As a libertarian, I view defense spending with the same jaundiced eye that I apply to domestic spending.

- I’ve pointed out that the U.S. represents a big share of global military outlays.

- I’ve pointed out that sequestration wasn’t a threat to military preparedness.

- I’ve pointed out that legacy defense commitments may be senseless nowadays.

And here’s a more-updated view of how much the United States spends on the military compared to other nations.

Call me crazy, but this chart indicates that the United States is probably spending too much on the Pentagon.

For what it’s worth, it’s possible that America’s lead is exaggerated because China and Russia get more bang for their buck on their military spending, but it’s also worth noting that the rest of the nations on the list are largely allied with the United States.

Farhad Manjoo of the New York Times writes there is too much spending on defense. But he undermines the credibility of his position with a deceptive comparison of domestic and defense outlays.

…the nearly three-quarters of a trillion dollars that we are spending this year on a military that has become the epitome of governmental dysfunction, self-dealing and overspending. …does it make any sense to keep spending so many hundreds of billions on the Pentagon? …The Pentagon has never passed an audit… Congress is projected to spend about $8.5 trillion for the military over the next decade — about half a trillion more than is budgeted for all nonmilitary discretionary programs combined… You don’t have to be a pacifist to wonder if this imbalance between military and nonmilitary spending makes sense.

The problem with what he wrote is that he compares defense spending only to the portion of domestic spending that is considered “discretionary.”

And this leaves out all the entitlement programs – which are the biggest and fastest growing part of the federal budget.

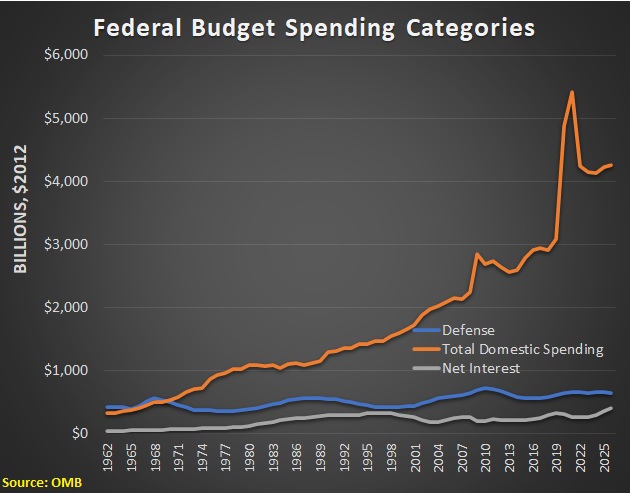

So I went to section 8 of the Historical Tables of the Budget and put together this chart, based on inflation-adjusted dollars, showing total domestic spending (huge and growing), total defense spending (relatively flat), and interest payments on the national debt (relatively flat).

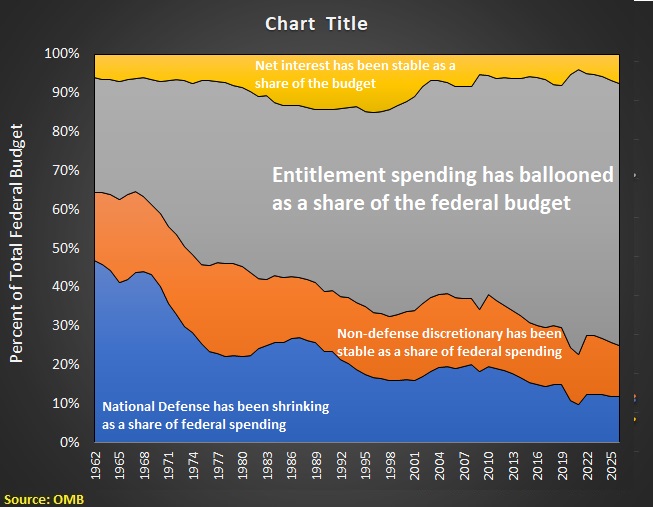

Next, let’s look at the data showing what share of the budget goes to different types of spending.

For this chart, I’ve separated domestic entitlements and domestic discretionary.

Once again, the obvious and unambiguous takeaway is that domestic spending is the problem in general, with entitlements being the problem in particular.

Now that we know that entitlement programs are America’s main fiscal challenge, let’s close with a couple of reminders that we also should take a knife to the Pentagon’s budget.

This headline for a story in USA Today.

This heading from a story in Stars & Stripes.

This headline from a story in the New York Times.

And if you want other examples of military waste, click here, here, and here.

But don’t forget that the big savings from defense budget can be achieved by reevaluating whether it makes sense to maintain alliances against enemies that no longer exist, along with reconsidering the wisdom of nation building.

———

Image credit: David B. Gleason | CC BY-SA 2.0.