I realize few readers are interested in small, faraway countries. But I periodically write about nations such as Jordan, Cyprus, Latvia, Vanuatu, Panama, and Pakistan because they offer important lessons – mostly negative, but sometimes positive – about fiscal policy.

Today, let’s see what we can learn from Barbados.

That island nation in the Caribbean wound up in fiscal trouble a few years ago and Abrahm Lustgarten of the New York Times wrote a lengthy article last week about that experience.

Here’s the situation as of 2018.

Barbados was out of money. It was so broke that it was taking out new loans just to pay the interest on the old ones, even as its infrastructure was coming undone. Soon the nation would have no choice but to declare itself insolvent, instigating a battle with the dozens of banks and creditors that held its $8 billion in debt and triggering austerity measures that would spiral the island into further poverty. …Mottley, the first woman to lead Barbados, had been working…to develop a plan that would restructure the country’s soaring debts in a way that would free up money to invest in Barbados’s economy.

While the preceding excerpts are mostly to illustrate what was happening, I can’t resist two editorial comments.

- First, the right kind of austerity produces growth rather than poverty.

- Second, government spending rarely acts as productive investment.

Now let’s get back to the story.

Prime Minister Mottley’s plan involved going to the International Monetary Fund, then headed by Christine Lagarde, for a bailout.

Mottley knew that banks and investors would work with her only if Barbados were participating in a formal I.M.F. program… Mottley wanted Lagarde to endorse an economic program that would still allow her to raise salaries of civil servants, build schools and improve piping and wiring for water and power. …No one was sure how Lagarde would respond. Would she trust Mottley to spend on Barbados first? …the director’s surprising reply: She was extremely supportive of what Mottley was proposing.

Needless to say, I don’t like bailouts. And a bailout that enables more government spending seems especially foolish.

But I like to check the numbers before making sweeping pronouncements.

And while I am very skeptical of IMF bailouts, I like that the international bureaucracy has an extensive database with economic and fiscal numbers. Including fiscal data for Barbados going back to 1994.

So let’s see whether Barbados somehow was being hurt by inadequate levels of government spending.

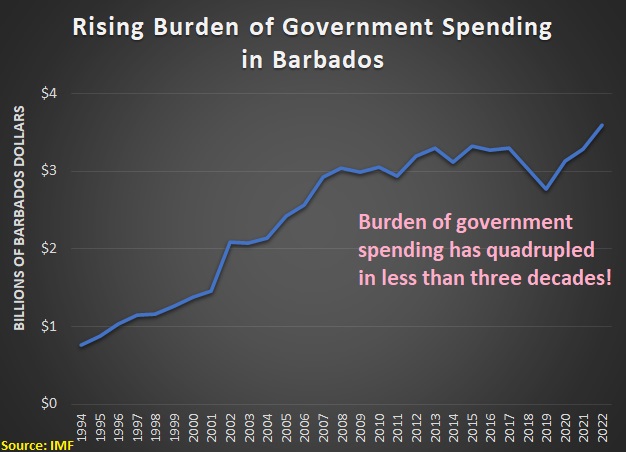

But it turns out that total government spending today is more than four times greater than it was in 1994.

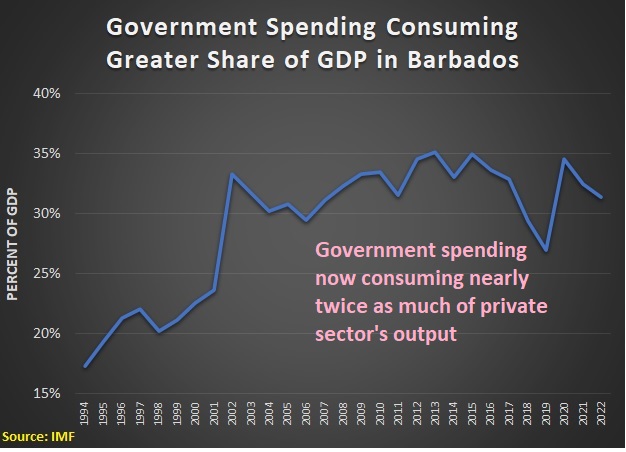

And if we look at government spending as a share of gross domestic product, we can see that government has nearly doubled in size.

To be fair to Ms. Mottley, the politicians in office from 1994-2008 were the most profligate.

But none of that changes the fact that government is far bigger today than it was in the recent past. So the notion that Barbados needs a bigger government budget is nonsense.

Sadly, the reporter did not bother to share any of these numbers. Indeed, in a story that ran more than 10,000 words, there were only 50 words that even hinted at the real problem.

…a mixture of poor management and corruption had eroded the country’s economy. …the country had developed a “dysfunctional” fiscal culture in which government agencies and departments took loans and negotiated deals without consulting the central bank, accumulating sprawling debt… The country’s response was to print more money and borrow more.

I’ll close by observing that Barbados never would have gotten into trouble if it had a Swiss-style spending cap. If government spending had been allowed to grow only 3 percent each year starting in 1994, Barbados would be enjoyed a huge budget surplus today.

P.S. Ironically, economists at the IMF have written in favor of spending caps on multiple occasions. Too bad the political hacks in charge of the bureaucracy don’t pay attention to that research.

———

Image credit: scaturchio | CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.