While it’s true that every penny in the budget requires money to be diverted from the economy’s productive sector, not all government spending is created equal when considering the impact on growth.

Some types of spending, such as redistribution programs, are doubly harmful to prosperity. The economy is first hurt by the taxes needed to finance the programs, and then the economy is hurt because the programs give people incentives to rely on the government rather than work.

Other types of spending, however, require a cost-benefit analysis.

Consider the case of education. There are costs when politicians take money out of the private sector to finance education, but there are benefits from having an educated population.

That doesn’t tell us how much to spend, of course, and it also overlooks equally important questions such as whether the money will generate better results if used to finance a government monopoly or a choice-based system. But I’m simply making the point that there are costs and benefits.

Now let’s apply this analysis to government-financed research and development, which involves everything from the National Science Foundation to NASA, and from global warming grants to weapons development for the Pentagon.

Proponents argue that these are “public goods,” meaning that they produce economy-wide benefits and can only be handled by government.

But that view seems to be based in large part on faith rather than evidence.

Matt Ridley, the former science editor for the Economist, wrote about this topic for the Wall Street Journal back in 2015. If you only have time to read one article, this might be the best choice.

He starts by explaining that most breakthroughs come from private initiative.

Most technological breakthroughs come from technologists tinkering, not from researchers chasing hypotheses. Heretical as it may sound, “basic science” isn’t nearly as productive of new inventions as we tend to think. …Politicians believe that innovation can be turned on and off like a tap: You start with pure scientific insights, which then get translated into applied science, which in turn become useful technology. So what you must do, as a patriotic legislator, is to ensure that there is a ready supply of money to scientists on the top floor of their ivory towers, and lo and behold, technology will come clanking out of the pipe at the bottom of the tower. …this story…so prevalent in the world of science and politics—that science drives innovation, which drives commerce—is mostly wrong. It misunderstands where innovation comes from. Indeed, it generally gets it backward. …It is no accident that astronomy blossomed in the wake of the age of exploration. The steam engine owed almost nothing to the science of thermodynamics, but the science of thermodynamics owed almost everything to the steam engine. …Technological advances are driven by practical men who tinkered until they had better machines; abstract scientific rumination is the last thing they do.

Government funding, by contrast, does not have a good track record.

It follows that there is less need for government to fund science: Industry will do this itself. Having made innovations, it will then pay for research into the principles behind them. Having invented the steam engine, it will pay for thermodynamics. …For more than a half century, it has been an article of faith that science would not get funded if government did not do it, and economic growth would not happen if science did not get funded by the taxpayer. …there is still no empirical demonstration of the need for public funding of research and that the historical record suggests the opposite. After all, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. and Britain made huge contributions to science with negligible public funding, while Germany and France, with hefty public funding, achieved no greater results either in science or in economics. …public funding of research almost certainly crowds out private funding. That is to say, if the government spends money on the wrong kind of science, it tends to stop researchers from working on the right kind of science.

Ridley doesn’t claim there are no benefits. Instead, he makes the more practical point that government R&D has high costs with relatively low benefits.

…the argument for public funding of science rests on a list of the discoveries made with public funds, from the Internet (defense science in the U.S.) to the Higgs boson (particle physics at CERN in Switzerland). But that is highly misleading. Given that government has funded science munificently from its huge tax take, it would be odd if it had not found out something. This tells us nothing about what would have been discovered by alternative funding arrangements. And we can never know what discoveries were not made because government funding crowded out philanthropic and commercial funding.

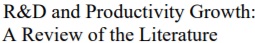

Ridley’s analysis is backed up by scholarly research.

Here are some excerpts from a study by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This paper reviews the literature on R&D to provide guidelines for recent efforts to include R&D in the national income accounts. …The overall rate of return to R&D is very large, perhaps 25 percent as a private return and a total of 65 percent for social returns. However, these returns apply only to privately financed R&D in industry. Returns to many forms of publicly financed R&D are near zero. …On the basis of the evidence considered, privately financed R&D in industry should be treated as an investment and included in the relevant R&D stock. Returns to R&D are very high, but these high returns accrue only to privately financed R&D. Many elements of university and government research have very low returns, overwhelmingly contribute to economic growth only indirectly, if at all, and do not belong in investment.

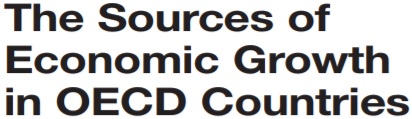

And here are some passages from a 2003 report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

…the pace of accumulation of physical and human capital plays a major role in the growth process. Most notably, the estimated impact of increases in human capital (as measured by average years in education) on output suggests high returns to investment in education. The results also point to a marked positive effect of business-sector R&D, while the analysis could find no clear-cut relationship between public R&D activities and growth …there are significant differences in the returns of R&D expenditure across sectors, and the private sector may be better able to channel resources towards high return R&D activities …regressions including separate variables for business-performed R&D and that performed by other institutions (mainly public research institutes) suggest that it is the former that drives the positive association between total R&D intensity and output growth. …The negative results for public R&D are surprising…they suggest publicly-performed R&D crowds out resources that could be alternatively used by the private sector, including private R&D. There is some evidence of this effect in studies.

Terence Kealey’s 2017 testimony to the Senate’s Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee also is worth perusing.

