Earlier this year, I pointed out that President Biden should not be blamed for rising prices.

There has been inflation, of course, but the Federal Reserve deserves the blame. More specifically, America’s central bank responded to the coronavirus pandemic by dumping a lot of money into the economy beginning in early 2020.

Nearly a year before Biden took office.

The Federal Reserve is not the only central bank to make this mistake.

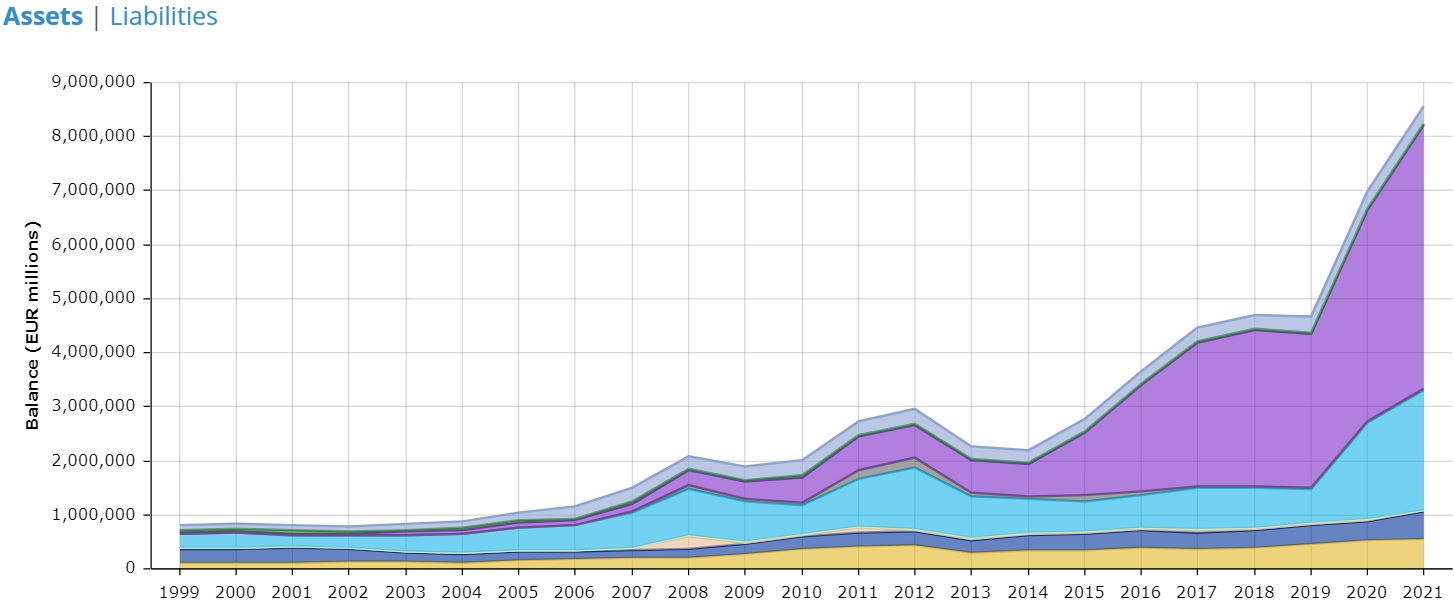

Here’s the balance sheet for the Eurosystem (the European Central Bank and the various national central banks that are in charge of the euro currency). As you can see, there’s also been a dramatic increase in liquidity on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Why should American readers care about what’s happening with the euro?

In part, this is simply a lesson about the downsides of bad monetary policy. For years, I’ve been explaining that politicians like easy-money policies because they create “sugar highs” for an economy.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that false booms almost always are followed by real busts.

But this is more than a lesson about monetary policy. What’s happened with the euro may have created the conditions for another European fiscal crisis (for background on Europe’s previous fiscal crisis, click here, here, and here).

In an article for Project Syndicate, Willem Buiter warns that the European Central Bank sacrificed sensible monetary policy by buying up the debt of profligate governments.

