If globalism means free trade and peaceful interaction among peoples, sign me up. I’m a big supporter.

But if globalism means international bureaucracies working to increase the power of governments (i.e., dirigiste forms of global governance), then I’m a big opponent.

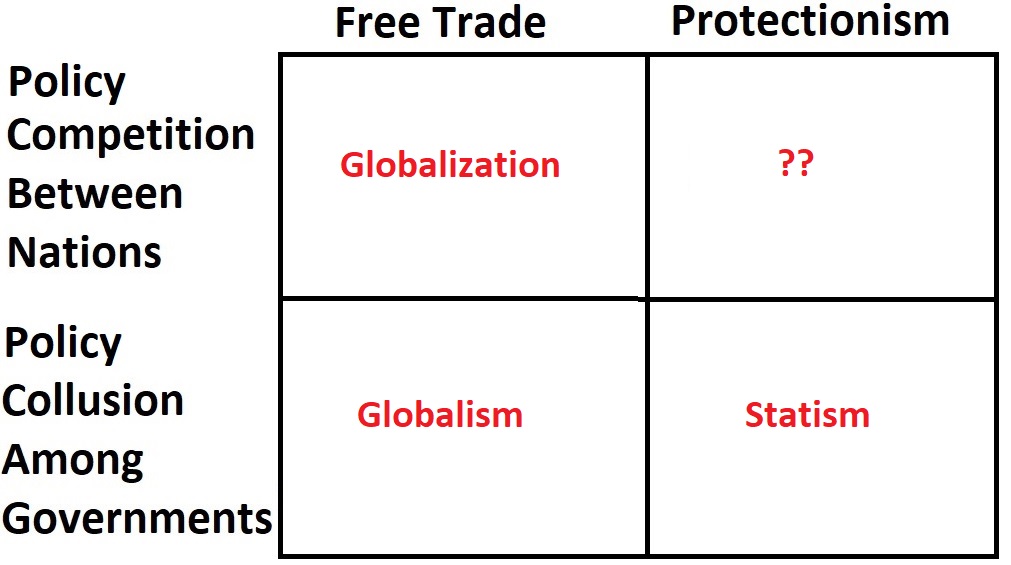

Because the word means different things to different people, I’ve explored various ways to compare and contrast “good globalism” vs “bad globalism.”

For what it’s worth, I think my 2×2 matrix needs to be revised.

One reason for an update is that “globalism” now seems more closely linked with bad policies

In an article for the US-based version of the Spectator, Roger Kimball warns against the statist version of “globalism.”

Globalism…is the enemy of freedom. Why? Because globalism systematically attacks and undermines the moral and political filiations that make genuine freedom possible. …A sterling contemporary example is the Great Reset, recently proposed by the Davos-based World Economic Forum… Here at last was an opportunity to enact a worldwide tax on wealth, a far-reaching (and deeply impoverishing) “green-energy” agenda…the WEF plan involved nothing less than the absorption of liberty by the extension of bureaucratic power. …The globalist alternative dangled before us is a version of utopia. But like The Wizard of Oz, it is all show and no substance. Or rather, the substance is an erosion of traditional sources of strength.

More specifically, the folks at the World Economic Forum are pushing a “great reset” based on “stakeholder capitalism” (which is largely repackaged “cronyism”).

Samuel Gregg of the Acton Institute opined on this issue for the Australian version of the Spectator.

The WEF is a dangerous force in global politics. …In October 2020, Schwab stated that…”Free-market fundamentalism has eroded…economic security, triggered a deregulatory race to the bottom and ruinous tax competition.” Precisely how and where ‘free-market fundamentalism’ has run amuck remains a mystery. After all, we live in a world in which most governments in developed nations routinely control 40 per cent or more of their nation’s GDP. Nor does the regulatory and welfare state’s relentless growth in, say, the European Union, Britain and America suggest that free market radicals have been in charge in Brussels, London or Washington for decades. …Ignoring these inconvenient facts, Schwab believes that the world needs a ‘Great Reset.’ …For all his invocation of the predictable woke pieties, Schwab’s core commitment is to political and economic arrangements which used to be known as corporatism. …The language of corporatism, like that of Schwab’s WEF, may be one of coordinated consultation, but the agenda is one of control. …On an economic level, corporatism discourages innovation, produces inflexible labour markets dominated by unions whose priority is maintaining the status quo, and riddle the marketplace with privileges for well-connected businesses. …anyone who believes in preserving things like liberty, sovereignty, and the decentralisation of power should be concerned.