…the British Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, like the British Agricultural Revolution of the 18th century, was laissez faire… The US was laissez faire in science between 1776 and 1940, yet by 1890 it had overtaken the UK to become the richest industrialized country in the world. Meanwhile those European countries – including France and the German states – whose governments invested most in science failed to converge on the UK or the US, let alone overtake them. …as shown by the successes of the Wright brothers, Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, to say nothing of the great industries of Pittsburgh and Detroit – US science, technology and industry flourished. …since 1830 the long-term rates of GDP per capita and TFP (total factor productivity) growth in the US have been steady (with GDP per capita, for example, growing at just under 2% per annum) and the inauguration of the federal funding for science had the following effect on long-term rates of GDP per capita and TFP growth: none.

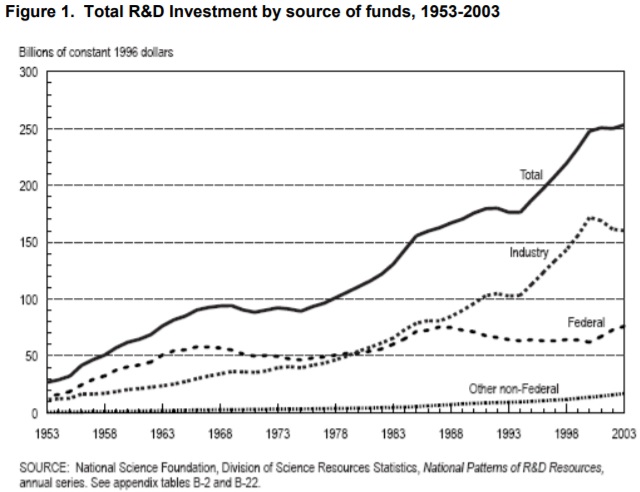

The good news, relatively speaking, is that the private sector now plays a very dominant role in R&D expenditures.

This was not always the case. This chart, from Iain Murray’s research, shows that government played the dominant role in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

Let’s close with two real-world examples of how private R&D drives progress.

First, here are some excerpts from a 2017 column in the Wall Street Journal by Tom Stossel.

He explains that progress in curing and treating diseases comes from the private sector rather than the National Institutes of Health.

The assumption seems to be that the root of all medical innovation is university research, primarily funded by federal grants. This is mistaken. The private economy, not the government, actually discovers and develops most of the insights and products that advance health. The history of medical progress supports this conclusion. …innovation came from physicians in universities and research institutes that were supported by philanthropy. Private industry provided chemicals used in the studies and then manufactured therapies on a mass scale. …Practical innovation requires incremental efforts. But the reviewers of grant applications for medical research are obsessed with theory-based science and novelty for novelty’s sake. …Academic administrators, operating under the delusion that government largess would grow forever, have become entitled. …By contrast, private investment in medicine has kept pace with the aging population and is the principal engine for advancement. More than 80% of new drug approvals originate from work solely performed in private companies. …Great advances in health care have been made, but there are still important challenges, from obesity to dementia. One step toward addressing them would be for Washington to adopt the right approach to medical innovation—and to stop simply throwing money at the current inefficient system.

Second, here’s more of Terence Kealey’s work, in this case some commentary from last year that focuses on space exploration.

…all powered flight started in the private sector, for the Wright brothers were not government‐funded researchers. …A team of full‐time government‐funded researchers, operating out of the Smithsonian Institution, were then also trying to launch heavier‐than‐air machines. Even though the Smithsonian team enjoyed a budget that was a hundred times larger than that of the Wrights, its prototypes always crashed. Airplanes are but one of the many gifts that private research and development has bestowed on humanity. As are space rockets. The great space‐rocket pioneer was Robert “Moonie” Goddard (1882–1945), a professor at Clark College in Massachusetts. Funded with $100,000 from the Guggenheims and $10,000 from the Hodgkins Fund, the projects that resulted in his achievements were extraordinary: By 1925 he had created the first liquid‐fueled rocket. By 1932 he had developed a gyro stabilizer… Elon Musk’s company, SpaceX,…doing something — namely, putting humans into orbit — that previously had been achieved only by governments. NASA could now be seen as only a temporary interruption of a process that had started in the private sector. …If there is a science that proves the resilience of the private sector, it is space science, including, of course, astronomy. Time again, what at the time was the largest optical telescope in the world was privately funded… Radio astronomy, moreover, was actually born in the private sector, when Karl Jansky of Bell Labs discovered in 1931 that stars emitted radio waves. Grote Reber, a radio engineer, built the first radio telescope, a parabolic dish reflector in his backyard in Chicago in 1937.

The purpose of this column isn’t to argue that there shouldn’t be any government-funded research.

Indeed, because there’s at least some hope of that such spending generates benefits, I prefer R&D spending over almost all other types of spending (it’s better than redistribution outlays, and also better than money that goes for the Department of Agriculture, Department of Education, Department of Housing and Urban Development, etc).

But “better than” other types of government spending is not the same as “better than” leaving the money in the economy’s productive sector.

The bottom line is that there simply isn’t any evidence that government-financed R&D generally passes the cost-benefit test described at the start of the column.

Which means that we should be very skeptical when politicians and interest groups plead for more funding (needless to say, evidence tells us we should be skeptical of any requests for bigger government, not just those for more R&D spending).