As part of my (reality-based) opposition to a value-added tax, I testified to the Ways & Means Committee back in 2011.

My primary argument against the VAT is that it would enable a bigger burden of government spending.

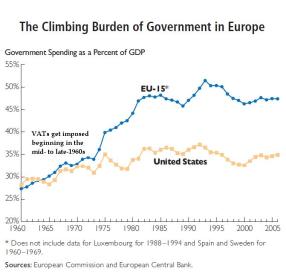

I frequently share this chart, for instance, that shows that the nations in Western Europe were quite similar to the United States back in the 1960s, with government budgets that consumed about 30 percent of economic output.

That was before they enacted VATs.

But once European politicians got that new source of revenue, the spending burden diverged, with the welfare state becoming a much larger burden in Western Europe than in the United States.

In other words, the VAT was a money machine for big government.

That argument is just as accurate today as it was back in 2011.

For today’s column, however, I want to focus on what I said in the last minute of my testimony (beginning about 4:00).

I pointed out that VAT supporters are wrong when they claim that adoption of this new tax would enable reductions in the income tax.

And if you peruse my written testimony, you’ll see that I included several charts showing how tax burdens changed between 1965 and 2008. In every case, I showed that European politicians actually increased the burden of income taxes after they enacted their VATs.

Is that still true?

Of course.

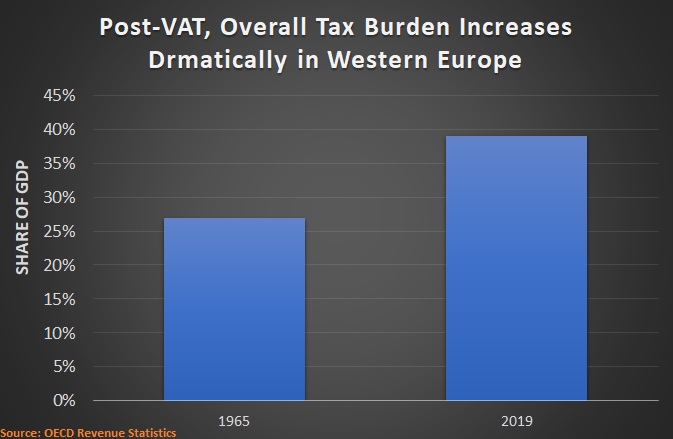

Here’s an updated version of the chart showing that the overall tax burden dramatically increased after VATs were imposed.

In the United States, by contrast, the overall tax burden only increased during this time period from 23.6 percent of GDP to 25 percent of GDP.

Still bad news, but nowhere near as bad as Western Europe, where the overall tax burden jumped by more than 13 percentage points.

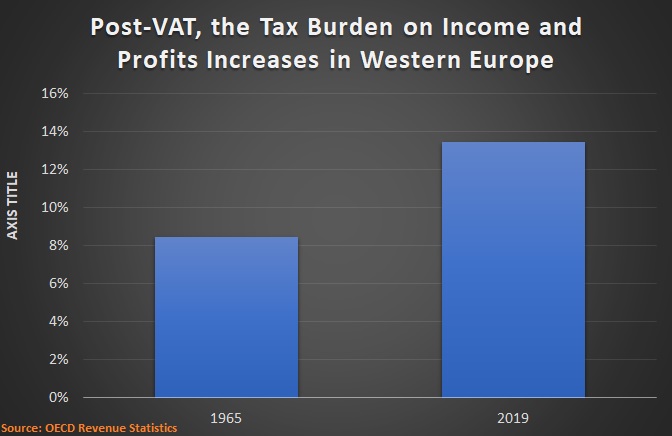

Now let’s peruse the updated version of the chart showing what happened to taxes on income and profits.

As you can see, European governments definitely did not use VAT revenues to lower other taxes.

In the United States, by contrast, the tax burden on income and profits only increased during this time period from 11.3 percent of GDP to 11.6 percent of GDP.

Still bad news, but nowhere near as bad as Western Europe, where the tax burden on income and profits jumped by nearly 5 percentage points.

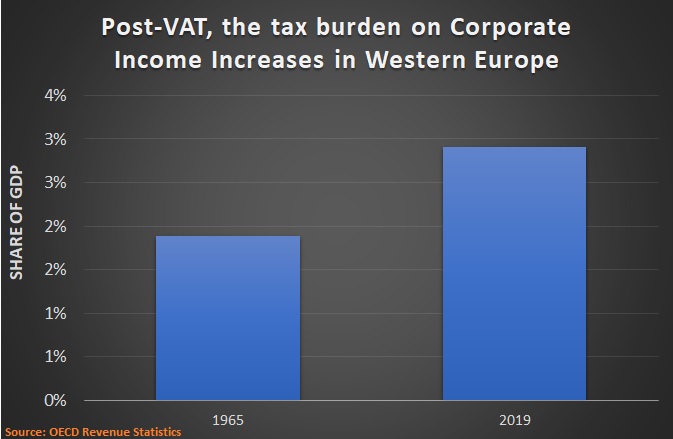

Now let’s peruse the updated version of the chart showing what happened to taxes on corporations (this chart is especially important because there are very naive people in the business community who think that they can avoid higher taxes on their companies if they surrender to a VAT).

As you can see, governments in Europe have been grabbing more money from corporations since VATs were imposed.

In the United States, by contrast, the tax burden on corporations actually decreased during this time period from 3.9 percent of GDP to 1.3 percent of GDP.

By every possible measure, the value-added tax is a big mistake (as even the IMF inadvertently shows).

Unless, of course, politicians first get rid of the income tax – including repealing the 16th Amendment and replacing it with an ironclad prohibition against any future income tax.

But that’s about as likely as me playing the outfield for the New York Yankees in this year’s World Series.

P.S. I mentioned at the very end of my testimony that we did not have clear evidence from other nations that subsequently adopted VATs. In the case of Japan, we now do have data showing how the VAT is financing bigger government.

P.P.S. Some VAT advocates actually claim the levy is good for growth. That’s a nonsensical claim. VATs drive a wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption. What they really mean to say is that VATs don’t do as much damage, on a per-dollar-raised basis, as conventional income taxes (with punitive rates and double taxation).

P.P.P.S. You can enjoy some good anti-VAT cartoons here, here, and here.