Writing back in 2020 for the Wall Street Journal, Richard Shinder opined about the dirigiste agenda of modern-day globalists compared to the good version of globalism that existed in the 19th century.

Globalism touts the supremacy of supranational bodies and accords—the United Nations, the Paris climate agreement and the like. …many aspects of today’s globalism—or at least its promotion of market economies, capital mobility, and mostly free trade—aren’t in conflict with nationalism. In one sense of the word, the greatest “globalist” age in history was the period before World War I. Trade among western European countries increased to 10% of the region’s GDP in 1900 from 1% in 1830. Supply chains extended across the globe, and capital and labor flowed freely across borders. The “long” 19th century…was also a time of industrialization, enormous poverty reduction, wealth creation and global economic integration. This unabashed age of nation-states wasn’t all roses, but it was one of free markets, free trade and unrestricted capital flows. …this period demonstrates that globalism need not be unaccountable nor collectivist. …international institutions…shouldn’t impinge on national sovereignty. Sovereign nations consenting to play by an agreed set of rules, or banding together in service of a common objective, differs radically from unaccountable transnational elites engineering outcomes, often without scrutiny. …Nationalism as a response to a collectivist and unaccountable globalism—whether in dealing with a “climate crisis,” “inequality,” or something else—need not be nativist or protectionist. …the nation-state remains the most successful vehicle for advancing liberty, economic advancement and individual achievement in the history of the world.

For a differing perspective, Dalibor Rohac of the American Enterprise Institute made the case for globalism in a column for the Washington Examiner.

Humankind has become vastly more prosperous with extensive international cooperation. Since 1950, the world’s population has roughly tripled; over the same time, real output has increased by more than a factor of 10. In Botswana and South Korea, real per capita incomes have grown 38 and 30 times, respectively. Global prosperity is a direct outcome of economic globalization. Compared to automation, trade accounts for a tiny fraction of total job losses in the U.S. Meanwhile, cheaper consumer products imported from overseas have been among the most effective anti-poverty “policies” in the Western world. …This would not be possible without…the open trading environment created by successive rounds of multilateral trade liberalization under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and, later, the World Trade Organization.

I fully agree about the global benefits of free trade, and the World Trade Organization has played a helpful role.

Moreover, Dalibor also mentions other international agreements and entities that are unobjectionable.

Or even desirable. After all, does anyone oppose the parts of the “rules-based postwar order” that facilitate things such as cross-border air travel, international shipping, and global telecommunications?

But the helpful work of those bodies doesn’t change the fact that major international bureaucracies engage in activities that are counterproductive. A “rules-based order” is only good, after all, if it advancing good rules.

- Is it helpful for the OECD to push for rules hindering tax competition?

- Is it helpful for the IMF to push for rules exacerbating moral hazard?

- Is it helpful for the EU to push for rules requiring tax harmonization?

- Is it helpful for the UN to push for rules undermining civil liberties?’

- Is it helpful for the Basel folks to push for rules increasing systemic risk?

The bottom line is that governments should be competing against each other, not conspiring with each other.

Which leads me to a revised version of my 2×2 matrix (the upper-right quadrant is empty because protectionist nations, by definition, don’t want jurisdictional competition).

To summarize, yes to globalization, no to global governance.

P.S. If the choice is nation states vs. global governance, the answer is obvious.

P.P.S. While I prefer nation states over global governance, I’m not happy that the European Union is morphing from an international bureaucracy into a nation state.