As a long-time admirer of President Reagan and his economic policies, I was very pleased to author a new study for the Club for Growth Foundation entitled Reaganomics for the 21st Century.

In the report, I ask “Is it time for Reaganomics 2.0?”

This week, I’m going to look at key economic issues and see whether Reagan’s policies worked and whether similar policies are needed again today.

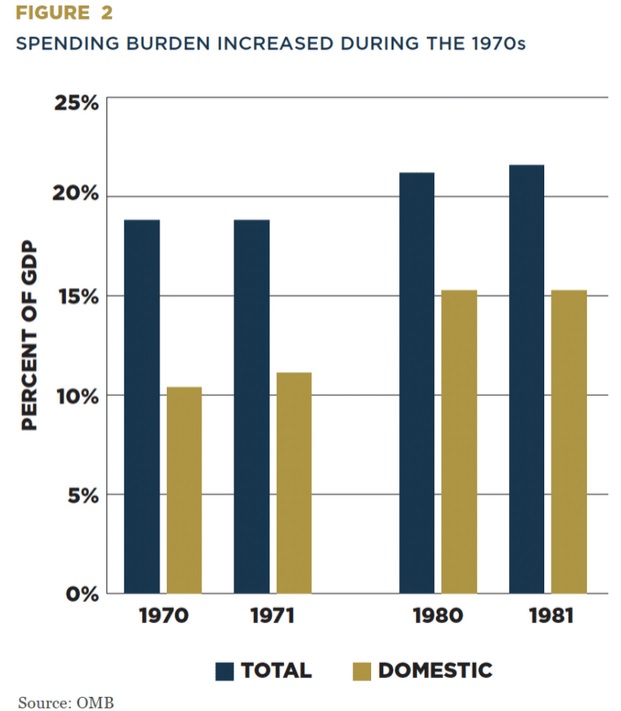

We’ll start with fiscal policy. Here’s Figure 2 from the study, showing that the burden of federal spending, measured as a share of economic output, increased significantly during the 1970s.

Most troubling, almost all of the increase was because of additional domestic spending.

What happened during the Reagan years? Did policy improve?

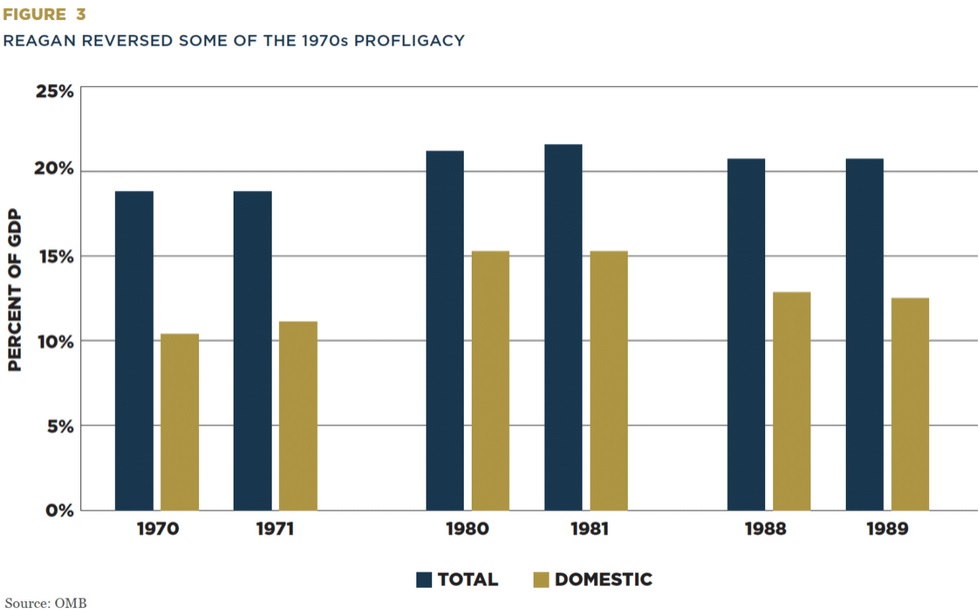

As you can see from this next chart, Figure 3, Reagan reversed that worrisome trend. The burden of government spending fell during his years in office (Reagan’s budgets covered 1981-1989, but I also included 1980 and 1988 for people who focus on election years).

Most impressively, Reagan reduced the burden of domestic spending (both entitlements and discretionary) by 2.5 percentage points of GDP.

For those who want more information on Reagan’s successful spending restraint, I recommend this 2011 video.

The purpose of today’s column, though, is to focus on the future. Specifically, what are the challenges we face today and would a Reagan-style approach be appropriate?

