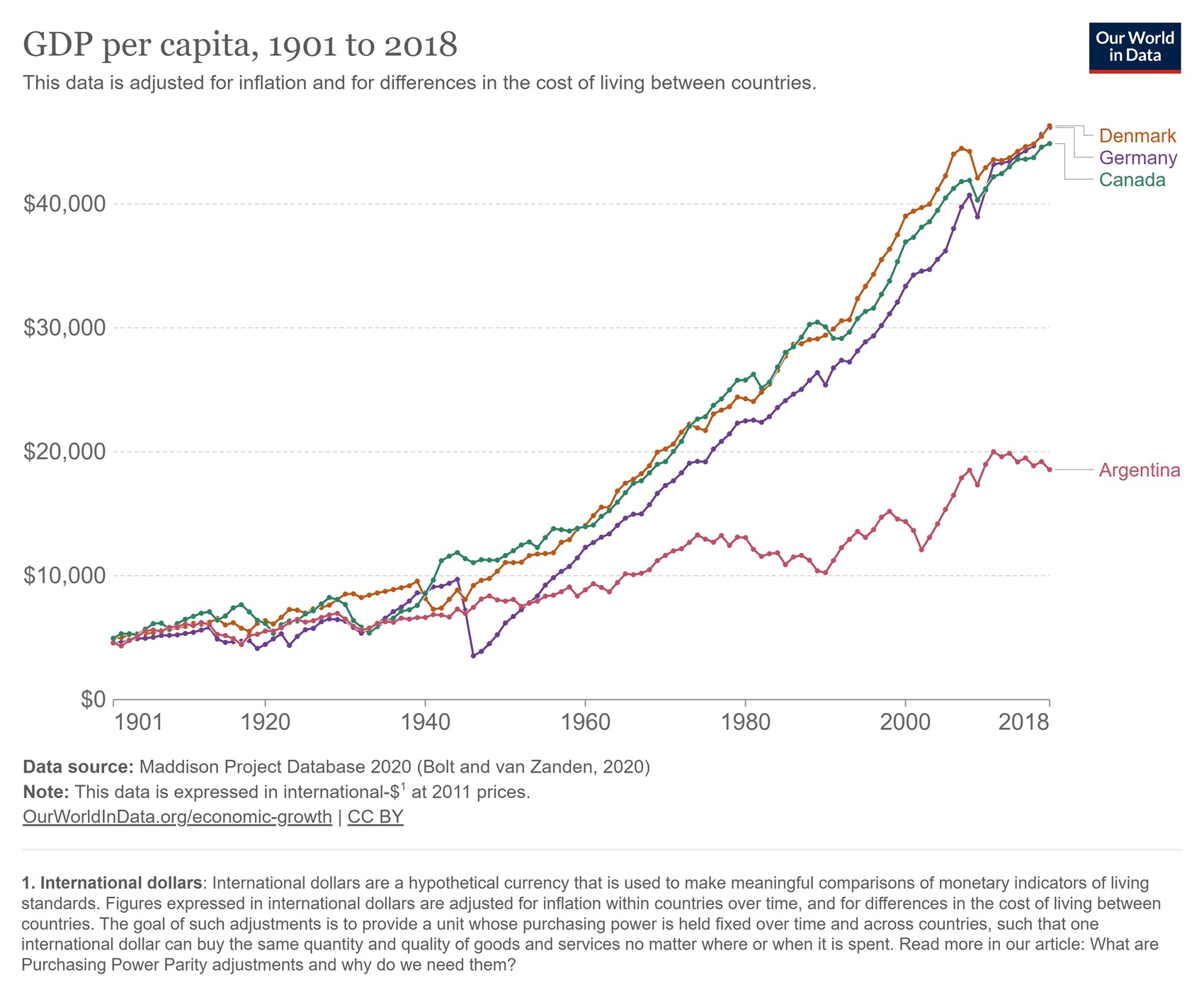

Argentina has a very interesting, but also rather tragic, economic history.

