I’ve written about some boring and arcane tax issues – most of which are only relevant because we don’t have a simple and fair flat tax.

- Depreciation vs. expensing

- Territorial taxation vs. worldwide taxation

- GILTI rules for multinational firms

- Carry-forwards and net-operating losses

- Tax treatment of debt and equity

But I always try to explain why these complicated tax issues are important – assuming we want a competitive tax system that doesn’t needlessly undermine growth.

Today, we’re going to add to our collection of nerdy tax topics by discussing the issue of “book income” vs “tax income.”

I’m motivated to address this topic because the oleaginous senior senator from Massachusetts, Elizabeth Warren, indirectly addressed this issue in a recent column for the Washington Post.

Here’s some of what she wrote.

…scores of giant U.S. corporations pay zero. …In the three years following the 2017 Republican tax cuts, 39 megacorporations, including Amazon and FedEx, reported more than $122 billion in profits to their shareholders while using loopholes, deductions and exemptions to pay zero in federal income taxes. These companies boosted their stock prices and increased CEO pay by telling their shareholders they raked in hundreds of millions of dollars in profits, while simultaneously telling the Internal Revenue Service that they don’t owe any taxes. …We would require any company that earns more than $100 million in profits to pay a 7 percent tax on every dollar earned above that amount.

To assess Warren’s proposal, here are a couple of things that you need to understand.

- What corporations report to their shareholders is “book income,” and that number is governed by a specific set of rules (“generally accepted accounting principles” or GAAP) determined by the Financial Accounting Standards Board. The goal is to make sure investors and others have accurate information.

- What companies report to the Internal Revenue Service is “tax income” and that number is governed by a specific set of laws (the tax code) enacted over the past 100-plus years by politicians.

In other words, companies are not choosing to play games. They have no choice. They are following two separate sets of requirements that were set up for two separate reasons.

For purposes of public policy, the key thing to understand is that the tax code is based largely on cash flow (what was taxable income over the past 12 months, for instance).

That means it produces annual numbers that can be quite different than book income’s long-run data based on accrual accounting (the GAAP rules).

The Tax Foundation has a recent report, authored by Erica York and Alex Muresianu, that shows why it would be a major mistake to use book income for tax purposes.

Under corporate book income rules, companies spread out the cost of investments across roughly its useful life, also known as economic depreciation. The purpose of this rule is to match costs to the revenues they generate to best inform creditors and shareholders: deducting, say, the entire cost of a new factory the year it’s constructed could make it seem like a company is unprofitable to shareholders. While the economic depreciation approach makes some sense for accounting purposes, it’s a bad framework for tax policy. Spreading out the deductions over time creates a tax bias against investment. Deductions in future years are worth less than deductions in the current year, thanks to the time value of money and inflation. It also creates a bias against companies that rely heavily on physical capital (think energy production and high-tech manufacturing), and towards companies that mostly rely on labor (think financial services or fast food).

It’s unclear whether Senator Warren (or her staff) actually understand these technical details.

Not that it really matters. Her goal is to play class warfare. She’s engaging in demagoguery (a long-standing pattern) in hopes of enacting legislation that will give her a lot more money to spend.

If she’s successful, it will be very bad news for the economy, as Kyle Pomerleau explained in a 2019 report for the Tax Foundation.

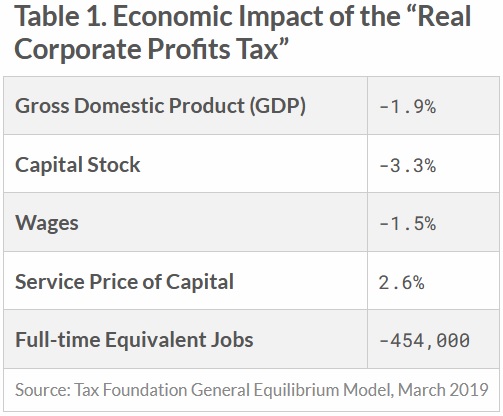

According to the Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, this proposal would reduce economic output (GDP) by 1.9 percent in the long run. We also estimate that the capital stock would be 3.3 percent smaller and wages 1.5 percent lower, with about 454,000 fewer full-time equivalent jobs. …We estimate that the service price would rise by 2.6 percent under this proposal. A higher service price means that capital investment would become less attractive, leading to reduced investment and, eventually, a smaller capital stock. The smaller capital stock would lead to lower output, lower worker productivity, and lower wages. …Taxpayers in the bottom four income quintiles…would see a reduction in after-tax income of between 1.64 percent and 1.95 percent.

And here’s a table from Kyle’s report with all the economic consequences.

P.S. In her column, Sen. Warren also reiterated her support for a destructive wealth tax and more funding to reward a corrupt IRS.

———

Image credit: Gage Skidmore | CC BY-SA 2.0.