I was a big fan of federalism (to the extent it still exists) before any of us ever heard of the coronavirus.

And, given the federal government’s incompetent response to the pandemic, I’m an even bigger fan of federalism today.

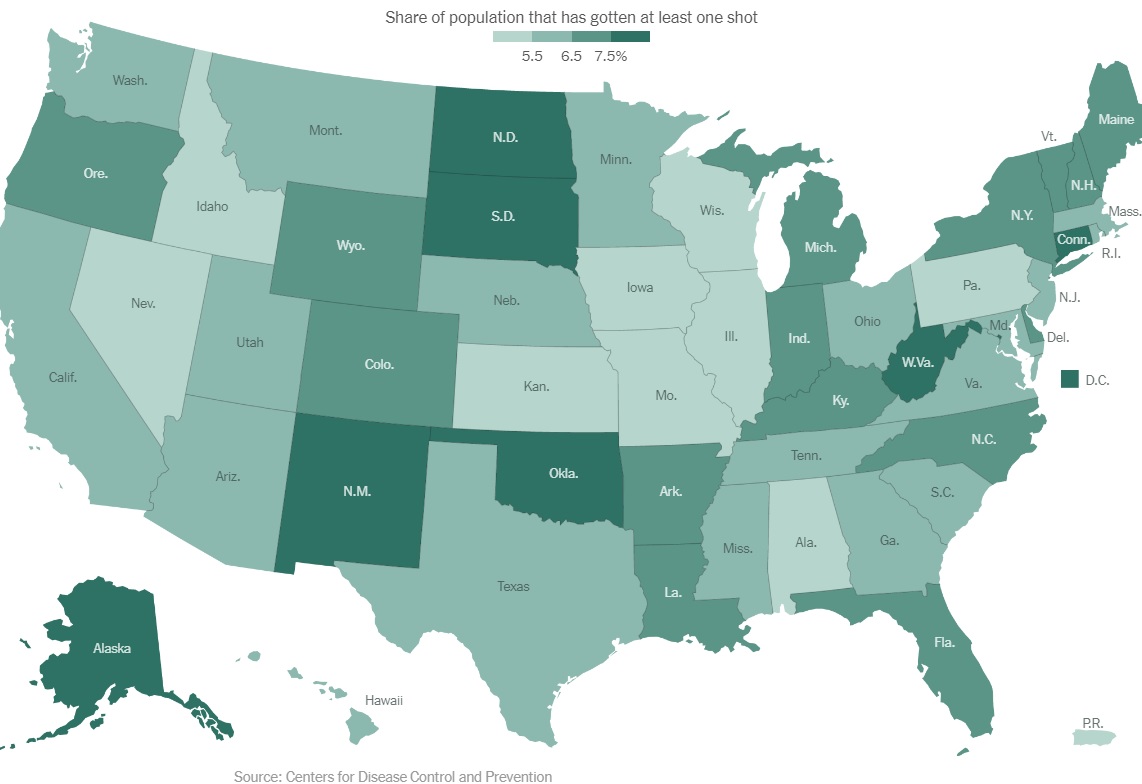

Though that doesn’t mean states are paragons of efficiency and competence. Here’s a map from the New York Times showing the percent of each state’s population that has receive at least one shot of the vaccine.

Why is Oklahoma doing so much better than Kansas? Why is West Virginia so far ahead of Pennsylvania?

Part of the answer is whether the states were willing to let Washington micro-manage their delivery.

The Wall Street Journal editorialized a few days ago about lessons we should learn.

The gap continues to grow between states that are getting shots into arms, and those arguing over who gets what and when. North Dakota had administered some 84% of its supply as of Jan. 23, and West Virginia about 83%—far better than states like California (45%) or Alabama (47%). Federalism is showing what works—and what doesn’t. …The risk is that Team Biden tries to micromanage state administration of the vaccine, especially now that the media, Democrats and some public-health officials are blaming slow state rollouts on a “vacuum” of federal leadership. But vaccine administration was always intended to be state-led, and too many jurisdictions squandered the ample time they had for preparation. …the biggest state mistakes so far have been adhering too much to the federal government’s initial guidance… The states with the highest per capita vaccination rates are all rule-breakers—Alaska (12,885 per 100,000), West Virginia (11,321), and North Dakota (9,602) as of Jan. 23. Top performers also thought creatively about how best to distribute and administer the vaccine, even if that meant departing from federal advice. …Mr. Biden is under pressure from the left to infuse the vaccine rollout with “equity” politics. As California (5,568 per 100,000) and New York (5,816 per 100,000) show, such bickering is a recipe for fewer vaccines and more deaths.

George Will, opining in today’s Washington Post, adds his two cents to the discussion, citing Philip Howard’s work on inflexible bureaucracy.

The covid-19 tragedy teaches this: Government is more apt to achieve adequacy when it does not try to achieve purity. …the benefits of federalism: Among 50 governors, at least a few are apt to be wiser and nimbler than the federal bureaucracy. …there are too many lawyers and too much law, and that both surpluses are encouraged by misbegotten ideas about ideal governance. “…This is not an unavoidable side-effect of big government, but a deliberate precept of its operating philosophy. Law will not only set goals and governing principles, but it will also dictate exactly how to implement those goals correctly.” …Then the pandemic arrived. Red tape prevented public health officials from using tests they possessed or buying tests overseas. To function, hospitals had to jettison myriad dictates about restrictions on telemedicine, ambulance equipment and many other matters. …The Progressive Era project that began 120 years ago got its second wind 60 years ago. …A virulent, fast-moving and mutating virus is teaching the cost of this.

Normally, I would argue against any government involvement.

In this case, however, taxpayers financed a big chunk of the development, so I’ll begrudgingly acknowledge that this gives politicians and bureaucrats the right to make allocation decisions.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t criticize those decisions when they result in mistakes. Especially since delayed vaccine rollout literally can result in needless deaths.

There are no perfect answers in this kind of situation, but surely we would be in better shape if Washington simply distributed the vaccines to the states, with the assumption that they would immunize as many people as possible, as quickly as possible.

Yes, some states would bungle the process (as we’re seeing in poorly governed jurisdictions such as New York and California), but a big advantage of federalism is that residents might learn from the superior performance of other states that they need better-quality elected officials.

Federalism was the right way of deciding lockdown policies, and it’s the right way of determining vaccination policies.

P.S. In his column, George Will cites Philip Howard, who thinks bureaucratic rules from Washington are too rigid. I certainly agree that a prescriptive, one-size-fits-all approach is misguided, but regulatory flexibility can be a recipe for corruption and cronyism. The right approach is to end federal involvement whenever possible.

———

Image credit: Shaw Girl | CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.