Let’s look today at one of main arguments for Biden’s tax-and-spend agenda.

A column in the New York Times, authored by Spencer Bokat-Lindell, suggests that the United States needs to increase government spending on child care to “shrink the gap” with other nations.

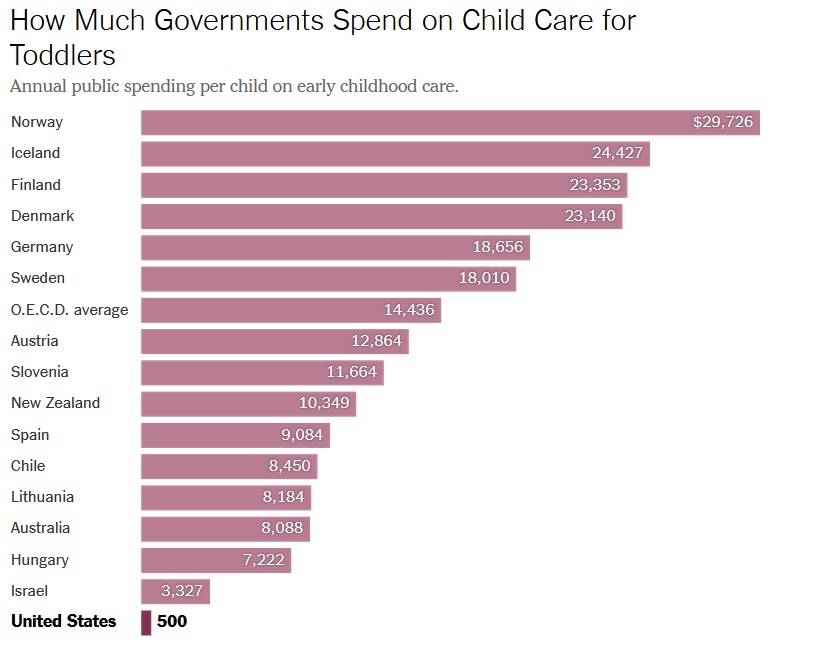

The main evidence for this proposition is a chart showing the United States at the bottom.

The obvious goal is to convince readers that the United States is doing something wrong.

And that comes across in the text of the article.

If you’re active on social media there’s a decent chance you came across this chart…about how much less the U.S. government spends on young children’s care than other rich countries. The infrastructure and family plan that President Biden proposed and that’s now being negotiated in Congress is an attempt to shrink the gap through four key policies: a federal paid family and medical leave program, an extension of the child tax credit (in the form of a monthly payment) that debuted this year, subsidized day care, and universal pre-K.

But why is it bad to be at the bottom of this list when all the nations above the U.S. have lower living standards?

I’ve repeatedly made the point that we don’t want to “catch up” to nations that have lower levels of prosperity.

- Household consumption is 50 percent higher in the United States than the average of other developed nations.

- The bottom 20 percent of Americans have higher living standards than the average European

- The bottom 10 percent of Americans enjoy better lives than the average citizens of OECD nations.

But maybe this isn’t just about living standards.

The article also suggests that childcare subsidies are needed to avert demographic decline.

…Why does the United States have such an exceptional approach to family and child care benefits…? European and Latin American countries began enacting these policies…the end of World War II accelerated the process, particularly in Europe… “Part of it had to do with fears of demographic decline…the need to recover from those years and to ensure that there was a strong work force going forward,” Siegel told the BBC.

For what it’s worth, I agree that demographic decline is a major issue.

Falling birth rates and increased life expectancy are a very worrisome combination for government budgets.

Which leads to the hypothesis that childcare subsidies can help deal with this problem by enabling higher levels of fertility.

That’s theoretically possible, I’ll admit, but we certainly don’t see it in the data. Here’s the chart from the New York Times, which I’ve augmented by showing fertility rates.

As you can see, the United States has a higher fertility rate than almost every other nation on the list, which certainly suggests that childcare subsidies are not an effective way of encouraging more babies.

Moreover, U.S. fertility of 1.71 is higher than the OECD average of 1.61.

And when you compare the United States to peer nations (“OECD rich nations” and “EU-15 nations”), the fertility gap is even larger, 1.71 to 1.52.

One moral of the story is that government handouts are not an effective way of increasing fertility.

And the other moral of the story is that it’s not a good idea to copy nations that are economically weaker.

———

Image credit: Fort George G. Meade Public Affairs Office | CC BY 2.0.