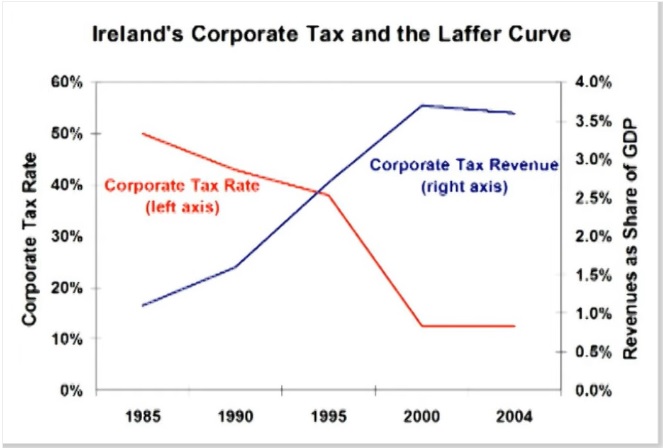

In the case of business taxation, the most visually powerful evidence for the Laffer Curve is what happened to corporate tax revenue in Ireland after the corporate tax rate was slashed from 50 percent to 12.5 percent.

Tax revenue increased dramatically. Not just in nominal terms. Not just in inflation-adjusted terms.

Corporate receipts actually climbed as a share of GDP.

And this was during the decades when economic output was rapidly expanding.

In other words, the Irish government got a much bigger slice of a much bigger pie after tax rates were dramatically lowered.

Now let’s look at some evidence from a new study. Three professors from the University of Utah (Jeffrey Coles, Elena Patel, and Nather Seegert), and a Treasury Department economist (Matthew Smith) estimated what happens to taxable income for U.S. companies when there is a change in the corporate tax rate.

In response to a 10% increase in the expected marginal tax rate, private U.S. firms decrease taxable income by 9.1%, which indicates a discernibly more elastic response than prevailing estimates. This response reflects a decrease in taxable income of 3.0% arising from real economic responses to a firm’s scale of operations and 6.1% arising from accounting transactions via (for example) revenue and expense timing. Responsiveness to the corporate tax rate is more elastic if a firm uses cash (9.9%) rather than accrual accounting (7.4%), if the firm is small (9.9%) rather than large (8.6%), and if the firm discounts future cash flows at a lower rate.

The paper is filled with equation, graphs, and jargon, but the above excerpt tells us everything we need to know.

When tax rates go up, taxable income goes down (both because there is less economic activity and because companies have more incentive to manipulate the tax code).

Thus confirming what I wrote back in 2016 about taxable income being the key variable.

By the way, this does not mean that lower tax rates lead to more revenue. Or that higher tax rate produce less revenue.

Such big swings only happen in rare circumstances.

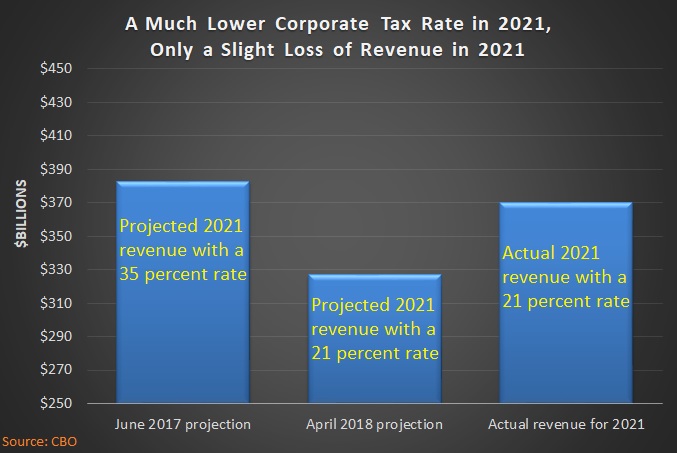

But it does mean that politicians will not grab as much money as they hope when they increase tax rates. And that they won’t lose as much revenue as they fear when they lower tax rates (and we saw that most recently with the 2017 tax reform).

I’ll close by noting that this is additional evidence for why we should be thankful that Biden’s proposal for higher corporate tax rates was not enacted.

P.S. The chart at the beginning of this column may be the most visually powerful evidence for the corporate Laffer Curve. The most empirically powerful evidence, however, comes from very unlikely sources – the pro-tax IMF and the pro-tax OECD.

———

Image credit: geralt | Pixabay License.