In the world of public finance, Ireland is best known for its 12.5 percent corporate tax rate.

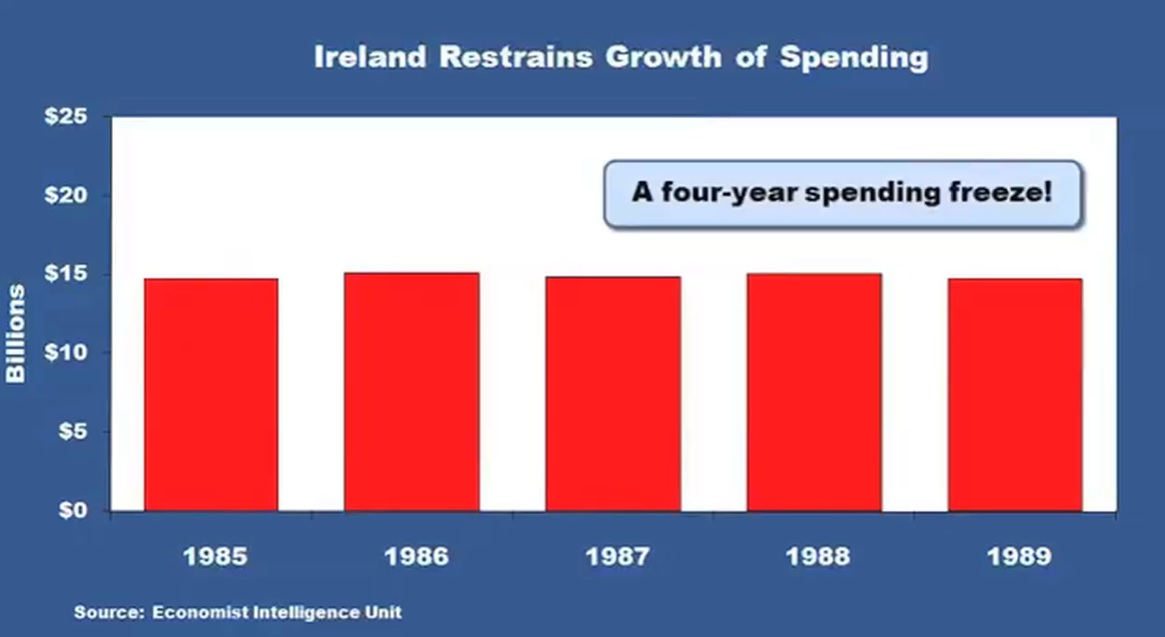

That’s a very admirable policy, as will be momentarily discussed, but my favorite Irish policy was the four-year spending freeze in the late 1980s.

I discussed that fiscal reform in a video about 10 years ago, and I subsequently shared data on how spending restraint reduced the overall burden of government in Ireland and also lowered red ink.

It’s a great case study showing the beneficial impact of my Golden Rule.

Spending restraint also paved the way for better tax policy, and that’s a perfect excuse to discuss Ireland’s pro-growth corporate tax system. The Wall Street Journal opined last week about that successful supply-side experiment.

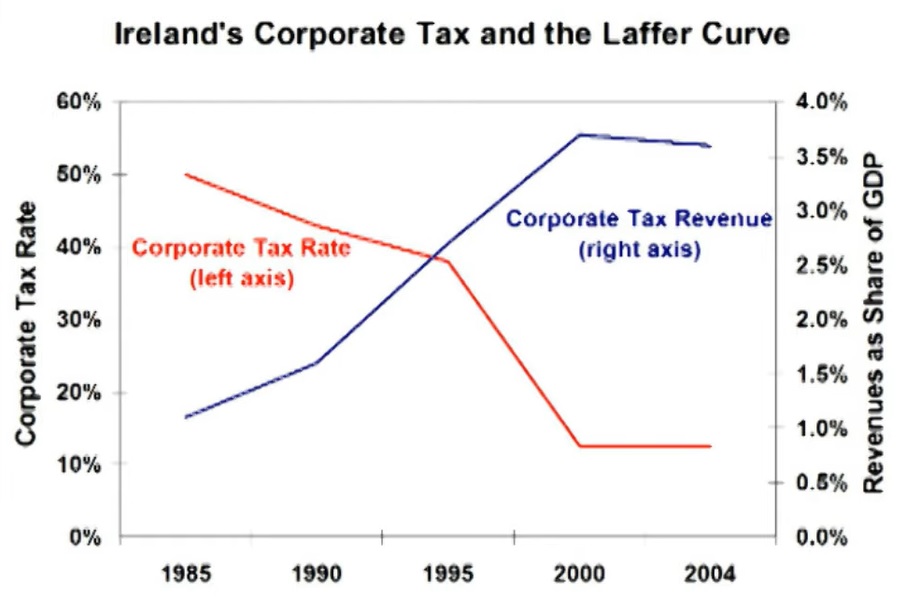

Democrats want a high global minimum tax that would end national tax competition and reduce the harm from their huge tax increase on U.S. business. But tax competition has been a boon to global growth and investment, as Ireland’s famous low-tax policy makes clear. Far from a “race to the bottom,” Ireland adopted policies that were ahead of their time and helped its economy grow from a backwater into a Celtic tiger. …in the late 1990s …an EU mandate led Dublin to…pioneer…a new strategy: Apply the same low tax rate to every business. Policy makers settled on 12.5%, which was a tax increase for some companies but a cut for others. This was a classic flat-tax reform… Ireland has reaped the benefits. Between 1986 and 2006, the economy grew to nearly 140% of the EU average from a mere two-thirds. Employment nearly doubled to two million, and the brain drain of the 1970s and 1980s reversed. …Oh and by the way: After Ireland slashed its rate and broadened the corporate-tax base, tax revenue soared. Except for the post-2008 recession and its aftermath, corporate-profits taxes in some years account for about 13% of total revenue and exceed 3% of GDP. That’s up from as low as 5% of revenue and less than 2% of GDP before the current tax rate was introduced.

That’s a lot of great information, particularly the last couple of sentences about how Ireland collected more revenue when the corporate tax rate was slashed.

Indeed, I discussed that remarkable development in Part II of my video series on the Laffer Curve (and it’s not just an Irish phenomenon since both the IMF and OECD have persuasive global data on lower corporate tax rates and revenue feedback).

Though higher revenue is not necessarily a good thing.

I complained back in 2011, for example, about how Irish politicians began to spend too much money once a booming economy began to generate a lot of tax revenue.

Which is a good argument for a Swiss-style spending cap in Ireland.

Let’s wrap up by considering some fiscal lessons from Ireland. Here are four things everyone should know.

- Spending restraint is a powerful tool to achieve smaller government..

- Lower tax rates on productive behavior lead to jobs and prosperity.

- Lower corporate tax rates can generate substantial revenue feedback.

- A spending cap is needed to maintain long-run fiscal discipline.

Good rules for Ireland. Good rules for any nation.

P.S. Ireland has definitely prospered in recent decades, but GNI data gives a more accurate picture than GDP data.

———

Image credit: Joe King | CC BY-SA 3.0.