As far as I’m concerned, the huge reductions in global poverty in recent decades are the only evidence we need about the benefits of economic growth.

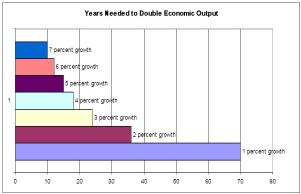

This chart I shared in 2014 shows that output doubles much faster when annual economic growth goes from low levels (1 percent or 2 percent) to high levels (4 percent or above).

I call this the miracle of compounding.

Needless to say, I also argue that nations experience high levels of growth with the right policies and the right perspective.

But not everyone thinks policy makers should focus on getting more economic growth. Some of them (the “Okunites“) are willing to sacrifice some prosperity to achieve more equality, while others dislike growth because of the environment.

In a column for the Foundation for Economic Education, Saul Zimet points out that the people who downplay growth are no friends of the poor.

Economic degrowth is terrible for almost everyone, but it endangers the poor most of all. Therefore, it is remarkable that the problems with degrowth are appreciated least by those who claim to be most focused on the interests of the lower classes. …Socialist political commentator Ian Kochinski, who goes by the pseudonym Vaush, has said that, “One of the unfortunate truths of being a socialist is you have to accept that your nation will not get to enjoy the skyrocket GDP growth that capitalist nations get to enjoy. There is going to be a sacrifice of some economic efficiency, to the benefit of hopefully making life better for everybody.” Some growth critics go even further than to question the importance of growth as a policy target. …Naomi Klein calls economic growth “reckless and dirty” and advocates a policy of “radical and immediate degrowth”.

Zimet explains how this agenda is bad news for those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder.

… those brought out of extreme poverty, which have mostly been in places like China and India, were largely not helped by massive social programs but by a growing global market for their labor. …George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen explains…that, “In the medium to long term, even small changes in growth rates have significant consequences for living standards. An economy that grows at one percent doubles its average income approximately every 70 years, whereas an economy that grows at three percent doubles its average income about every 23 years—which, over time, makes a big difference in people’s lives.”

Professor Glenn Hubbard, an economist at Columbia University, makes the case for growth in an article for National Review.

A slightly higher rate of economic growth, sustained over time, can make the difference between a big increase in living standards and relative stagnation. …Nobel Prize–winning economist Robert Lucas famously observed that once economists think of long-term growth, it is hard to think of anything else. A pro-growth policy agenda is a good idea because growth is a good idea. …Higher output can come from growth in inputs such as labor and capital, but what determines their growth? Today’s economists highlight population growth and society’s willingness to work, save, and invest. Still more important is growth in productivity, or the efficiency with which inputs are used to produce goods and services. …McCloskey, an economic historian, has similarly identified the continuous, large-scale, voluntary, and unfocused search for betterment as the source of new ideas that can produce economic growth. She sees this “innovism” as primarily a cultural force, preferring the term to the more familiar “capitalism,” and connects innovism to economic liberalism.

Prof. Hubbard notes that economic growth requires creative destruction, but also acknowledges that this process causes pain.

And that politicians often respond to pain with bad ideas.

Forces that propel growth invariably leave a wake of economic disruption for people in many places… A serious discussion of pro-growth policy must account for that disruption. …growth is messy. It can push some individuals, firms, and even industries off well-worn and comfortable paths. …A gentle industrial policy devised by social scientists who are worried about jobs is not the answer. It results in state tinkering for special interests…it risks a vicious cycle: A little bit of tinkering becomes a lot of tinkering.

Instead of industrial policy, Hubbard suggests a couple of policies, most notably a better system of community colleges.

That would be a good outcome, of course.

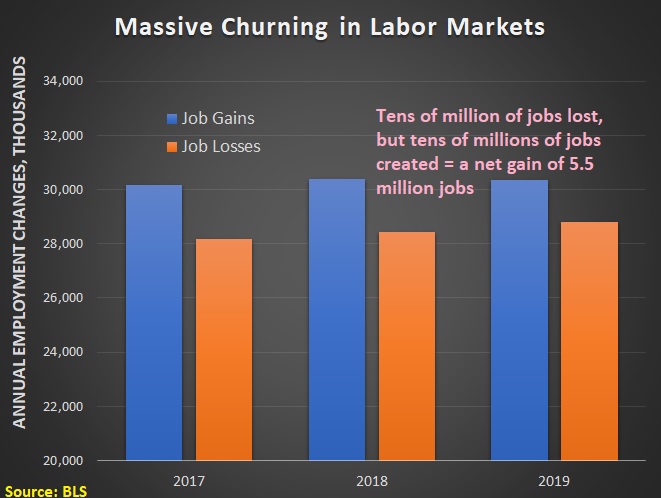

From a big-picture perspective, though, I think net job creation is the best way to mitigate the political downsides of creative destruction.

It is not good news if 15 million jobs are destroyed in a particular year (especially for the people and communities that are directly harmed).

But if more than 15 million jobs are created the same year, that surely makes it easier for people to find new opportunities.