During first half of the 20th century, it was one of the world’s richest nations.

But thanks to dirigiste economic policies (known locally as Peronism) starting after World War II, Argentina has suffered a dramatic decline in relative living standards.

However, something shocking has happened. A libertarian, Javier Milei, was just elected president and he campaigned on a platform of dramatic pro-market reform.

Some people are unhappy with this outcome. For instance, Gabriel Pasquini wrote a disapproving column for the Washington Post about Milei’s victory.

His main argument is that Milei’s agenda has been tried twice in Argentina and it failed both times.

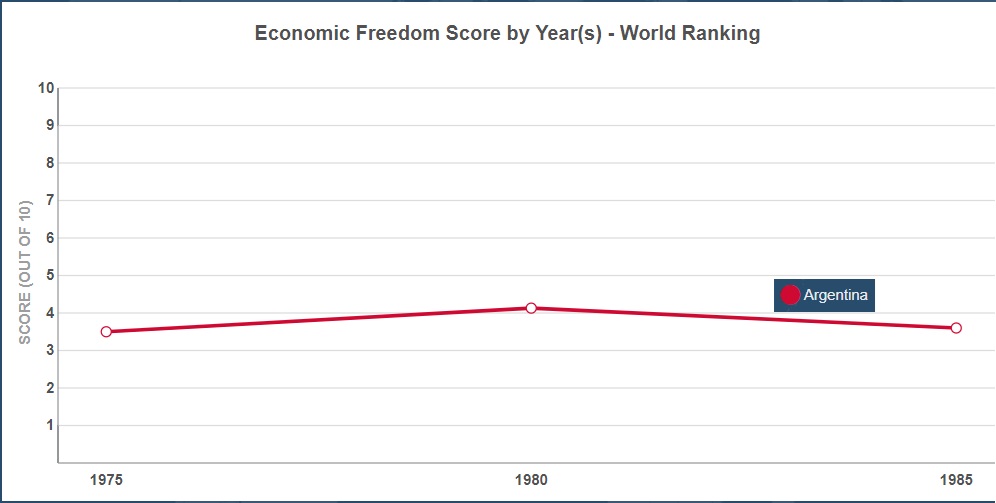

His first example is the 1976-1983 military dictatorship.

His program has been tried at least twice before, with terrible costs for Argentina. …As much as Milei likes to think otherwise, his views are not original. The last Argentine military dictatorship came to power with the slogan “Downsizing the state is making the nation bigger.” Its minister of economy, José Alfredo Martinez de Hoz, was a pre-Thatcher neoliberal who tried to deregulate the economy only for it to end up in disaster.

I’ve written a lot about the economic reforms implemented under military rule in Chile, but I confess I didn’t know anything about what happened in Argentina.

So I looked at the data from Economic Freedom of the World to see whether this was a period of economic liberalization.

Lo and behold, we find that Argentina had terrible economic policy before military rule, during military rule, and after military rule. Margaret Thatcher must be spinning in her grave at Senor Pasquini’s absurd comparison.

His second example is from the 1990s, specifically under President Carlos Menem and Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo.

In the 1990s, President Carlos Menem tried the same using a different political formula: He forced his own movement, Peronism, to embrace its historical nemesis, neoliberalism. His longest-serving minister of economy, Domingo Cavallo, deregulated the economy, while pegging the Argentine peso to the U.S. dollar to tame inflation. These policies resulted in the dramatic crisis of 2001-2002, with private savings frozen, the peso devalued and more than half the country living under the poverty line.

In this example, Pasquini gets credit for being partially correct. There actually was some economic liberalization during the 1990s.

But that’s the only thing he got right.

If we look at what he got wrong, we can start with him blaming Menem and Cavallo for the 2001-2002 crisis. Yet that happened after they were gone and more properly should be blamed on excessive government spending and other policies that made the currency peg unsustainable.

