I rarely write about the national debt for the simple reason that it is far more important to focus on the burden of government spending.

After all, improper spending saps economic vitality, regardless of whether it is financed with taxes, borrowing, or money printing.

But I’m writing about debt today because something very interesting has happened in the past few years.

From early 2020 to late 2022, profligate politicians increased the national debt by about $3 trillion, yet government debt actually declined when measured as a share of economic output.

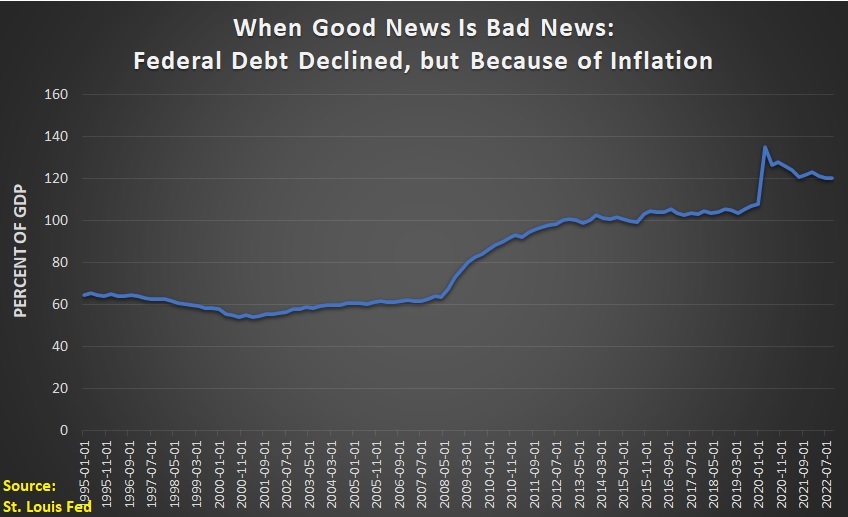

Here’s a chart from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, which shows that over the past couple of years that debt has dropped from nearly 135 percent of GDP down to about 120 percent of GDP.

So what happened? How can debt explode, yet the debt burden simultaneously fall?

There’s one good answer and one very bad answer.

The good answer is that the economy fell into a terrible recession when the Coronavirus pandemic first began. And since GDP was falling while deficit spending was skyrocketing, that explains why debt spiked upwards in early 2020.

But as that downturn has faded, overall economic output (GDP) has recovered. And because GDP increased during that period faster than debt increased, it means less debt as a share of GDP.

Which is partly what is shown in the chart.

But there’s also a bad reason. Irresponsible monetary policy has saddled the economy with high rates of inflation.

In the short run, as explained by Veronique de Rugy of the Mercatus Center, this has made the debt burden appear smaller.

Government debt as a share of the U.S. economy is falling. This must mean President Joe Biden’s administration and Congress are practicing fiscal responsibility, right? No, it doesn’t. The main driver behind the reduction is inflation… The missing debt is nothing to celebrate when it’s due to inflation, something especially harmful for poorer Americans who see their living standards erode. …the inflation, which came as a surprise to so many, …led to the decrease in the debt-to-GDP ratio. According to an International Monetary Fund (IMF) fiscal monitor study, in countries with debt-to-GDP over 50 percent, for every 1 percentage point of unexpected inflation, the debt ratio will be reduced by 0.6 percentage points. This perfectly explains most of the debt-ratio decline. …The Biden administration has inadvertently reduced the debt-to-GDP ratio. But it has done it in the worst possible way, refusing to heed warnings of an inflation debacle and instill some fiscal common sense. This has made the work of the Fed harder, if not impossible, and life more difficult for rich and poor Americans alike.

There’s some wonkiness in the above excerpt, but all you really need to know is that high rates of inflation can reduce the value of financial assets. Especially assets (like government bonds) that pay low rates of interest.

This is a form of financial repression.

And it only works in the short run. In the long run, inflation leads to higher interest rates (as we are now observing).

So any short-run benefits are more than offset by higher long-run costs. Sort of the monetary version of my Fourteenth Theorem of Government.

P.S. History shows us that there is a very successful recipe for reducing large debt burdens.

———

Image credit: pxhere | CC0 Public Domain.