Why did many European nations, most notably Greece, suffer fiscal crises about a dozen years ago?

Because the burden of government spending, which already was excessive, increased even further.

And with taxes already very onerous in those countries, much of that new spending was financed with borrowing.

Investors then realized it was very risky to finance the various spending sprees. And when they stopped buying bonds from these governments (or started demanding higher interest rates to compensate for risk), that triggered the crises.

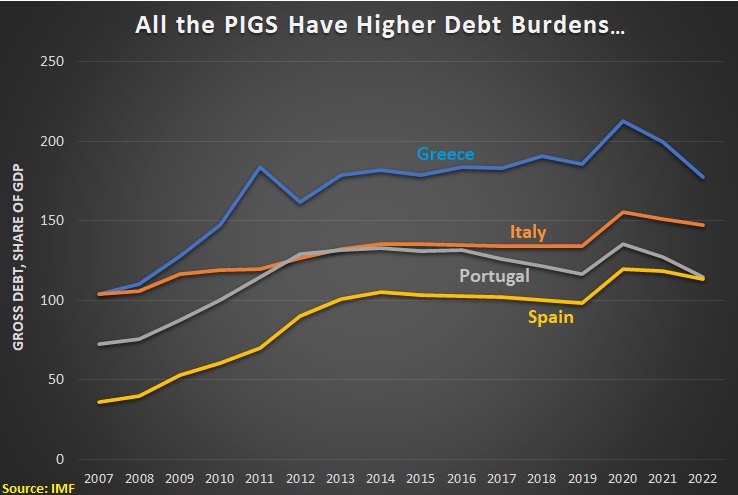

One would think that the nations most affected – Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain (the PIGS) – would have learned a lesson.

Nope.

As you can see from this IMF data, those governments did not use the post-crisis recovery as an opportunity to get debt under control. Instead, every nation has more debt today than it did when the crisis occurred.

And why do these nations have higher debt levels?

For the simple (and predictable) reason that they have not reduced the burden of government spending.

Instead, as you can see from this next chart, governments are now consuming even greater shares of national economic output. Which means a greater chance of more crises.

To make a bad situation even worse, the European Central Bank cranked up the figurative printing press starting in 2020 by massively expanding its balance sheet.

Dumping all that money into the system quite predictably caused prices to soar. And now that the ECB is belatedly trying to undo its mistake.

That puts the PIGS under more pressure, as Desmond Lachman explained for National Review.

Christine Lagarde, the president of the European Central Bank (ECB)…has to raise interest rates at a time when governments in the euro zone’s economic periphery are more indebted today than they were at the time of the 2010 euro zone sovereign-debt crisis. This more hawkish interest-rate policy, coupled with a shift to quantitative tightening, now risks triggering another round of the euro zone debt crisis. …One of the ECB’s problems in having to raise interest rates aggressively to contain inflation is that such a course risks exacerbating the cracks that are now emerging in the European banking system. …if current trends continue, then another round of euro zone sovereign-debt crisis, where investors lose faith in the government’s ability to repay its debt, could be just around the corner. …This is especially true for Italy, where until recently the ECB had been buying Italian government bonds equivalent to that government’s net borrowing needs.

By the way, Lachman seems to think the Fed should allow continued inflation in order to help bail out Italy and the other PIGS.

That would be a big mistake. The long-run damage of that approach would be much greater than the long-run damage (actually, long-run benefits) of letting Italy and the others go bankrupt.

P.S. The problem in Europe is too much government spending, not the euro currency.

P.P.S. Eurobonds will make things worse in the long run.

P.P.P.S. It is possible to reduce large debt burdens, so long as governments simply restrain spending.

P.P.P.P.S. From the archives, here’s some comedy (and more comedy) about Europe’s fiscal mess.