At the risk of oversimplifying, here’s the three-sentence trajectory of Chinese economic policy.

- Crippling communist failure and suffering under Mao.

- Partial reform during the “Washington Consensus” era.

- Backsliding to more statism under President Xi.

So what’s all that mean? Well, when you start with awful policy, then take a few steps in the right direction, only to then move back in the wrong direction, you probably won’t be an economic powerhouse.

And that’s exactly what we see in the data.

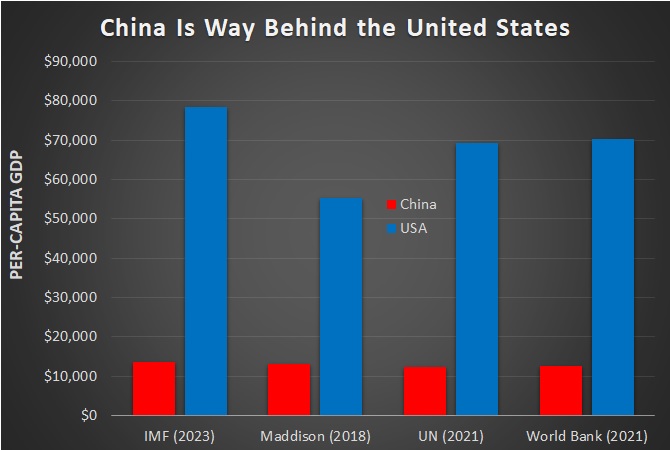

Here’s a chart showing that there is a huge gap between per-capita economic output in the United States and China. And that gap exists whether we rely on data from either the IMF, Maddison,* the UN, or World Bank.

That chart is the bad news (and it may be even worse than shown in the above data).

The good news is that China is no longer a miserably poor nation, like it was during the fully communist years under Mao.

But it also looks like China will never become a rich nation.

Especially when the government penalizes success. Which has very negative effects, as reported by the Economist.

Regulatory crackdowns have devastated once-thriving sectors like private education. Officials rage against “money worship”… China’s wealthy…have been looking to leave. …in 2022 some 10,800 high-net-worth individuals, who have an average wealth of $6m, left the country, with the flow accelerating at the end of the year as covid controls eased. …Even more are expected to leave in 2023… In recent years, Singapore has been favoured. The city-state is the top destination for Chinese billionaires considering emigration… According to data from Singapore’s central bank, …it is likely that as many as 750 Chinese family offices were registered in Singapore.

Needless to say, it’s not a good sign when the geese with the golden eggs are flying away.

That being said, the problems in China go well beyond class warfare.

The country has a major problem with cronyism (a.k.a., industrial policy).

But I’ve written many times about that issue, so let’s look at another example of China’s bad policy. Li Yuan has an article in The New York Times about wasteful spending and excessive debt in the nation’s cities.

As part of the ruling Communist Party’s all-in push for economic growth this year, local governments already in debt from borrowing to pay for massive infrastructure are taking on additional debt. They’re building more roads, railways and industrial parks even though the economic returns on that activity are increasingly meager. …China’s local governments…are in fiscal disarray. …According to official data, China’s 31 provincial governments owed around $5.1 trillion at the end of 2022, an increase of 66 percent from three years earlier. An International Monetary Fund report puts the number at $9.5 trillion, equivalent to half the country’s economy. …China is full of wasteful infrastructure that the government likes to brag about but that doesn’t serve the most urgent needs of the public. …The Chinese government likes to say the country has the longest and fastest high-speed railways in the world. But…most lines operate below capacity and at a great loss.

Sounds like Amtrak, but on steroids.

The bottom line is that China’s economy is both weak and fragile.

Which is unfortunate. A thriving China presumably is more likely to be a friendly China.

* The Maddison data is for 2018, and uses $2011 dollars rather than current dollars, which explains why it seems significantly different than the other sources.

P.S. Rather than invade Taiwan, China should copy its economic policies. Or copy the policies of other better-performing Asian Tigers. Heck, the recipe for prosperity is not complicated.

———

Image credit: judithscharnowski | Pixabay License.