In addition to discussing politicians and insider trading, I also was asked about antitrust laws during my recent CNBC appearance.

As you might imagine, I expressed skepticism about Biden’s plan for a more interventionist approach.

My view is that mergers should be governed by the market, not by politicians.

Especially when politicians have created a Catch-22 situation with antitrust laws.

Companies can be accused of improper behavior regardless of what they do.

- If they charge more than their competitors, that’s supposedly evidence of monopoly power.

- If they charge the same as their competitors, that’s supposedly evidence of collusion.

- If they charge less than their competitors, that’s supposedly evidence of predatory pricing.

Just like the poem from The Incredible Bread Machine.

For today, let’s focus on the specific issue of “consumer welfare,” which has limited the folly of antitrust policy by creating a presumption that mergers are okay if prices go down.

In a column for the Wall Street Journal last year, former Senator Phil Gramm and Mike Solon elaborated on this issue.

…over the past half-century, a bipartisan consensus has existed that antitrust law and enforcement should be anchored in consumer welfare. This consensus, beginning in the 1970s, was founded on a bipartisan rejection of Progressive-era regulatory frameworks that harmed consumers, competitiveness and economic growth. …The modern progressives who dominate the Biden administration..see the world through the lens of class warfare, as a zero-sum game. Like Progressives before them, they view the rule of law not as a cornerstone of liberty and democracy, but as an impediment to equality… Unlike most Americans, progressives view low prices as a problem, not a benefit. …With the consumer-welfare standard uprooted, antitrust would become a license to control the American economy, capriciously rewarding favored businesses and punishing disfavored ones.

Professor Brian Albrecht explained in National Review why politicians and bureaucrats should not abandon the consumer welfare standard.

U.S. courts and antitrust-enforcement agencies…, beginning in the 1970s, …turned toward economic reasoning to develop a consistent framework for determining antitrust violations. The result has been the elevation of consumer welfare as antitrust regulation’s fundamental concern. Based on this criterion, economic analysis is applied to business conduct alleged to be anticompetitive to determine the likely impact on consumers. Higher prices for goods or services, lower quality, or less output are the characteristic harms to be avoided. Unfortunately, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) under chairwoman Lina Khan wants to rewind the clock. …the commission will decide what is “unfair” based on whether the conduct might harm “competition, workers, or other market participants.” If that sounds extremely vague, it’s because it is.

Back in 2021, John McGinnis wrote about antitrust and consumer welfare for Law and Liberty.

The Biden Administration wants to transform antitrust law. In doing so, it would dispense with a four-decade-old consensus that the welfare of consumers should be the object of competition policy. This principle would be replaced with a mixture of untested economic ideas combined with a view that antitrust law should somehow advance democracy. …Not only will this vision harm economic efficiency, it will also make it easier for government officials to reward friendly companies and punish those who do not do the administration’s bidding even on matters unrelated to competition. …the Biden administration’s blunderbuss approach to antitrust law is not limited to tech, but represents a potentially new mechanism of government control over the commanding heights of the economy.

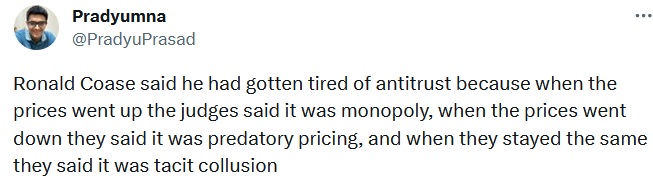

Here’s a tweet from Pradyumna Prasad about antitrust laws.

It’s akin to the above cartoon since it points out that government policies are so convoluted that a company can be guilty regardless of the prices it charges.

I mentioned in the interview that antitrust bureaucrats have a dismal and embarrassing track record. Jessica Melugin of the Competitive Enterprise Institute summarized some of the most famous mistakes back in 2021.

*Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States had a defendant that was cutting prices while increasing output. The case also lacked evidence of either predatory pricing or consumer harm. *U.S. v. American Telegraph and Telephone Company (AT&T) broke up a monopoly that was created by government, not the market. The case illustrates how regulatory capture—regulated entities’ influence over the regulatory process—works to create and maintain monopolies. *The U.S. v. International Business Machines (IBM) case lasted for 13 years before the Department of Justice (DOJ), which brought the suit, deemed it “without merit” and dropped it. The multi-million-dollar litigation inadvertently raised prices for IBM customers. *Finally, U.S. v. Microsoft illustrates how technological innovation moves faster than litigators.

In a column for the American Institute for Economic Research, Professor Don Boudreaux explains that antitrust laws were enacted because established firms were upset about bigger (and more efficient) rivals charging lower prices..

The post–Civil War transcontinental expansion of railways and telegraphy, along with other technological developments such as the refrigerated railroad car, markedly increased the scale on which many goods could be profitably produced and supplied. Entrepreneurial firms that took advantage of these economies of scale expanded outputs and lowered prices to unprecedented levels. While as a result consumers reaped massive benefits, many established producers suffered. Older, smaller, and less entrepreneurial firms could not match the low prices offered by their large-scale rivals. The demise of many familiar, small-scale producers along with the rise of unprecedentedly huge firms — and equally unprecedented personal fortunes — created the mirage of monopolization. This mirage was opportunistically exploited by some producers who could not match the lower prices of newer and larger rivals. …This animus, in the late 19th century, of smaller-scale producers against their upstart, large-scale, and more efficient rivals supplied the fuel for antitrust legislation, first at the state level and soon afterward at the national level.

In other words, antitrust laws are a product of “public choice” incentives. Politicians always come up with excuses to grab more power.

P.S. You won’t be surprised to learn that Robert Reich does not understand antitrust.

P.P.S. There’s been massive turnover among Fortune 500 companies in the post-WWII era.

———

Image credit: N i c o l a | CC BY 2.0.