America’s fiscal future is very grim, largely because of an ever-expanding burden of entitlement spending.

To see the magnitude of the problem, let’s peruse the Budget and Economic Outlook, which was released yesterday by the Congressional Budget Office has some.

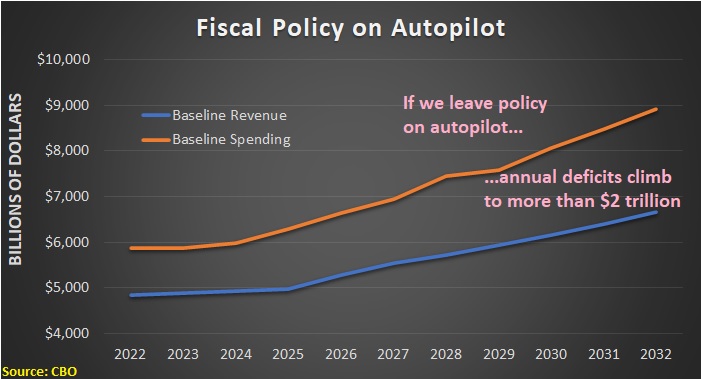

Most people are focusing on how deficits are going to climb from $1 trillion to $2 trillion-plus over the next 10 years.

That’s not good news, but we should be far more worried about the fact that the burden of government spending is growing faster than the private economy. As a result, government will be consuming an ever-larger share of national output.

The budget wonks who (mistakenly) focus on red ink say the problem is so serious that we need higher taxes.

They look at this chart, which is based on CBO’s baseline forecast (what will happen if taxes and spending are left on autopilot), and assert we have no choice but to raise taxes.

They point out that the annual deficit in 2032 will be almost $2.3 trillion and that it’s impossible cut spending by that much.

Needless to say, it would be a near-impossible political undertaking to cut $2.3 trillion in one year (though it would fulfill libertarian fantasies).

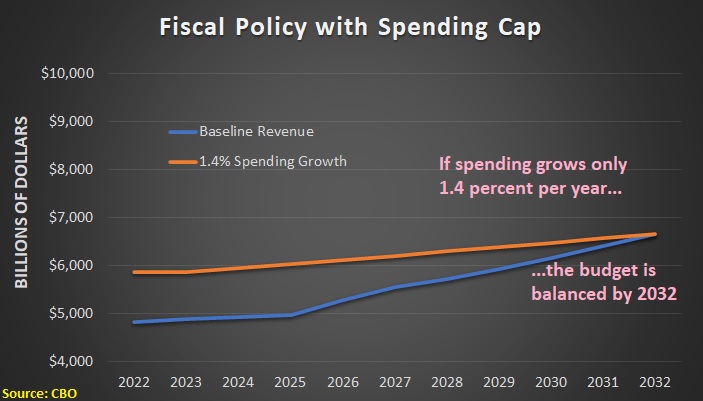

But what if, instead of kicking the can down the road, policymakers imposed some sort of overall spending cap to avoid a giant deficit in 10 year.

This second chart displays that scenario. I took CBO’s baseline (autopilot) numbers and assumed that spending could only increase by 1.4 percent annually starting in 2024.

As you can see, that modest bit of fiscal discipline completely eliminates the project $2.3 trillion annual deficit in 2032.

In other words, there is no need for any tax increase.

Especially since politicians almost certainly would respond to the expectation of additional revenue by increasing spending above the baseline (as would happen with Joe Biden’s so-called Build Back Better scheme).

I’ll close by noting that there’s no need to fixate on whether the budget is balanced by 2032. What matters is trend lines.

It’s not good for government to grow faster than the private economy in the long run. And it’s not good for deficits and debt to climb as a share of economic output in the long run.

Both of those outcomes can be avoided if we have some sort of spending cap so that outlays grow slower than the private sector.

The stricter the cap, the quicker the progress.

- I prefer actual cuts (a requirement to reduce nominal spending each year).

- I would be happy with a hard freeze (like we had for a few years after the Tea Party revolt).

- As noted above, a 1.4 percent spending cap balances the budget by 2032.

- But we would make progress, albeit slow progress, even if the spending cap allowed the budget to grow by 2.0 percent of 2.5 percent per year.

P.S. I start the spending cap in 2024 because spending is not projected to grow by very much between 2022 and 2023. That’s not because today’s politicians are being responsible, however. It’s simply a result of one-time pandemic emergency spending coming to an end. But since that one-time spending has a big impact on short-run numbers, I delayed the spending cap for one year.

P.P.S. The blue revenue line has a kink in 2025 because the baseline forecast assumes that many of the Trump tax cuts expire that year. If those tax cuts are extended or made permanent, revenues would be about $400 billion lower in 2032. As such, balancing the budget by that year would require a spending cap that allows annual outlays to increase by less than 0.9 percent per year.

P.P.P.S. President Biden is bragging that the deficit is falling this year, but that’s only because the one-time pandemic spending is coming to an end.

P.P.P.P.S. A spending cap is a simple solution, but it would not be an easy solution. In the long-run, it would require genuine entitlement reform.

———

Image credit: Pictures of Money | CC BY 2.0.