I wrote last year that today’s Americans are much richer than their parents and grandparents (and the gap becomes even more enormous when comparing with earlier generations).

But the data I cited almost surely understate the improvement in living standards.

That’s the core takeaway of a new book, Superabundance, authored by Marian Tupy of the Cato Institute and Professor Gabe Pooley from Brigham Young University in Hawaii.

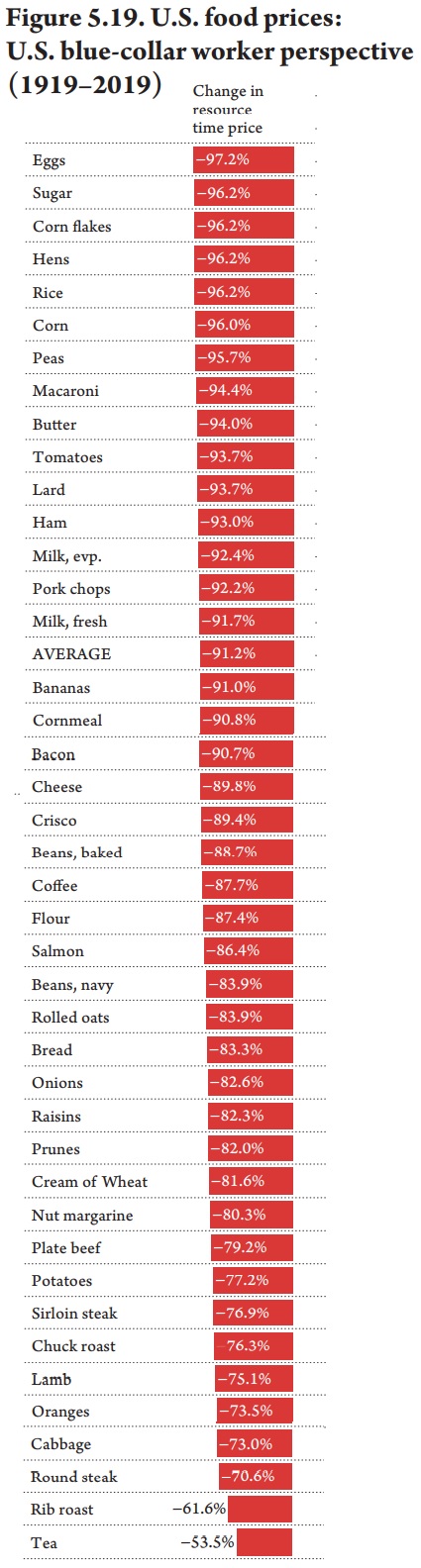

The book is filled with an immense amount of data and analysis, all of which shows that life is getting better. For purposes of today’s column, we’re going to highlight some fascinating numbers about the “time price” of various goods.

The authors explain that the “time price (TP) denotes the amount of time that a person needs to work in order to earn enough money to be able to buy something.”

In simple terms, this calculation shows how many hours we had to work to buy something in the past compared to how many hours we have to work to buy the same thing today.

For some items, such as food, there’s enough long-run data to see how the “time price” has changed over the past 100 years. The bottom line is that there’s been an amazing increase in our purchasing power.

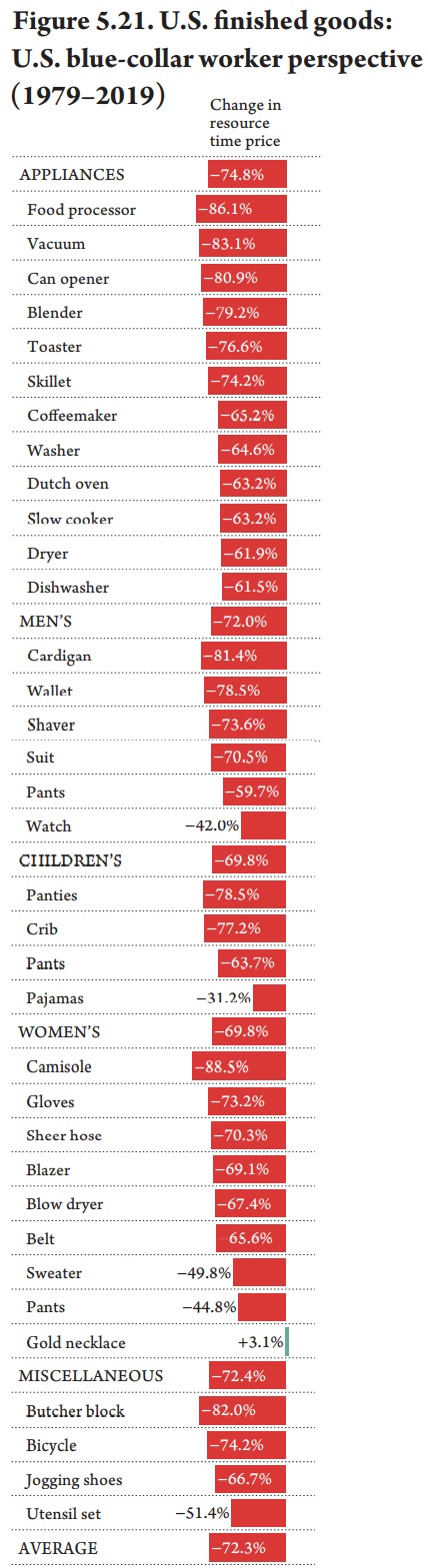

What about non-food items?