The first part of that question is easy to answer. The federal government is far too big and America’s fiscal burden is projected to become an even bigger problem in the near future.

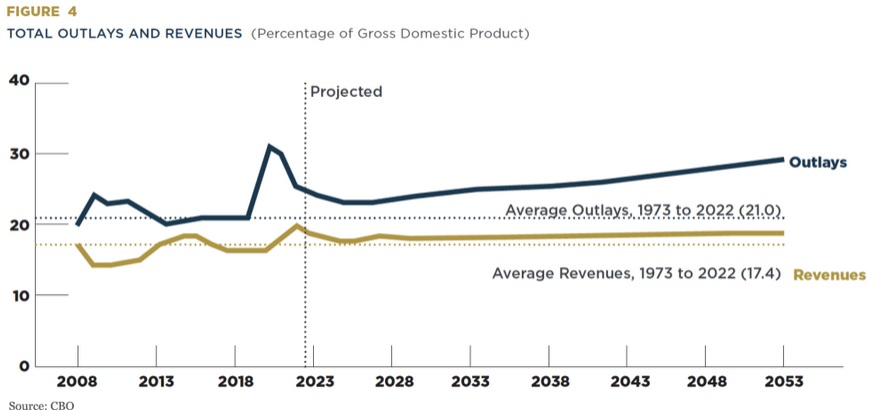

In the study, I included this chart from the Congressional Budget Office, which shows that the burden of federal spending is on a very bad upward trajectory over the next three decades.

The second part of the question also is easy to answer.

Reagan’s approach was to restrain spending and that same approach is needed today. Here’s some of what I wrote.

America’s spending problem today is worse than it was when Reagan was elected and inaugurated. The overall burden of spending has reached more than 24 percent of economic output and domestic spending by itself consumes more than 19 percent of GDP. …All this spending…undermines growth by diverting resources from the productive sector of the economy. …Domestic discretionary spending is a very ripe target for budget savings. …Entitlements are the major budget challenge. More than 70 percent of the federal budget is allocated to these programs, and that share will increase since entitlement spending is projected to become an even bigger burden in the future. …some sort of spending restraint would be desirable. One option is a…spending cap. The best model in the United States is Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights. The TABOR provision in Colorado’s constitution effectively limits spending so that it cannot grow faster than the combination of inflation plus population. …Globally, the best model is Switzerland’s spending cap.

In the study, I explain that domestic discretionary spending should be significantly reduced, including elimination of various departments and agencies.

And I also make the case for entitlement reform, including Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security.

To conclude this column, let’s look at the big picture.

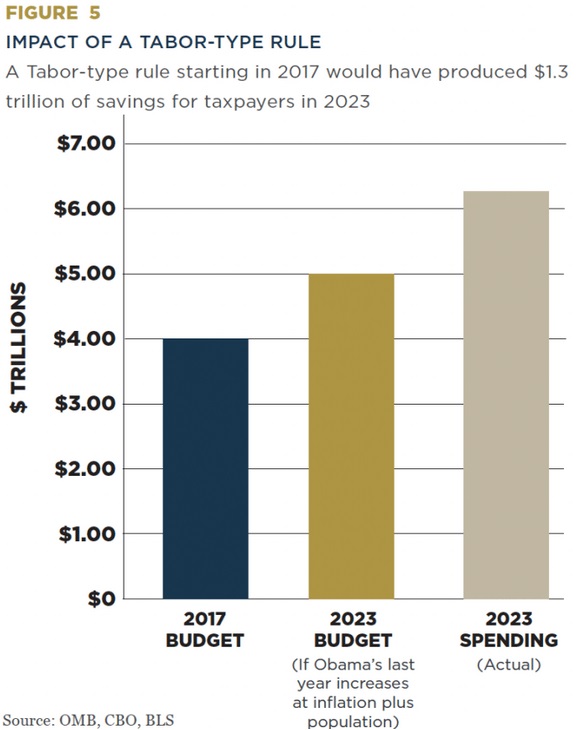

I wrote that some sort of spending cap is needed. To help make the case, I showed what would have happened to federal spending if Washington was subjected to a TABOR-style spending cap at the start of the Trump years.

As you can see in Figure 5. the savings would be enormous. Limiting spending increases to population plus inflation would have resulted in a federal budget of about $5 trillion for 2023, which is more than $1 trillion less than politicians actually spent.

The bottom line is that TABOR has produced big savings for Colorado taxpayers, but those numbers would be dwarfed by nationwide savings is Washington was constrained by a spending cap.

P.S. Politicians who oppose spending restraint implicitly support massive tax increases on lower-income and middle-class households.

———

Image credit: The U.S. National Archives | Public Domain.