One of the (many) unfortunate tendencies of politicians is that they focus on the short run (i.e., their upcoming reelection battles).

Why is this unfortunate? Because there are some policy changes that may be costly in the short run, but they are nonetheless very worthwhile because they generate big long-run benefits.

- Shifting to a system of personal retirement accounts means trillions of dollars of near-term “transition costs” in order to protect current retirees and older workers, but reform will solve the program’s long-term $40 trillion-plus unfunded liability.

- Messy fights over the debt limit create (almost certainly exaggerated) concerns about potential default, but that potential cost would be trivial compared to the long-run benefits of figuring out how to limit the growing burden of federal spending.

- When bad monetary policy causes a financial bubble or housing bubble, shifting to good monetary policy presumably will lead to short-run pain as markets adjust, but that’s far better than producing a 2008-style crisis by letting the bubble(s) expand further.

I offer the above examples because similar short-run and long-run tradeoffs exist when looking at what happens when the International Monetary Fund provides bailouts for profligate governments.

The Economist has an article that perfectly illustrates the IMF’s pernicious role.

The year was 1958. …Argentina turned to the fund for its first “standby arrangement”, a line of credit accompanied by a plan to stabilise the economy. …Sixty years later, in June 2018, Argentina was back for its 21st arrangement: a $50bn loan, later increased to $57bn, backed by the government’s promises to cut the budget deficit and strengthen the central bank in the hope of quelling inflation and stabilising the peso. The loan was the largest in the imf’s history. …Despite its size, the rescue failed to save Argentina from default and despair. …Foreign capital kept retreating, the peso kept falling and inflation kept rising. The evaluation speculates that the size of the imf’s loan may even have been “self-defeating”, eroding confidence rather than inspiring it.

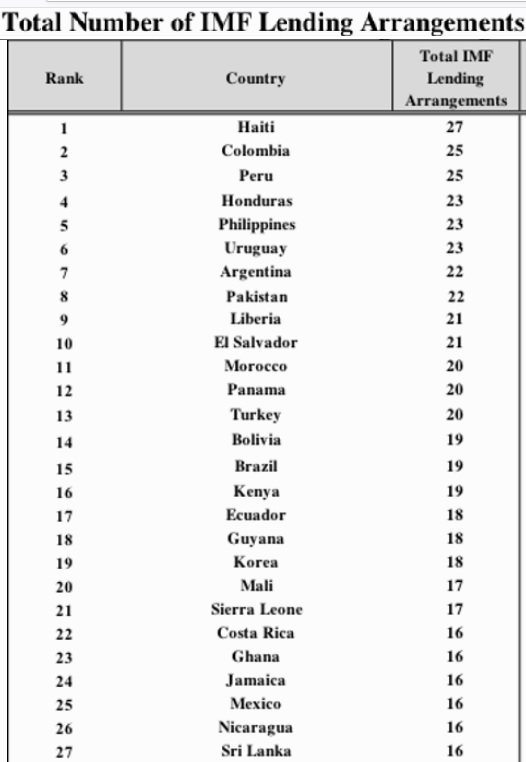

Just in case you missed it, the article mentions that Argentina has received 21 different bailouts since 1958, which works out to be one bailout every three years (Professor Steve Hanke counts 22 bailouts, for what it’s worth).

In probably every case, IMF bureaucrats presumably thought a bailout was a way of minimizing economic pain (and they probably thought the same thing for dozens of bailouts provided to Haiti, Colombia, Peru, Honduras, Philippines, etc).

But what actually has happened is that politicians – in Argentina and elsewhere – have learned that it’s okay to pursue bad policy because there’s always another bailout.

In other words, IMF policy is a glaring example of “moral hazard.” By shielding politicians from the consequences of bad policy, the bureaucracy is actually encouraging those politicians to engage in additional bad policy.

To be blunt, the IMF is the arsonist rather than the firefighter.

The article in the Economist included this observation.

Conservative critics think the fund has been seduced by its dance partner, wasting public money in a futile battle.

My right-leaning friends are correct, but their criticisms are too mild.

It’s not just that the IMF is wasting money. It’s dampening growth by pushing policies that misallocate capital.

It’s not just that the IMF is engaging in a futile battle. It’s making problems far worse by enabling ever-more government.

Here’s what should have happened to Argentina in 1958 (and what should have happened in 2018, and what should happen when there’s pressure for yet another bailout).

- The investors who buy Argentinian government bonds should learn that lending to dodgy governments is a risky practice.

- The politicians in Argentina who spend excessively should learn that there’s a tipping point when they can no longer borrow.

- The interest groups in Argentina should learn that parasites also suffer when they kill their host animal by being too greedy.

- The voters in Argentina should learn that there are serious adverse consequences when you elect “Peronist” politicians.

Sadly, none of these lessons get learned so long as the IMF is standing by to provide never-ending bailouts.

So instead of some short-run pain, which is then offset by better long-run policy, we get bailouts that mask short-run pain and encourage more long-run damage.

The moral of the story? Shut down the IMF.

The sad reality? The IMF is getting more power.

P.S. To add injury to injury, the IMF usually insists that governments raise taxes in exchange for getting bailed out.

P.P.S. To be fair, the IMF recommends tax increases even in the years when bailouts aren’t needed, so at least the bureaucrats have a consistent (albeit nutty) message.

———

Image credit: eliasbuty | Pixabay License.