Well, many of the things we buy today did not exist 100 years ago, so let’s look at four decades of data to see what’s happened to purchasing power in the United States.

As you can see, we can obtain almost everything by working far fewer hours.

For people who like hard data, the book is like an encyclopedia.

You can also get numbers for a “personal resource abundance multiplier” to see how much and how fast living standards have increased.

For example, a 97.2% decline in the price of eggs relative to the wages of a blue-collar worker between 1919 and 2019 means that:

- a) The same length of work that got the blue-collar worker one egg in 1919 got him 36 eggs in 2019

- b) That worker’s “egg abundance” rose by 3,500%

- c) That worker’s egg abundance increased by 3.65% per year

- d) The egg abundance doubled every 19.34 years.

For those who want to augment numbers with analysis, Chapter 8 describes what happened.

Even after Homo sapiens embraced agriculture some 12,000 years ago, progress was painfully slow. People lacked basic medicines and died relatively young. They had no painkillers, and people with ailments spent much of their lives in agonizing pain. Entire families lived in bug-infested dwellings that offered neither comfort nor privacy. They worked in the fields from sun- rise to sunset, yet hunger and famines were commonplace. …In a remarkable and sudden transition, though, standards of living sky- rocketed over the last two centuries, first in Western Europe and North Amer- ica, and then in other parts of the world. The consequences of that increase in economic growth were monumental. For the first time in human history, our species overcame Malthusian limits on production and consumption. The Age of Innovation ushered in unprecedented and even unimaginable improvements in wealth, life expectancy, nutrition, health, clothing, working conditions, and education. Extreme poverty, infant and maternal mortalities, and child labor declined.

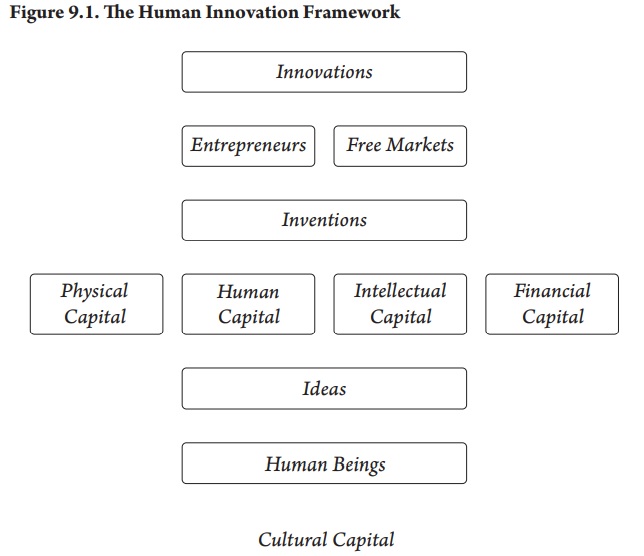

Chapter 9 describes why it happened.

Individuals, who lack equal legal rights, and face onerous regulatory burdens, confiscatory taxation, or insecure property rights, will be disincentivized from turning their ideas into inventions and innovations. Conversely, people who function under conditions of legal equality, sensible regulation, moderate taxation, and secure property rights will apply their talents to their benefit and, ultimately, to that of society. …Free markets serve one other beneficial role in human society: they build trust and cooperation. Competition, as everyone knows, is an essential part of a capitalist economy. It drives businesses to innovate and to provide consumers with less costly and better products. If businesses fail to innovate, they go under. …Capitalism is also one of the most cooperative of human endeavors, though. Goods and services are traded among strangers and across vast distances, guided to a great degree by the price mechanism and by the reputation of the trading parties. …In the short run, competition produces winners and losers (although over the long run it is very difficult to find anyone in a market society who does not daily enjoy substantial gains or “wins” from market competition).

I’ll also add this flowchart from Chapter 9 to show the importance of free markets and entrepreneurship.

I’ll add one final point, which is that we don’t need perfect policy to get more prosperity.

The economy simply needs “breathing room,” which will exist so long as politicians don’t get too crazy about over-taxing, over-spending, and over-regulating.

After all, even small differences in annual economic growth compound into big changes in living standards.

———

Image credit: fujikanakama0 | Pixabay License.