In mid-2021, I wrote about long-run policy lessons from the coronavirus pandemic.

That column focused on insights from my five-part series (see here, here, here, here, and here) about the failure of big government.

More specifically, the CDC and FDA did a terrible job domestically and the WHO did a terrible job internationally.

By contrast, millions of lives were saved by the private sector.

But we also learned fiscal policy lessons in addition to public health lessons.

The most depressing fiscal lesson is that politicians love having any excuse to spend more money.

Though that’s hardly a surprise.

Now that we are in early-2023, are there more lessons to be learned? The answer is yes.

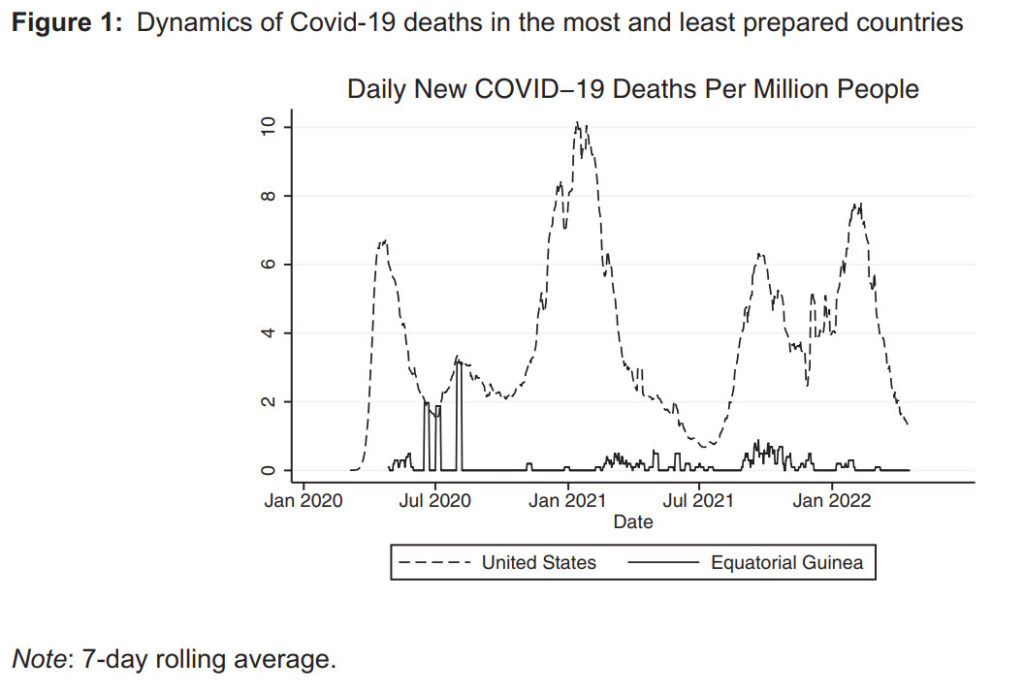

A new study by Professors Alex Tabarrok and Robert Tucker Omberg, published by the Oxford Review of Economic Policy, finds no relationship between supposed pandemic preparedness and health outcomes.

How effective were investments in pandemic preparation? We use a comprehensive and detailed measure of pandemic preparedness, the Global Health Security (GHS) Index produced by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHU), to measure which investments in pandemic preparedness reduced infections, deaths, excess deaths, or otherwise ameliorated or shortened the pandemic. We also look at whether values or attitudinal factors such as individualism, willingness to sacrifice, or trust in government—which might be considered a form of cultural pandemic preparedness—influenced the course of the pandemic. Our primary finding is that almost no form of pandemic preparedness helped to ameliorate or shorten the pandemic. Compared to other countries, the United States did not perform poorly because of cultural values such as individualism, collectivism, selfishness, or lack of trust. General state capacity, as opposed to specific pandemic investments, is one of the few factors which appears to improve pandemic performance.

The study is not free to access, but Professor Tabarrok cited it at Marginal Revolution and shared this chart comparing death rates in the (allegedly) best prepared nation and the least prepared nation.

The Omberg-Tabarrok study shows us that pre-pandemic government policies were ineffective.

What about government policies once the pandemic hit?

In a column for the Washington Times, Richard Rahn points out that heavy-handed government intervention also was ineffective.

Sweden had the lowest aggregate excess mortality percentages (2.79)… Sweden was unique in that it had the fewest “lockdown” requirements, while countries like the U.S., with substantial lockdowns, had much higher excess deaths. We also know that within the U.S., states with very onerous lockdown requirements, like New York, have total age-adjusted higher death rates than states like Florida with few lockdown requirements. The big mistake the CDC people (Dr. Anthony Fauci, Dr. Francis Collins, etc.) made was to single-mindedly focus on potential deaths directly from COVID-19 while largely ignoring the potential deaths indirectly induced by the lockdowns. …Other studies support the evidence of health harm to people who have not yet died but are likely to have their lives shortened by the indirect effects of the lockdowns. …If the above-described mistakes had not been made, it is no overstatement to say that hundreds of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars could have been saved.

The information about Sweden is worth noting.

But the biggest lesson from Richard’s column is that politicians and bureaucrats failed to consider direct and indirect effects (a problem that is sadly common with government), so their cost-benefit analysis (to the extent they did any) was very flawed.

And we also need to learn that it is depressingly easy for governments to curtail liberty.

———

Image credit: U.S. Army Photo | Public Domain.