…major central banks have engaged in aggressive low-interest-rate and asset-purchase policies to support their governments’ expansionary fiscal policies, even though they knew such policies were likely to run counter to their price-stability mandates and were not necessary to preserve financial stability. The “fiscal capture” interpretation is particularly convincing for the ECB, which must deal with several sovereigns that are facing debt-sustainability issues. Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain are all fiscally fragile. And France, Belgium, and Cyprus could also face sovereign-funding problems when the next cyclical downturn hits.

Mr. Buiter shares some sobering data.

All told, the Eurosystem’s holdings of public-sector securities under the PEPP at the end of March 2022 amounted to more than €1.6 trillion ($1.7 trillion), or 13.4% of 2021 eurozone GDP, and cumulative net purchases of Greek sovereign debt under the PEPP were €38.5 billion (21.1% of Greece’s 2021 GDP). For Portugal, Italy, and Spain, the corresponding GDP shares of net PEPP purchases were 16.4%, 16%, and 15.7%, respectively. The Eurosystem’s Public Sector Purchase Program (PSPP) also made net purchases of investment-grade sovereign debt. From November 2019 until the end of March 2022, these totaled €503.6 billion, or 4.1% of eurozone GDP. In total, the Eurosystem bought more than 120% of net eurozone sovereign debt issuances in 2020 and 2021.

Other experts also fear Europe’s central bank has created more risk.

Two weeks ago, Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute expressed concern that Italy had become dependent on the ECB.

…the European Central Bank (ECB) is signaling that soon it will be turning off its monetary policy spigot to fight the inflation beast. Over the past two years, that spigot has flooded the European economy with around $4 trillion in liquidity through an unprecedented pace of government bond buying. The end to ECB money printing could come as a particular shock to the Italian economy, which has grown accustomed to having the ECB scoop up all of its government’s debt issuance as part of its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program. …the country’s economy has stalled, its budget deficit has ballooned, and its public debt has skyrocketed to 150 percent of GDP. …Italy has had the dubious distinction of being a country whose per capita income has actually declined over the past 20 years. …All of this is of considerable importance to the world economic outlook. In 2010, the Greek sovereign debt crisis shook world financial markets. Now that the global economy is already slowing, the last thing that it needs is a sovereign debt crisis in Italy, a country whose economy is some 10 times the size of Greece’s.

Mr. Lachman also warned about this in April.

Over the past two years, the ECB’s bond-buying programs have kept countries in the eurozone’s periphery, including most notably Italy, afloat. In particular, under its €1.85 trillion ($2 trillion) pandemic emergency purchase program, the ECB has bought most of these countries’ government-debt issuance. That has saved them from having to face the test of the markets.

And he said the same thing in March.

The ECB engaged in a large-scale bond-buying program over the past two years…, as did the U.S. Federal Reserve. The size of the ECB’s balance sheet increased by a staggering four trillion euros (equivalent to $4.4 billion), including €1.85 trillion under its Pandemic Emergency Purchasing Program. …The ECB’s massive bond buying activity has been successful in keeping countries in the eurozone’s periphery afloat despite the marked deterioration in their public finances in the wake of the pandemic.

Let’s conclude with several observations.

- First, many European countries are at risk because politicians, year after year, have spent too much money (Italy is just the tip of the iceberg).

- Second, the ECB has enabled much of that spending by buying a lot of the government debt issued by Europe’s profligate nations.

- Third, there’s now a bubble thanks to the combination of bad fiscal policy by national governments and bad monetary policy by the ECB.

- Fourth, some economic misery is unavoidable, but the damage can be limited if governments impose Swiss-style spending caps.

- Fifth, the political elite in Europe do not want spending restraint and instead prefer very bad policies such as “debt mutualization.”

So if politicians won’t adopt good policies and their bad policies won’t work, what’s going to happen?

At some point, national governments will probably default.

That’s an unpleasant outcome, but at least it will stop the bleeding.

Unlike bailouts and easy money, which exacerbate the underlying problems.

P.S. For what it is worth, I do not think a common currency is necessarily a bad idea. That being said, I wonder if the euro can survive Europe’s awful politicians.

P.P.S. While I think Mr. Buiter’s article in Project Syndicate was very reasonable, I’ve had good reason to criticize some of his past analysis.