But since I’m a fan of dollarization rather than currency pegs, I have little interest in defending Argentina’s monetary policy in the 1990s (though it’s worth noting Cavallo’s approach was somewhat successful since it “brought the inflation rate down from over 1,300% in 1990 to less than 20% in 1992 and nearly to zero during the rest of the 1990s”).

Instead, I want to focus on the broader issue of whether the free market reforms in the 1990s were successful.

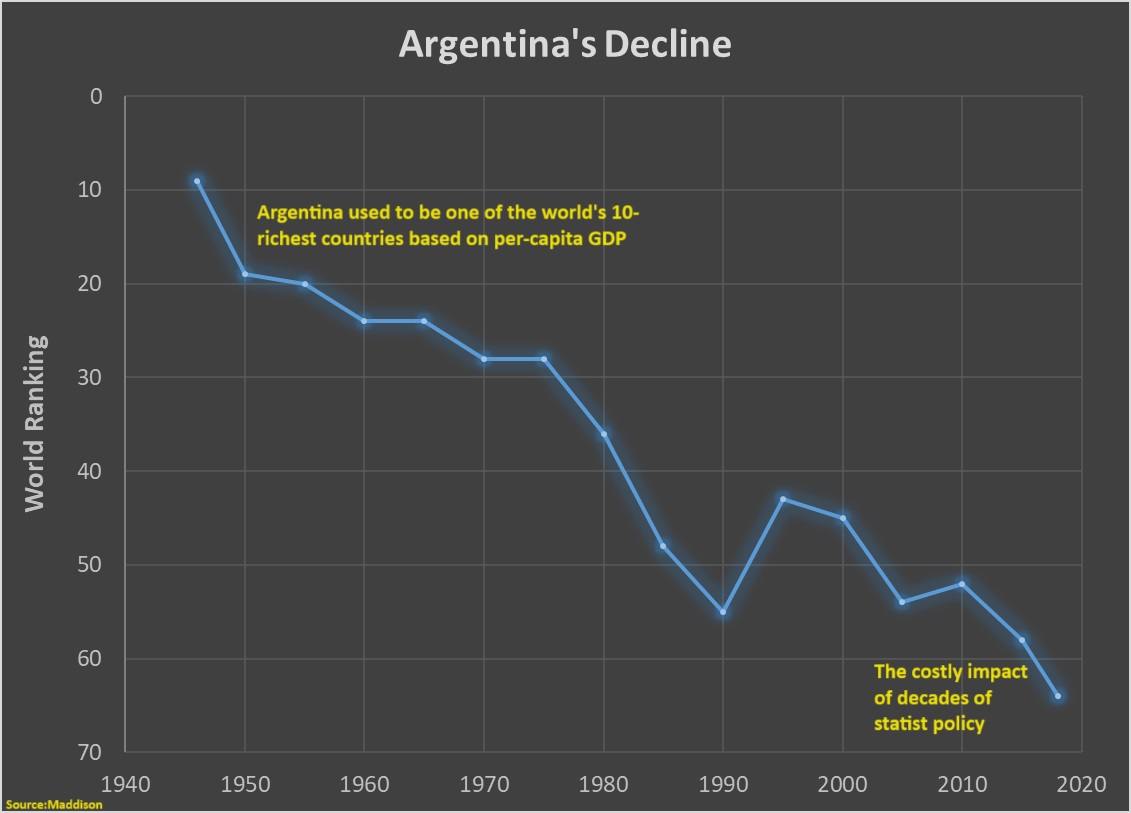

So let’s recycle a chart from an earlier column. It shows Argentina’s long-run decline, but notice that there was significant improvement in the early 1990.

The bottom line is that Argentina has been cursed with terrible policy for most of the past 70 years.

But there was a modest amount of good policy in the early 1990s, and that’s when things noticeably improved. Sadly, the few good policies of that era were then undone and lots of other bad policies have been added to the mix.

I’ve periodically asked whether Argentina can be rescued. I don’t know the answer, but I suspect Milei is the nation’s last chance to avoid societal collapse.

———

Image credit: Ilan Berkenwald | CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED.