Ideally, the federal government should be limited to the functions specified by the Founders in Article 1, Section 8, of the Constitution.

If we are to have any hope of getting back to that system, it may require two practical steps.

- If Washington is operating a program, the first step may be to replace it with block grants and let state and local governments decide how to spend the money.

- If Washington is providing block grants, the second step may be to phase out that funding and let state and local governments figure out if they want to pick up the cost.

To elaborate, programs that are both funded by Washington and operated by Washington not only suffer from waste (common to all government activities), but also produce the inefficiency and stagnation common to a one-size-fits-all approach.

This is why welfare reform under Bill Clinton was a good idea.

Taxpayers saved some money because the block grant was capped. But the best outcome was that states then could use their flexibility to innovate and find approaches that actually helped poor people by encouraging employment and reducing dependency.

In an ideal world, however, there should not be block grants. State and local governments should decide not only how to operate welfare programs, but also how to finance them.

To understand the problems associated with block grants, let’s look at a new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Authored by Jeffrey Clemens, Philip G. Hoxie & Stan Veuger, it finds that pandemic grants were grotesquely inefficient.

We use an instrumental-variables estimator reliant on variation in congressional representation to analyze the effects of federal aid to state and local governments across all four major pieces of COVID-19 response legislation. Through September 2021, we estimate that the federal government allocated $855,000 for each state or local government job-year preserved. Our baseline confidence interval allows us to rule out estimates of less than $433,000. Our estimates of effects on aggregate income and output are centered on zero and imply modest if any spillover effects onto the broader economy.

Needless to say, it’s absurd to spend $433,000-$855,000 to save a job that pays an average of $100,000. Or less.

On net, that’s going to reduce total employment when you count the private-sector jobs that are foregone because politicians are diverting so much money from the economy’s productive sector.

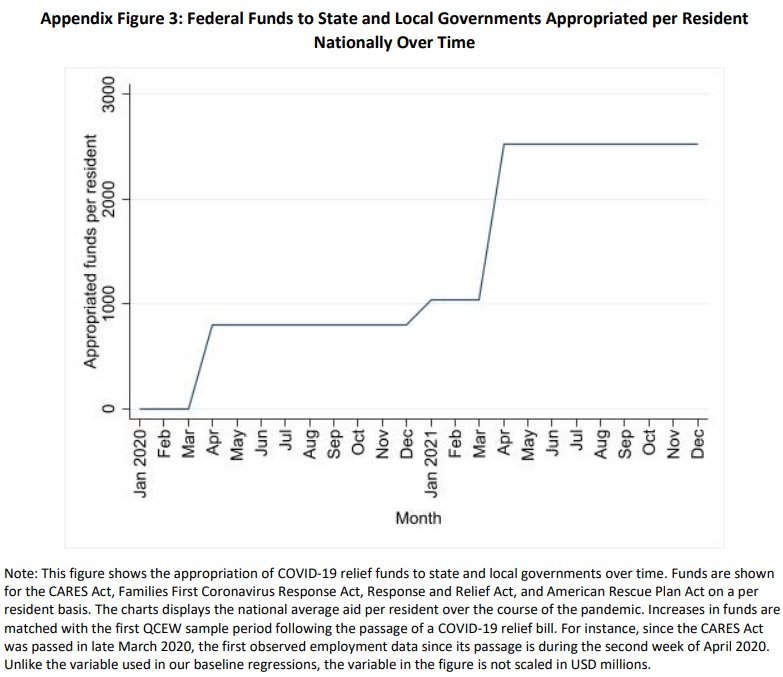

And if you want to know how much money was diverted specifically for state and local governments, Figure 3 shows both Trump’s pandemic boondoggle in 2020 and Biden’s pandemic boondoggle in 2021.

In a column for the Foundation for Economic Education, Peter Jacobsen discusses the new study.

The authors find that federal aid to state and local governments to save jobs was incredibly ineffective. In fact, this program was even more inefficient than the notoriously inefficient Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). …The PPP was estimated to have cost somewhere from $169,000 to $258,000 per job each year. This program to save state and local government jobs cost in the range of $433,000 to $855,000 per job each year. This is as much as 5x more waste! …So how did the government spend more than $800,000 per job to save jobs which normally pay five figures? …a business engaging in an ineffective and wasteful policy like this would make a loss on each worker and go out of business. …government is particularly prone to generating these wasteful jobs. …Without a mechanism like profit and loss to evaluate the value of alternative options, we are left with a policy which spends nearly a million dollars to preserve a single job with a salary less than one tenth of that.

I’ll conclude with the should-be-obvious observation that politicians don’t actually care about net job creation. They care about buying votes with other people’s money.

So the state and local bureaucrats who directly benefited (by keeping their over-compensated jobs) presumably will remember and reward the politicians who supported for the boondoggles.

P.S. The rest of us also should care – and oppose spendthrift politicians, but most of us don’t pay enough attention to recognize the “unseen.”