historically less fiscally responsible members from free-riding… But it did not work out… To avoid taking the currency union into territory where one or more of its members might default, the euro zone (after adopting various ad hoc financing mechanisms and participating in a number of bailouts) now has institutionalized an emergency-funding regime.

P.P.S. The Maastricht criteria failed in part because they targeted the wrong variable.

In an effort to ensure responsible budget policies, the euro zone adopted the so-called Maastricht criteria, which were meant to guide each country’s budget policy. Members were supposed to restrain their budget deficits to no more than 3 percent of GDP. They were also supposed to bring their public-debt levels down to 60 percent of GDP. It would be an understatement to say that the Maastricht criteria have been observed in the breach. …Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain…all had budget deficits in excess of 3 percent of GDP and public-debt-to-GDP ratios exceeding 100 percent.

The right solution is a Swiss-style spending cap, and even the German government seems to understand that’s the right approach. And if some nations don’t want to adopt this solution, they should be allowed to default.