The title of this column is an exaggeration. What we’re really going to do today is explain the main things you need to know about government debt.

We’ll start with this video from Kite and Key Media, which correctly observes that entitlement programs are the main cause of red ink.

I like that the video pointed out how tax-the-rich schemes wouldn’t work, though it would have been nice if they added some information on how genuine entitlement reform could solve the problem (as you can see here and here, I’ve also nit-picked other debt-themed videos).

Which is why I humbly think this is the best video ever produced on the topic.

As you can see, I’m not an anti-debt fanatic. It was perfectly okay, for instance, to incur debt to win World War II.

But I’m very skeptical of running up the nation’s credit card for routine pork and fake stimulus.

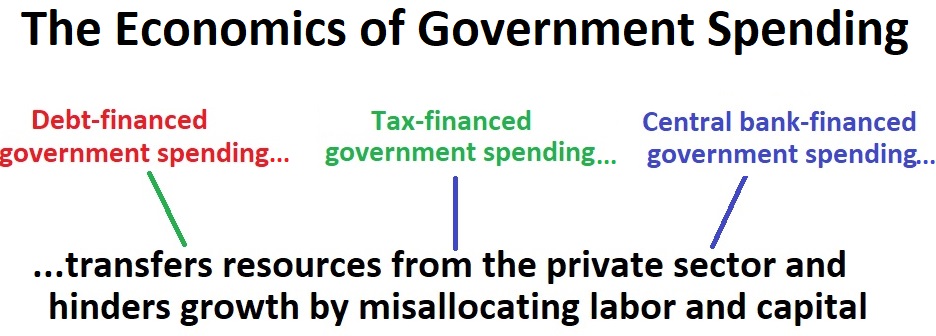

But my main message, which I’ve shared over and over again, is that deficits and debt are merely a symptom. The underlying disease is excessive government spending.

And that spending hurts our economy whether it is financed by taxing or borrowing (or, heaven forbid, by printing money).

Now let’s look at some recent articles on the topic.

We’ll start with Eric Boehm’s column for Reason, which explains how red ink has exploded in recent years.

America’s national debt exceeded $10 trillion for the first time ever in October 2008. By mid-September 2017 the national debt had doubled to $20 trillion. …data released by the U.S. Treasury confirmed that the national debt reached a new milestone: $30 trillion. …Entitlements like Social Security and Medicare are in dire fiscal straits and will become even more costly as the average American gets older. Even without another unexpected crisis, deficits will exceed $1 trillion annually, which means the debt will continue growing, both in real terms and as a percentage of the economy. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal government will add another $12.2 trillion to the debt by 2031.

As already stated, I think the real problem is the spending and the debt is the symptom.

But it is possible, of course, that debt rises so high that investors (the people who buy government bonds) begin to lose faith that they will get repaid.

At that point, governments have to pay higher interest rates to compensate for perceived risk of default, which exacerbates the fiscal burden.

And if there’s not a credible plan to fix the problem, a country can go into a downward spiral. In other words, a debt crisis.

This is what happened to Greece. And I think it’s just a matter of time before it happens to Italy.

Heck, many European nations are vulnerable to a debt crisis. As are many developing countries. And don’t forget Japan.

Could the United States also be hit by a debt crisis? Will we reach a “tipping point” that leads to the aforementioned loss of faith?

That’s one of the possibilities mentioned in the New York Times column by Peter Coy.

It’s hard to know how much to worry about the federal debt of the United States. …Either the United States can continue to run big deficits and skate along with no harm done or it’s at risk of losing investors’ confidence and having to pay higher interest rates on its debt, which would suppress economic growth. …the huge increase in federal debt incurred during and after the past two recessions — those of 2007-09 and 2020 — has used up a lot of the “fiscal space” the United States once had. In other words, the federal government is closer to the tipping point where big increases in debt finally start to become a real problem. …any given amount of debt becomes easier to sustain as long as the growth rate of the economy (and thus the growth rate of tax revenue) is higher than the interest rate on the debt. In that scenario, interest payments gradually shrink relative to tax revenue. …but it doesn’t explain how much more the debt can grow. …Past a certain point, there’s a double whammy of more dollars of debt plus higher interest costs on each dollar. …sovereign debt crises tend to be self-fulfilling prophecies: Investors get nervous about a government’s ability to pay, so they demand higher interest rates, which raise borrowing costs and produce the bad outcome they feared. It’s a dynamic that Argentines are familiar with — and that Americans had better hope they never experience.

For what it’s worth, I think other major nations will suffer fiscal crisis before the problem becomes acute in the United States.

I realize this will make me sound uncharacteristically optimistic, but I’m keeping my fingers crossed that this will finally lead politicians to adopt a spending cap so we don’t become Argentina.

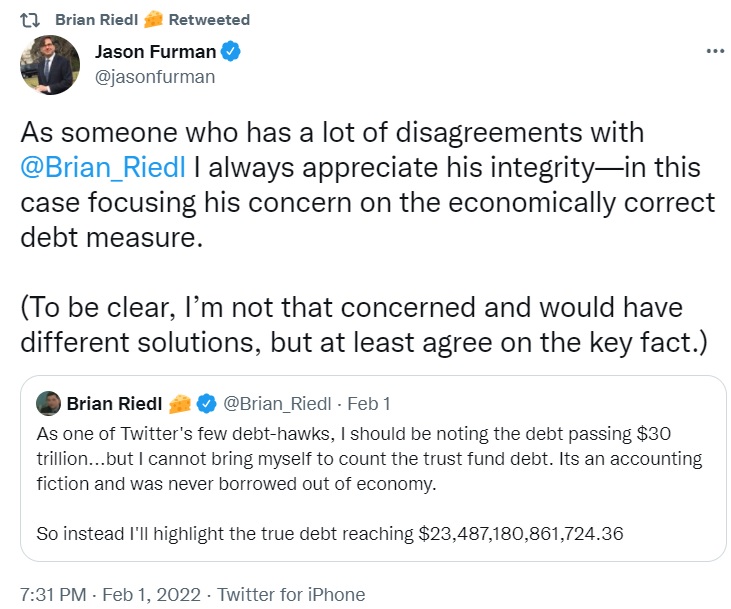

P.S. The Wall Street Journal recently editorialized on the issue of government debt and made a very important point about the difference between the $30 trillion “gross debt” and the “debt held by the public,” which is about $6 trillion lower.

…the debt really isn’t $30 trillion. About $6 trillion of that is debt the government owes to itself in Social Security and other IOUs. …The debt held by the public is some $24 trillion, which is bad enough.

As I’ve noted when writing about Social Security, the IOUs in government trust funds are not real.

They’re just bookkeeping entries, as even Bill Clinton’s budget freely admitted.

Indeed, if you want to know whether some is both honest and knowledgeable about budget matters, ask them which measure of the national debt really matters.

As you can see from this exchange of tweets, competent and careful budget people (regardless of whether they favor big government or small government) focus on “debt held by the public,” which is the term for the money government actually borrows from credit markets.

If you want to know the difference between the various types of government debt – including “unfunded liabilities” – watch this video.

P.P.S. This column explains how and when debt matters. If you’re interested in how to reduce the debt, there’s very good evidence that spending restraint is the only effective approach. Even in cases where debt is enormous.

P.P.P.S. By contrast, the evidence is very clear that higher taxes actually make debt problems worse.

———

Image credit: pxhere | CC0 Public Domain.