I was excited about the possibility of pro-growth tax policy during the short-lived reign of Liz Truss as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

However, I’m now pessimistic about the nation’s outlook. Truss was forced to resign and big-government Tories (akin to big-government Republicans) are back in charge.

As part of my “European Fiscal Policy Week,” let’s take a closer look at what happened and analyze the pernicious role of the Bank of England (the BoE is their central bank, akin to the Federal Reserve in the U.S.).

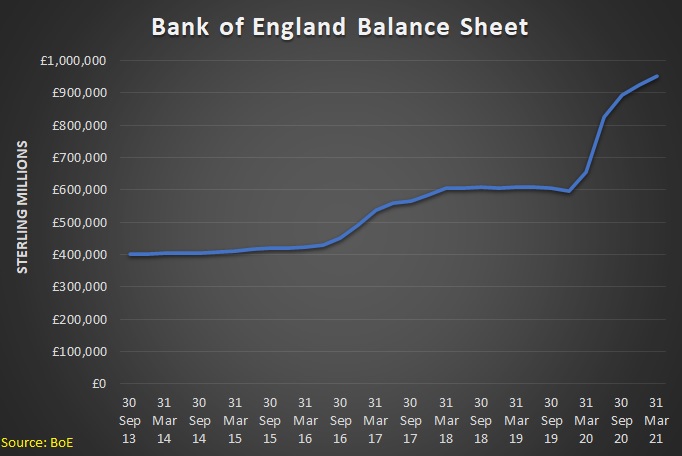

Let’s start with a reminder that the Bank of England panicked during the pandemic and (like the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank) engaged in dramatic monetary easing.

That was understandable in the spring of 2020, perhaps, but it should have been obvious by the late summer that the world was not coming to an end.

Yet the BoE continued with its easy-money policy. The balance sheet kept expanding all of 2020, even after vaccines became available.

And, as shown by the graph, the easy-money approach continued into early 2021 (and the most-recent figures show the BoE continued its inflationary policy into mid-2021).

Needless to say, all of that bad monetary policy led to bad results. Not only 10 percent annual inflation, but also a financial system made fragile by artificially low interest rates and excess liquidity.

So how does any of this relate to fiscal policy?

As the Wall Street Journal explained in an editorial on October 10, the BoE’s bad monetary policy produced instability in financial markets and senior bureaucrats at the Bank cleverly shifted the blame to then-Prime Minster Truss’ tax plan.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey is trying to stabilize pension funds, which are caught on the shoals of questionable hedging strategies as the high water of loose monetary policy recedes. …The BOE is supposed to be tightening policy to fight inflation at 40-year highs and claims these emergency bond purchases aren’t at odds with its plans to let £80 billion of assets run off its balance sheet over the next year. But BOE officials now seem confused about what they’re doing. …No wonder markets doubt the BOE’s resolve on future interest-rate increases. Undeterred, the bank is resorting to the familiar bureaucratic imperative for self-preservation. Mr. Cunliffe’s letter is at pains to blame Mr. Kwarteng’s fiscal plan for market ructions. His colleagues Jonathan Haskel and Dave Ramsden —all three are on the BOE’s policy-setting committee—have picked up the theme in speeches that blame market turbulence on a “U.K.-specific component.” This is code for Ms. Truss’s agenda. …Mr. Bailey doesn’t help his credibility or the bank’s independence by politicizing the institution.

In a column for Bloomberg, Narayana Kocherlakota also points a finger at the BoE.

And what’s remarkable is that Kocherlakota is the former head of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve and central bankers normally don’t criticize each other.

Markets didn’t oust Truss, the Bank of England did — through poor financial regulation and highly subjective crisis management. …The common wisdom is that financial markets “punished” Truss’s government for its fiscal profligacy. But the chastisement was far from universal. Over the three days starting Sept. 23, when the Truss government announced its mini-budget, the pound fell by 2.2% relative to the euro, and the FTSE 100 stock index declined by 2.2% — notable movements, but hardly enough to bring a government to its knees. The big change came in the price of 30-year UK government bonds, also known as gilts, which experienced a shocking 23% drop. Most of this decline had nothing to do with rational investors revising their beliefs about the UK’s long-run prospects. Rather, it stemmed from financial regulators’ failure to limit leverage in UK pension funds. …The Bank of England, as the entity responsible for overseeing the financial system, bears at least part of the blame for this catastrophe. …the Truss government…was thwarted not by markets, but by a hole in financial regulation — a hole that the Bank of England proved strangely unwilling to plug.

Last but not least, an October 18 editorial by the Wall Street Journal provides additional information.

When the history of Britain’s recent Trussonomics fiasco is written, make sure Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey gets the chapter he deserves. …The BOE has been late and slow fighting inflation… Mr. Bailey’s actions in the past month have also politicized the central bank…in a loquacious statement that coyly suggested the fiscal plan would be inflationary—something Mr. Kwarteng would have disputed. …Meanwhile, members of the BOE’s policy-setting committee fanned out to imply markets might be right to worry about the tax cuts. If this was part of a strategy to influence fiscal policy, it worked. …Mr. Bailey may have been taking revenge against Ms. Truss, who had criticized the BOE for its slow response to inflation as she ran to be the Conservative Party leader this summer. Her proposed response was to consider revisiting the central bank’s legal mandate. The BOE’s behavior the past month has proven her right beyond what she imagined.

So what are the implications of the BoE’s responsibility-dodging actions?

- First, we should learn a lesson about the importance of good monetary policy. None of this mess would have happened if the BoE had not created financial instability with an inflationary approach.

- Second, we should realize that there are downsides to central bank independence. Historically, being insulated from politics has been viewed as the prudent approach since politicians can’t try to artificially goose an economy during election years. But Bailey’s unethical behavior shows that there is also a big downside.

Sadly, all of this analysis does not change the fact that tax cuts are now off the table in the United Kingdom. Indeed, the new Prime Minister and his Chancellor of the Exchequer have signaled that they will continue Boris Johnson’s pro-tax agenda.

That’s very bad news for the United Kingdom.

P.S. There used to be at least one sensible central banker in the United Kingdom.

P.P.S. But since sensible central bankers are a rare breed, maybe the best approach is to get government out of the business of money.

———

Image credit: David Iliff | CC BY-SA 3.0.