In Part I of this series, we explained why marginal tax rates matter.

In Part II, we emphasized that low marginal tax rates are important.

Today, in Part III, let’s consider the role of payroll taxes, especially hidden payroll taxes.

To be more specific, governments often hide part of these levies (sometimes known as social insurance taxes) by ostensibly imposing them on employers.

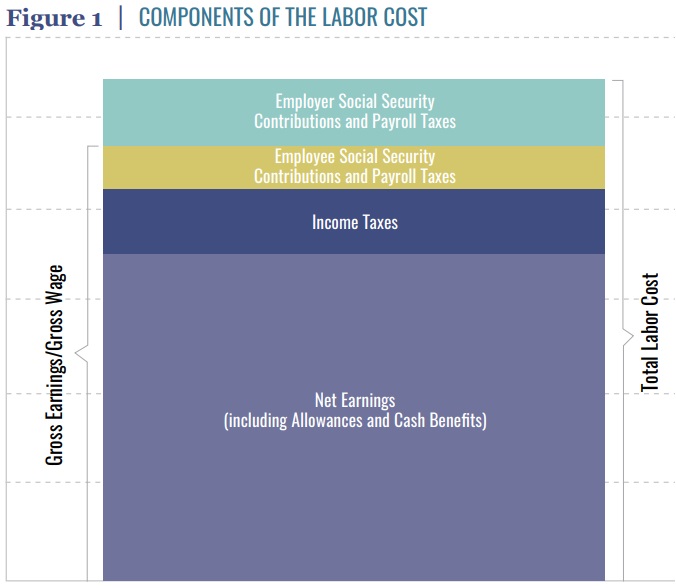

Yet labor economists universally agree that workers actually bear the burden of those taxes. Simply stated, they are part of total labor cost, as illustrated by this chart.

The chart comes from a study on marginal tax rates, which was written by Cristina Enache and published by the Archbridge Institute.

The study has all sort of data and analysis on marginal tax rates, but let’s focus on the sneaky way that politicians try to hide the full burden of payroll taxes from workers. And we’ll cite what she wrote about the U.S. system.

In the United States, the marginal tax wedge spikes are driven by local and central income taxes, payroll taxes, and tax credits such as Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC). A U.S. worker earning $47,845 costs their employer $51,812. The employer cost includes the taxes the employer has to pay on the worker’s wages. While the average tax wedge for this worker is 6 percent, the worker faces a significant marginal tax rate spike on even a small wage increase. If the employer increases compensation by just $678, this would increase the employee social security contribution by $48, employer social security contribution by $48, local government income tax by $43, and reduce central government income tax credit by only $90. The net earnings increase is $448. This U.S. single parent with two children faces a marginal tax wedge of…34 percent.

There’s a very important economic observation about the difference between the 6 percent average tax rate and the 34 percent marginal tax rate.

It’s the latter (and higher!) rate that determines the incentive to work more hours and be more productive.

But for today, let’s focus on different numbers. In the above example, the worker thinks that his or her “gross earnings/gross wages” are $47,845, but the “total labor cost” to the employer is $51,812 because of all the payroll taxes that supposedly are paid by the business.

And in Cristina’s example, she looks at what happens if the employer decides to increase total compensation by $678. The main takeaway is that the worker gets a much smaller number, just $448.

And one reason why the number is much smaller is because of the $48 of payroll tax paid by the worker and the $48 supposedly paid by the employer. But notice that the real-world impact of both taxes is to reduce the worker’s take-home pay.

In other words, there is a bigger wedge – i.e., a bigger marginal tax rate on earning more money and being more productive.

This probably seems very wonky, so I’ll conclude with a very practical observation. When you look at your pay stub, or your W-2 statement for the past year, you’ll see a section for “FICA” withholding.

That’s the payroll taxes that the government grabbed out of your paycheck. But remember that the government forced your employer to pay an equivalent amount of money on your behalf. In other words, your FICA tax burden is twice as large as you’re being told.

Simply stated, Uncle Sam is deceptively taking a slice of your income before it even gets to your gross pay.

When private businesses mislead consumers about costs, they can be sued or prosecuted. When politicians do the same thing to taxpayers, they pat themselves on the back for being clever.

P.S. Payroll taxes are not as damaging as income taxes, but that’s hardly an endorsement. Such levies still discourage work and entrepreneurship.

P.P.S. Politicians also are deceptive about dividend taxes. In an honest (and sensible) system, dividend payments would include an acknowledgement that those monies already were hit by the 21 percent corporate tax. In other words, unambiguous double taxation, but politicians hope that voters are not aware that there are two layers of tax.