Public finance theory teaches us that the capital gains tax should not exist. Such a levy exacerbates the bias against saving and investment, which reduces innovation, hinders economic growth, and lowers worker compensation.

All of which helps to explain why President Biden’s proposals to increase the tax burden on capital gains are so misguided.

- He wants a radical increase in the tax rate on capital gains – from 23.8 percent to 43.4 percent, the highest burden in the world.

- He wants to impose capital gains tax on assets when people die, even if assets aren’t sold and there are not any actual capital gains.

Thanks to some new research from Professor John Diamond of Rice University, we can now quantify the likely damage if Biden’s proposals get enacted.

Here’s some of what he wrote in his new study.

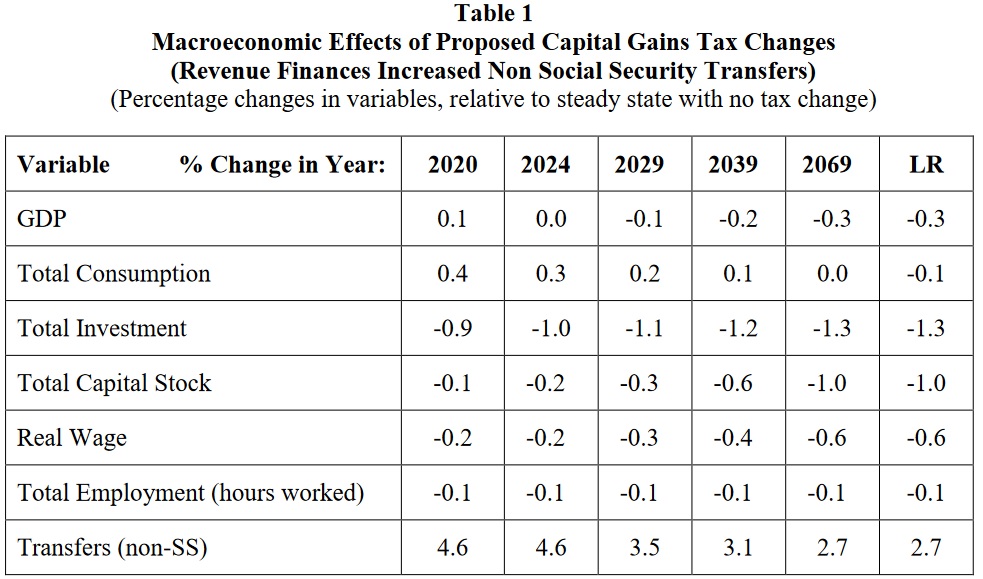

We use a computable general equilibrium model of the U.S. economy to simulate the economic effects of these policy changes… The model is a dynamic, overlapping generations, computable general equilibrium model of the U.S. economy that focuses on the macroeconomic and transitional effects of tax reforms. …The simulation results in Table 1 show that GDP falls by roughly 0.1 percent 10 years after reform and 0.3 percent 50 years after reform, which implies per household income declines by roughly $310 after 10 years and $1,200 after 50 years. The long run decline in GDP is due to a decline in the capital stock of 1.0 percent and a decline in total hours worked of 0.1 percent. …this would be roughly equivalent to a loss of approximately 209,000 jobs in that year. Real wages decrease initially by 0.2 percent and by 0.6 percent in the long run.

Here is a summary of the probable economic consequences of Biden’s class-warfare scheme.

But the above analysis should probably be considered a best-case scenario.

Why? Because the capital gains tax is not indexed for inflation, which means investors can wind up paying much higher effective tax rates if prices are increasing.

And in a world of Keynesian monetary policy, that’s a very real threat.

So Prof. Diamond also analyzes the impact of inflation.

…capital gains are not adjusted for inflation and thus much of the taxable gains are not reflective of a real increase in wealth. Taxing nominal gains will reduce the after-tax rate of return and lead to less investment, especially in periods of higher inflation. …taxing the nominal value will reduce the real rate of return on investment, and may do so by enough to result in negative rates of return in periods of moderate to high inflation. Lower real rates of return reduce investment, the size of the capital stock, productivity, growth in wage rates, and labor supply. …Accounting for inflation in the model would exacerbate other existing distortions… An increase in the capital gains tax rate or repealing step up of basis will make investments in owner-occupied housing more attractive relative to other corporate and non-corporate investments.

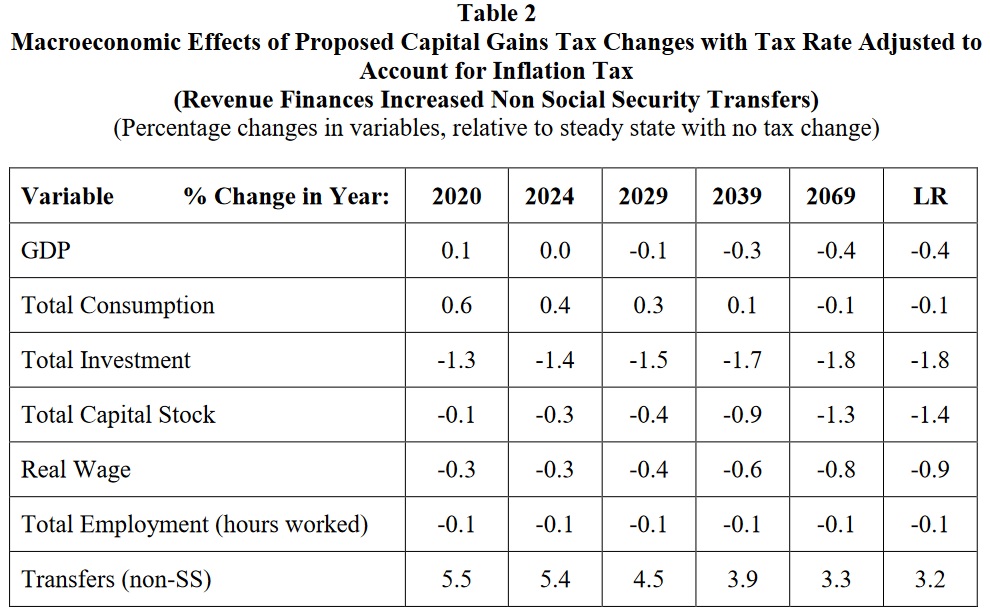

Here’s what happens to the estimates of economic damage in a world with higher inflation?

Assuming the inflation rate is one percentage point higher on average (3.2 percent instead of 2.2 percent) implies that a rough estimate of the capital gains tax rate on nominal plus real returns would be 1.5 times higher than the real increase in the capital gains tax rate used in the standard model with no inflation. Table 2 shows the results of adjusting the capital gains tax rates by a factor of 1.5 to account for the effects of inflation. In this case, GDP falls by roughly 0.1 percent 10 years after reform and 0.4 percent 50 years after reform, which implies per household income declines by roughly $453 after 10 years and $1,700 after 50 years.

Here’s the table showing the additional economic damage. As you can see, the harm is much greater.

I’ll conclude with two comments.

- First, inflation is obviously bad for citizens. But as I wrote more than 10 years ago, it’s profitable for governments.

- Second, even seemingly small differences in economic growth produce big differences in long-run living standards.

P.S. If (already-taxed) corporate profits are distributed to shareholders, there’s a second layer of tax on those dividends. If the money is instead used to expand the business, it presumably will increase the value of shares (a capital gain) because of an expectation of higher future income (which will be double taxed when it occurs).

———

Image credit: Max Pixel | CC0 Public Domain.